Adventures of William Tell

Plot

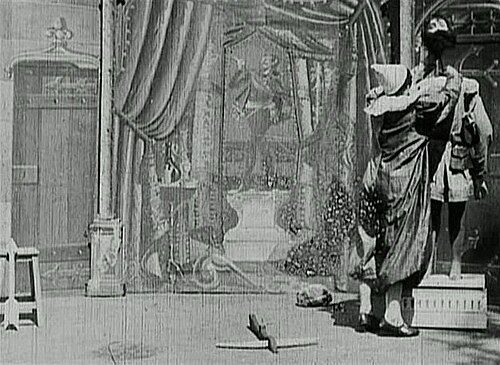

The film opens in an artist's studio where an unfinished statue of the legendary Swiss hero William Tell stands on a pedestal. A clown character enters the scene and proceeds to complete the statue by attaching clay arms and a head to the existing form. To secure the head in place, he places a heavy brick on top. When the clown turns his back, the statue miraculously comes to life, transforming into a living, breathing representation of William Tell. The animated statue then begins to move and interact with the clown, creating a magical and comedic sequence that showcases Méliès' pioneering special effects techniques. The film concludes with further fantastical transformations and magical occurrences typical of Méliès' work.

Director

About the Production

Filmed in Georges Méliès' personal glass studio in Montreuil, which was specially designed with a glass roof to maximize natural lighting for early film production. The film was created using Méliès' innovative substitution splicing technique and multiple exposures to create the magical transformation effects. As with many of Méliès' films from this period, it was hand-colored frame by frame for certain releases, a labor-intensive process that added vibrant colors to the black and white footage.

Historical Background

1898 was a pivotal year in early cinema, occurring just three years after the Lumière brothers' first public film screening. The film industry was still in its infancy, with most films being simple actualities or brief trick films. Méliès was one of the few filmmakers creating narrative fiction with magical elements. This period saw the rise of cinema as both a technological novelty and an art form. The late 1890s also coincided with the peak of European colonial expansion and the Belle Époque era in France, a time of artistic innovation and cultural optimism. The choice of William Tell as a subject reflected the 19th-century romantic nationalism that was prevalent throughout Europe.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents an important milestone in the development of cinematic language and special effects. Méliès' work, including this film, helped establish cinema as a medium for fantasy and storytelling rather than just documentary. The film demonstrates early narrative structure and character development in a medium that was previously dominated by simple actualities. Méliès' techniques influenced generations of filmmakers and established many conventions of special effects that would be refined over the coming century. The film also exemplifies the transition from stage magic to cinematic magic, showing how the new medium could create illusions impossible in live theater.

Making Of

Georges Méliès, a former magician and theater owner, brought his stage magic expertise to the new medium of cinema. The film was shot in his custom-built studio, which featured elaborate painted backdrops and theatrical props. Méliès would have used his patented multiple exposure technique to create the statue transformation effect, carefully stopping the camera, replacing the prop statue with an actor, then restarting filming. The hand-coloring process, when used, was done by Méliès' team of women colorists who would meticulously paint each frame by hand. The clown character's movements were deliberately exaggerated to ensure visibility in the early film format and to enhance the comedic effect.

Visual Style

The film utilizes Méliès' characteristic theatrical cinematography style, with a single static camera positioned to capture the entire scene as if it were a stage performance. The lighting was natural, coming through the glass roof of Méliès' studio. The visual composition follows theatrical conventions with clear foreground and background separation. The camera work is straightforward, focusing attention on the magical transformations rather than camera movement. The hand-colored versions featured vibrant, flat colors typical of early film coloring techniques.

Innovations

The film showcases Méliès' pioneering use of substitution splicing, where he would stop the camera, make changes to the scene, then resume filming to create the illusion of magical transformation. This technique, which Méliès accidentally discovered and then perfected, became a cornerstone of early special effects. The film also demonstrates early use of multiple exposure to create ghostly or magical appearances. The hand-coloring process, while not invented by Méliès, was perfected in his studio and represented a significant technical achievement in early cinema, requiring hundreds of hours of meticulous work for a single short film.

Music

As a silent film from 1898, there was no synchronized soundtrack. The film would have been accompanied by live music during exhibition, typically a pianist or small orchestra playing appropriate music. The choice of music would have been left to the individual exhibitor, ranging from popular tunes of the era to classical pieces. In some venues, sound effects might have been created live to enhance the magical moments, such as bells or chimes during the transformation sequence.

Famous Quotes

No dialogue - silent film era

Memorable Scenes

- The magical transformation of the clay statue into a living William Tell, achieved through Méliès' pioneering substitution splicing technique, creating one of cinema's earliest examples of bringing inanimate objects to life through special effects

Did You Know?

- This film was released as Star Film Company catalog number 167

- The film showcases Méliès' pioneering use of the substitution splice technique, which he invented and perfected

- William Tell was a popular cultural figure in the 19th century, symbolizing resistance against oppression

- The film was part of Méliès' series of magical transformation films that helped establish cinema as a medium for fantasy

- Like many early Méliès films, it was sold both in black and white and hand-colored versions

- The clown character was likely played by Méliès himself, as he often performed in his own films

- This film was created during the peak of Méliès' most productive period (1897-1902)

- The film was distributed internationally, including in the United States through the Edison Manufacturing Company

- The statue transformation effect was achieved through careful editing and multiple exposure techniques

- This film represents Méliès' fascination with bringing inanimate objects to life, a recurring theme in his work

What Critics Said

Contemporary reception of Méliès' films was generally positive, with audiences marveling at the magical effects and transformations. Trade publications of the era praised his inventive use of the new medium. Modern film historians and critics recognize 'Adventures of William Tell' as an important example of early cinematic storytelling and special effects innovation. The film is often cited in scholarly works about Méliès' contributions to cinema and the development of visual effects. Critics today appreciate the film's historical significance and its role in establishing cinema as a medium for fantasy and imagination.

What Audiences Thought

Late 19th-century audiences were fascinated by Méliès' magical films, which offered a stark contrast to the simple actualities being produced by other filmmakers. The transformation effects in 'Adventures of William Tell' would have been seen as genuinely magical to viewers of the time, many of whom had never witnessed moving images before. The film's combination of comedy, magic, and the familiar legend of William Tell made it popular with diverse audiences. Méliès' films were commercial successes both in France and internationally, helping establish him as one of the first true film directors and entrepreneurs.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage magic and illusion shows

- Theatrical performances

- Folklore and legends

- Commedia dell'arte

This Film Influenced

- Later Méliès trick films

- Early fantasy and horror films

- Animation films featuring inanimate objects coming to life

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives and is preserved in film archives. Copies are held by major film institutions including the Cinémathèque Française. The film has been restored and digitized as part of various Méliès film collections. Both black and white and hand-colored versions may exist, though the hand-colored versions are rarer due to the labor-intensive nature of the coloring process.