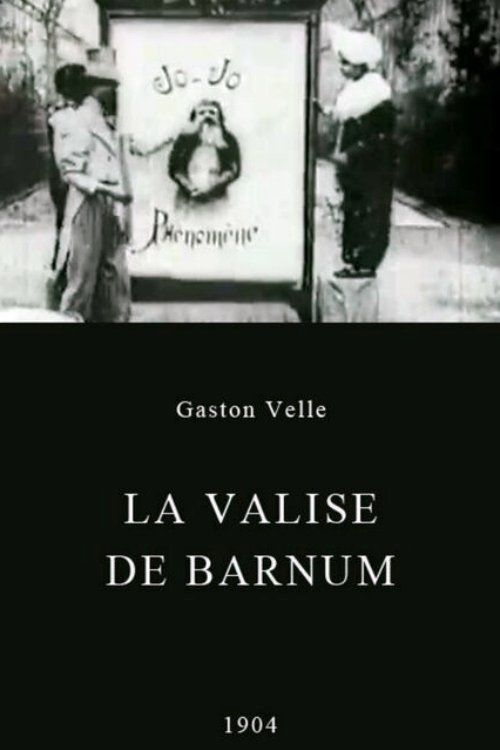

Barnum's Trunk

Plot

In this early French trick film, a magician and his assistants set up a large frame on stage and proceed to hang various music hall posters within it. Using magical powers, the magician brings each poster to life one by one, transforming the static images into living, breathing performers. The posters depict various acts including dancers, acrobats, and other entertainers who emerge from their two-dimensional confines to perform for the audience. Each transformation showcases the magical possibilities of cinema itself, with performers literally jumping off the page and into reality before eventually returning to their poster form. The film concludes with the magician taking a final bow, having demonstrated his power over both illusion and the medium of film.

Director

Cast

About the Production

Barnum's Trunk was created during the golden age of French trick films, utilizing multiple exposure and substitution splicing techniques that were pioneered by Georges Méliès. Gaston Velle, himself a magician, brought his stage experience to the film, creating seamless transitions between the 2D posters and 3D performers. The film was shot in black and white but was likely hand-colored for certain releases, a common practice for Pathé productions of this era. The production required careful choreography to time the actors' appearances with the magical transformations.

Historical Background

1904 was a pivotal year in early cinema, with the medium transitioning from novelty to art form. The film emerged during the peak of French cinematic dominance, when Pathé Frères was the world's largest film production company. This period saw the development of narrative cinema and the refinement of special effects techniques. The film reflects the fascination with magic and illusion that characterized early cinema, as filmmakers sought to demonstrate the unique capabilities of the new medium. The reference to P.T. Barnum also indicates the growing transatlantic cultural exchange and the international appeal of entertainment and spectacle in the early 20th century.

Why This Film Matters

Barnum's Trunk represents an important milestone in the development of visual effects and magical realism in cinema. It exemplifies the transition from stage magic to cinematic illusion, showing how filmmakers were adapting traditional entertainment forms for the new medium. The film's meta-narrative quality—bringing 2D images to 3D life—serves as an early meditation on the power of cinema itself to animate the inanimate. It contributed to the established tradition of trick films that would influence generations of filmmakers and special effects artists. The work also demonstrates the international nature of early cinema, with French filmmakers drawing inspiration from American show business figures like P.T. Barnum.

Making Of

Gaston Velle brought his extensive background as a stage magician to this film, using his understanding of illusion and audience expectation to create compelling visual tricks. The production would have required precise timing and multiple takes to achieve the seamless transitions between posters and live performers. Velle likely used substitution splicing, where the camera would be stopped, the poster replaced with live actors, and filming resumed, creating the illusion of transformation. The hand-coloring process, if used, would have been done by women workers in the Pathé factory, using tiny brushes to color each frame individually. The film's simplicity belies the technical complexity involved in creating these early special effects, which were cutting-edge for their time.

Visual Style

The cinematography in Barnum's Trunk is characteristic of early cinema, with a fixed camera position and theatrical staging. The visual style emphasizes clarity and composition, ensuring that the magical transformations are clearly visible to the audience. The lighting would have been bright and even, typical of studio productions of the era, to facilitate the special effects work. The frame composition carefully balances the magical elements with the performers, creating a sense of wonder while maintaining visual coherence. Any hand-coloring would have added visual richness and helped distinguish between the magical and mundane elements of the narrative.

Innovations

Barnum's Trunk showcases several important technical achievements of early cinema, particularly in the realm of special effects. The film demonstrates sophisticated use of substitution splicing to create the illusion of posters coming to life. The seamless transitions between 2D and 3D elements required precise timing and technical skill. If hand-colored, the film represents the labor-intensive coloring techniques that added visual appeal to early films. The work also exemplifies the growing sophistication of narrative construction in early cinema, moving beyond simple actualities to create magical scenarios that could only exist on film.

Music

As a silent film, Barnum's Trunk would have been accompanied by live music during its original exhibition. The musical accompaniment likely consisted of popular tunes of the era or original compositions that matched the film's magical and whimsical tone. The music would have helped emphasize the moments of transformation and added to the overall sense of wonder. In modern screenings, the film is typically accompanied by period-appropriate music or newly composed scores that respect the film's historical context and magical themes.

Famous Quotes

No dialogue - silent film

Memorable Scenes

- The magical moment when the first poster transforms into a living performer, demonstrating the film's central premise and technical innovation

Did You Know?

- Gaston Velle was not only the director but also starred as the magician in the film, drawing from his real-life experience as a stage magician

- The film was distributed internationally under different titles, including 'Le Trunk de Barnum' in France and 'Barnum's Trunk' in English-speaking countries

- This film is part of a series of trick films Velle made for Pathé, often featuring magical transformations and illusions

- The title references P.T. Barnum, the famous American showman, though the film itself is purely French in origin and sensibility

- The technique of bringing posters to life was innovative for 1904 and demonstrated the magical possibilities of the new medium of cinema

- Like many films of this era, it was likely shown with live musical accompaniment, typically a pianist or small orchestra

- The film was hand-colored frame by frame for some releases, a laborious process that added significant visual appeal

- Velle worked previously with Georges Méliès, and the influence of Méliès' magical cinema style is evident in this work

- The film was shot on a single set with minimal camera movement, typical of early cinema but effective for the magical transformations

- This film survives today in film archives, though some versions may be incomplete or damaged

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews from 1904 are scarce, as film criticism was still in its infancy. However, trade publications of the time likely praised the film's technical innovations and entertainment value. Modern film historians recognize Barnum's Trunk as a significant example of early French trick cinema and an important work in Gaston Velle's oeuvre. Critics today appreciate the film for its sophisticated use of early special effects and its role in the development of cinematic language. The film is often cited in studies of early cinema and the evolution of visual effects techniques.

What Audiences Thought

Early 20th century audiences would have been delighted by the film's magical transformations, which represented cutting-edge entertainment for the time. The novelty of seeing static images come to life would have been particularly impressive to viewers unfamiliar with cinematic tricks. The film's brevity and clear visual storytelling made it accessible to international audiences, contributing to its wide distribution. Modern audiences viewing the film in archival contexts appreciate it as a historical artifact and a demonstration of early cinematic creativity, though the impact of the effects is inevitably less startling to contemporary viewers accustomed to computer-generated imagery.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Georges Méliès' trick films

- Stage magic traditions

- P.T. Barnum's circus and showmanship

- French theatrical traditions

This Film Influenced

- Later trick films by various directors

- Animated films featuring characters coming to life

- Modern films about the magic of cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in various film archives including the Cinémathèque Française and the Library of Congress. While complete versions exist, some prints may show signs of deterioration typical of films from this era. The film has been digitized as part of early cinema preservation efforts.