Billy Edwards and the Unknown

Plot

This early documentary short film captures a historic exhibition boxing match between Billy Edwards, a former lightweight champion who had transitioned to training and writing about the sport, and an unidentified challenger named Warwick. The carefully staged bout consists of five brief rounds, each lasting only 20 seconds, reflecting the technical limitations of early film equipment. Behind the boxing ring, a substantial crowd of onlookers has gathered, their presence adding to the spectacle and authenticity of the event. The film serves as both a sporting record and a demonstration of the new medium's ability to capture live action, showcasing the dynamic movements of the boxers and the atmosphere of a 19th-century sporting exhibition.

Director

Cast

About the Production

Filmed in Edison's innovative Black Maria studio, which featured a retractable roof to maximize natural sunlight. The production required careful choreography to fit the entire match within the extremely limited film capacity of early cameras. The fighters had to perform under hot studio lights and within the confined space of the boxing ring, all while maintaining authenticity for the camera. This was one of many boxing films Edison produced, capitalizing on the sport's popularity and its suitability for demonstrating motion picture technology.

Historical Background

This film was created during the pivotal year of 1895, which marked the true birth of cinema as a commercial medium. The Lumière brothers were preparing their first public screening in Paris, while in America, Thomas Edison and William K.L. Dickson were refining their Kinetoscope system. This period saw the transition from experimental motion studies to commercially viable entertainment. Boxing was experiencing a surge in popularity in late 19th-century America, with the sport gradually moving from illegal bare-knuckle contests to more respectable gloved matches. The film also reflects the Victorian fascination with physical culture and scientific documentation of human movement. The production occurred during the Gilded Age, a time of rapid industrialization and technological innovation in America, with Edison's laboratory in West Orange being at the forefront of this revolution. The film's creation predates the era of projected cinema for mass audiences, instead serving the niche market of Kinetoscope parlor patrons who were experiencing moving images for the first time.

Why This Film Matters

As one of the earliest boxing films ever produced, 'Billy Edwards and the Unknown' holds immense cultural significance as a pioneering work in both sports documentation and cinema history. It represents the birth of sports broadcasting, establishing boxing as one of the first sports to be captured on film and setting a precedent that would continue for over a century. The film demonstrates how early cinema immediately recognized the commercial potential of sports entertainment, a relationship that would become fundamental to both industries. It also serves as an important historical document of late 19th-century boxing culture, preserving the techniques and atmosphere of the sport's transitional period from bare-knuckle to gloved competition. The film contributed to the popularization of both cinema and boxing, with each medium helping to promote the other. Its existence shows that from cinema's earliest days, there was an understanding that audiences wanted to see real people doing real things, establishing the documentary impulse that would become central to film culture. The film also represents an early example of how new technologies capture and preserve cultural practices for future generations.

Making Of

The production of 'Billy Edwards and the Unknown' took place in Edison's revolutionary Black Maria studio, a tar-paper-covered building that could rotate on tracks to follow the sun's movement across the sky. William K.L. Dickson, Edison's chief engineer and the inventor of the Kinetograph camera, personally supervised and likely operated the camera for this filming. The studio's cramped conditions meant that the boxing ring had to be smaller than regulation size, and the fighters had to adjust their movements accordingly. The film was created as part of Edison's strategy to produce content for his Kinetoscope parlors, where customers paid 25 cents to view short films through individual viewing machines. The production team faced numerous technical challenges, including the need for extremely bright lighting (often achieved with multiple arc lamps that generated intense heat) and the limitation of early film stock, which could only capture about 20-30 seconds of footage per load. The presence of spectators in the background was carefully staged to create the illusion of a genuine sporting event, though these were likely studio employees or local residents recruited for the shoot.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Billy Edwards and the Unknown' represents the state of the art in 1895 motion picture photography. The film was shot using Dickson's Kinetograph camera, which was stationary and captured the action from a single, fixed perspective. The camera was hand-cranked, resulting in slight variations in frame rate throughout the filming. The composition places the boxing ring centrally in the frame, with the spectators visible in the background to provide context and scale. The lighting was provided by intense arc lamps that created harsh shadows and high contrast, typical of early studio photography. The entire film was shot in long take without any camera movement or editing, as these techniques had not yet been developed. The black and white imagery shows the characteristic grain of early film stock, and the motion blur during fast movements reflects the limitations of the camera's shutter speed. Despite these technical constraints, the cinematography successfully captures the essential action of the boxing match, demonstrating the medium's ability to document real events.

Innovations

This film represents several important technical achievements in early cinema history. It demonstrates the successful capture of rapid human movement using early motion picture technology, which was a significant challenge given the limitations of 1895 equipment. The production showcases Edison's 35mm film format, which would become the industry standard for over a century. The film also exemplifies early studio lighting techniques, using artificial illumination to create sufficient exposure for the relatively insensitive film stock of the era. The ability to film continuous action for approximately one minute was itself a technical milestone, pushing the boundaries of early camera design. The production also represents an early understanding of how to stage action for the camera, with the boxing match providing clear, easily readable movement that worked well within the technical constraints. The film's existence demonstrates the successful development of a complete production pipeline, from filming to exhibition, establishing the basic model that would evolve into the film industry.

Music

The film was originally produced as a silent work, as synchronized sound technology would not be developed for another three decades. When exhibited in Kinetoscope parlors, viewers would watch through individual viewing machines without any audio accompaniment. In modern screenings or presentations of the film, it is sometimes shown with period-appropriate music, typically piano compositions from the 1890s or selections from popular songs of the era. Some contemporary presentations might include sound effects to enhance the viewing experience, though these are not part of the original work. The silence of the original film actually contributes to its historical authenticity, reflecting the technological limitations of early cinema and allowing viewers to focus on the visual aspects of the boxing demonstration.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing Billy Edwards and Warwick entering the boxing ring and preparing for their exhibition match, capturing the formal beginning of the bout and establishing the presence of the crowd gathered to watch the demonstration of early cinema's ability to capture sporting action.

Did You Know?

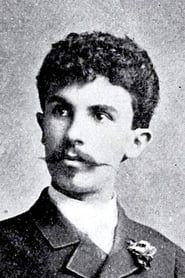

- Billy Edwards (1840-1907) was a real boxing champion who fought in the era of bare-knuckle boxing and later became one of the sport's first historians and journalists

- The film was created for exhibition in Edison's Kinetoscope peep-show devices, where viewers would watch individually through a viewer

- Boxing was one of the most popular subjects for early films because it showcased movement and action, demonstrating the capabilities of the new medium

- The Black Maria studio where this was filmed was the world's first movie production studio, built specifically for Edison's film experiments

- Early boxing films like this one were often staged exhibitions rather than actual competitive matches, allowing for better control of filming conditions

- The film was shot on 35mm film at approximately 16 frames per second, the standard rate for early motion pictures

- William K.L. Dickson, Edison's primary assistant in film development, personally operated the camera for many of these early productions

- The identity of 'Warwick' remains unknown to film historians, as was common with many early film subjects who were everyday people rather than professional actors

- This film represents one of the earliest examples of sports documentation in cinema history

- The short duration of each round (20 seconds) was likely dictated by the maximum length of film that could be loaded into early cameras

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of 'Billy Edwards and the Unknown' is difficult to document as film criticism as we know it did not exist in 1895. Reviews of Edison's Kinetoscope films appeared primarily in newspapers and technical journals, focusing more on the novelty of the technology than on artistic merit. The film was generally described in terms of its technical achievement and the lifelike quality of the motion it captured. Modern film historians and critics recognize the work as an important example of early cinema's documentary impulse and its role in establishing sports as a popular film subject. The film is now studied as a crucial artifact from the dawn of cinema, valued for its historical significance rather than its entertainment value. Contemporary scholars appreciate it as evidence of early filmmakers' understanding of what would appeal to audiences and their technical ingenuity in capturing action within severe limitations.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception in 1895 was overwhelmingly positive, as any moving image was a source of wonder and amazement to viewers experiencing the technology for the first time. Kinetoscope parlor patrons were particularly drawn to boxing films because they featured dynamic action and clear movement, making the illusion of life particularly convincing. The film would have been experienced individually through the Kinetoscope viewer, with each viewer having a private, intimate encounter with the moving images. Reports from the period suggest that viewers were often astonished by the realism of the motion and would sometimes attempt to interact with the images or watch the same film multiple times. The popularity of boxing films like this one helped establish the commercial viability of motion pictures and demonstrated that audiences would pay to see recorded events. Modern audiences encountering the film through archives or museums typically view it with historical curiosity, appreciating it as a window into both the early days of cinema and late 19th-century sporting culture.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Eadweard Muybridge's motion studies

- Étienne-Jules Marey's chronophotography

- Thomas Edison's earlier film experiments

- Popular boxing exhibitions of the 1890s

This Film Influenced

- The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight (1897)

- The Gordon Sisters Boxing (1901)

- Other early Edison boxing films

- Subsequent sports documentary films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Library of Congress collection as part of the paper print collection, where early films were submitted for copyright protection by printing them on paper rolls. It has been digitally restored and is available for viewing through various film archives and educational institutions. The survival of this film is remarkable given the fragile nature of early nitrate film stock, and its preservation allows modern audiences to witness one of cinema's earliest attempts at sports documentation.