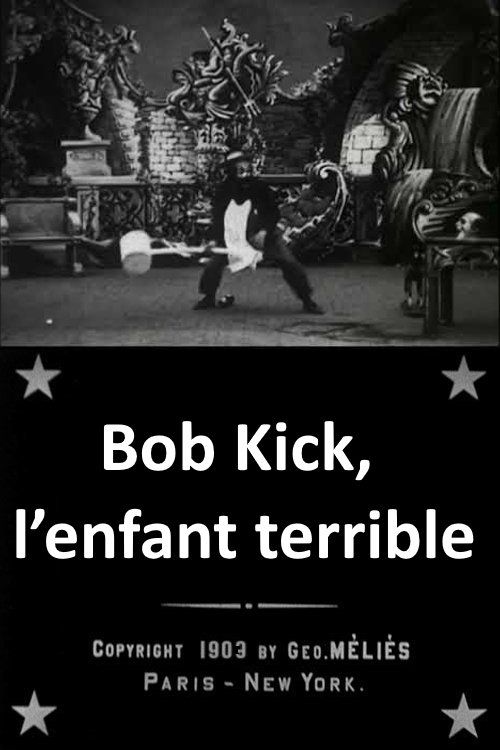

Bob Kick, the Mischievous Kid

Plot

The film opens with two nursemaids leading a young boy named Bob Kick into a theatrical setting where they present him with a large ball to play with. What follows is a rapid succession of magical transformations and visual tricks characteristic of Méliès's style - heads appear and disappear mysteriously, stage props explode and metamorphose into different objects or people, and reality itself seems to bend to the whims of the mischievous child. The sequence of transformations grows increasingly elaborate and surreal, with characters materializing from thin air and objects changing form in impossible ways. The film culminates in Bob Kick himself vanishing from the frame, leaving behind an empty stage as if all the magic was merely a product of his childish imagination. The entire piece serves as a showcase of early cinematic special effects and the limitless possibilities of the new medium of film.

Director

Cast

About the Production

Filmed in Méliès's glass-walled studio which allowed for natural lighting and contained elaborate stage machinery for his theatrical effects. The film utilized multiple exposure techniques, substitution splices, and dissolves that Méliès pioneered. The production would have involved careful choreography of the actors and precise timing for the special effects sequences.

Historical Background

1903 was a pivotal year in early cinema, occurring just eight years after the Lumière brothers' first public film screening. The film industry was still in its infancy, with most films being short actualities or simple trick films. Méliès was one of the few filmmakers creating narrative content with elaborate special effects. This period saw the beginning of the shift from novelty films to more sophisticated storytelling. The film was made during the Belle Époque in France, a time of artistic innovation and cultural flourishing. Cinema was transitioning from fairground attraction to legitimate art form, and Méliès was at the forefront of this evolution. The early 1900s also saw the establishment of permanent movie theaters and the development of film distribution networks, allowing works like this to reach international audiences.

Why This Film Matters

Bob Kick, the Mischievous Kid represents an important milestone in the development of cinematic language and visual effects. The film exemplifies Méliès's role in establishing cinema as a medium for fantasy and imagination rather than just reality. Its influence can be seen in countless later films featuring magical transformations and impossible physics. The work demonstrates how early filmmakers adapted theatrical magic techniques for the camera, creating a new visual vocabulary that would evolve into modern special effects. The film also reflects the Victorian fascination with childhood innocence and mischief, themes that would recur throughout cinema history. Méliès's approach to visual storytelling helped establish the fantasy genre and influenced generations of filmmakers, from Walt Disney to contemporary directors of magical realism.

Making Of

Georges Méliès, a former magician and theater owner, brought his theatrical expertise to this short film, transforming his glass studio into a magical playground. The production relied heavily on his innovative use of in-camera effects rather than post-production editing. Méliès would meticulously plan each transformation, often requiring actors to freeze in position while he stopped the camera to make changes. The hand-coloring process was labor-intensive, with teams of women carefully applying paint to each individual frame. Méliès's background in stage magic meant he understood precisely how to create illusions that would translate effectively to the new medium of cinema. The film's theatrical sets were built with trap doors and hidden compartments to facilitate the various magical appearances and disappearances that characterize the piece.

Visual Style

The cinematography reflects Méliès's theatrical background, featuring a static camera positioned as if viewing a stage performance. This approach allowed the audience to focus on the magical transformations occurring within the frame. The lighting was natural, coming through the glass walls of Méliès's studio, creating a bright, clear image essential for the special effects to be visible. The camera work was precise and deliberate, with each shot carefully composed to maximize the impact of the visual tricks. The film employed multiple exposure techniques and substitution splices that required exact framing and timing to execute successfully.

Innovations

The film showcases several of Méliès's pioneering technical innovations, including substitution splices (stopping the camera to change elements in the frame), multiple exposures, and dissolves. These techniques, while common today, were revolutionary in 1903 and required precise timing and planning. Méliès developed many of these effects by accident when his camera jammed, leading to unexpected jump cuts that appeared magical. The film also demonstrates early use of props designed specifically for cinematic effect rather than theatrical use. The hand-coloring process, while not invented by Méliès, was perfected in his studio and represents an early form of color in cinema.

Music

As a silent film from 1903, Bob Kick, the Mischievous Kid had no original soundtrack. In theaters, it would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small orchestra playing popular tunes of the era or improvising to match the on-screen action. The musical accompaniment would have been crucial in creating atmosphere and guiding audience emotional responses to the magical events. Modern screenings often feature contemporary scores composed specifically for Méliès's films, typically using period-appropriate instrumentation to maintain historical authenticity.

Famous Quotes

(Silent film - no dialogue, but intertitles may have included: 'Bob Kick, the mischievous child, enters with his nursemaids')

Memorable Scenes

- The sequence where heads appear and disappear from thin air, showcasing Méliès's mastery of substitution splices

- The moment when the large ball transforms into another object or person, demonstrating the film's theme of magical transformation

- The final disappearance of Bob Kick himself, bringing the magical journey full circle

Did You Know?

- The film is cataloged as Star Film #449 in Méliès's production list

- Méliès himself played the role of Bob Kick, continuing his practice of starring in many of his own films

- The title character's name 'Bob Kick' was likely chosen to sound exotic and foreign to French audiences

- The film showcases Méliès's mastery of substitution splices, where he would stop the camera, change elements in the scene, then resume filming

- Like many Méliès films, it was hand-colored in some releases, with each frame individually painted

- The film was distributed internationally, including in the United States through Méliès's American distribution deal

- The nursemaids in the film were likely played by Jehanne d'Alcy, Méliès's frequent collaborator and later second wife

- The ball given to Bob Kick was probably oversized for comedic effect and to make it more visible in the frame

- This film represents Méliès's continued exploration of childhood themes and magical realism

- The disappearing act at the end was achieved through a jump cut, one of Méliès's signature techniques

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews from 1903 are scarce, as film criticism was not yet established as a formal practice. However, Méliès's films were generally popular with audiences and exhibitors for their entertaining and innovative qualities. Modern critics and film historians recognize Bob Kick as a representative example of Méliès's style and technical prowess. The film is appreciated today for its historical importance and its role in the development of cinematic special effects. Film scholars often cite it as an example of how early cinema drew from theatrical traditions while simultaneously establishing new forms of visual expression unique to the medium.

What Audiences Thought

Early 20th century audiences reportedly found Méliès's magical films delightful and astonishing, as they had never seen such visual trickery before. The film's brief runtime and continuous stream of visual surprises made it ideal for the variety show format common in early cinema exhibition. Modern audiences viewing the film in retrospectives or on streaming platforms often express fascination with the ingenuity of the effects given the technological limitations of the era. The film serves as a window into the wonder that early cinema audiences must have experienced when seeing these impossible transformations for the first time.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage magic traditions

- Victorian theater

- Fairy tales

- Commedia dell'arte

- Parisian café-concert performances

This Film Influenced

- The Dream of a Rarebit Fiend (1906)

- The Great Train Robbery (1903)

- Alice in Wonderland adaptations

- Fantasia (1940)

- Harry Potter film series

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in various archives and collections, including the Cinémathèque Française. Some versions exist in black and white, while others retain their original hand-coloring. The film has been restored and digitized by several film preservation organizations and is available through various classic film collections.