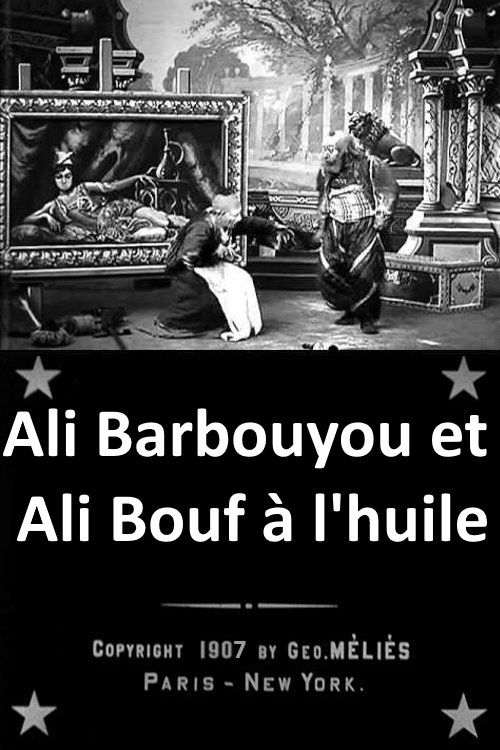

Delirium in a Studio

Plot

A painter has just completed his masterpiece when his assistant enters the studio. In a moment of carelessness, the assistant accidentally drinks varnish, which causes him to become delirious. The painter, observing the assistant's altered state, becomes increasingly agitated and begins to experience his own form of madness. In a fantastical sequence, the painter uses his supernatural powers to literally push his assistant into the completed painting, where the assistant becomes trapped within the artwork. The film culminates with the painter's complete breakdown as he destroys his own studio in a fit of artistic rage, demonstrating the thin line between creative genius and madness.

Director

Cast

About the Production

This film was shot entirely in Méliès's studio in Montreuil-sous-Bois, which was essentially a glass-walled building that allowed for natural lighting. The film utilized Méliès's signature substitution splices and multiple exposure techniques to create the magical effects of the assistant being pushed into the painting. The painted backdrop was created by Méliès himself, who was originally a professional magician and theater set designer before entering cinema.

Historical Background

1907 was a pivotal year in early cinema, occurring just twelve years after the Lumière brothers' first public screening. During this period, cinema was transitioning from simple actualities and trick films to more complex narratives. Méliès was one of the few filmmakers who had developed a distinctive cinematic language, using editing tricks and special effects to create fantastical stories that couldn't exist in theater. This film emerged during the height of Méliès's influence, before his career was severely damaged by the monopolistic practices of Thomas Edison's Motion Picture Patents Company and Pathé Frères, which would eventually drive him to bankruptcy.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents Méliès's exploration of the relationship between art and madness, a theme that would recur throughout cinema history. It demonstrates early cinema's fascination with the supernatural and the breakdown of reality, themes that would become staples of horror and fantasy genres. The film also showcases Méliès's pioneering use of cinematic space, treating the frame as a canvas where reality could be manipulated. This approach influenced countless future filmmakers, from German Expressionists to surrealist directors. The film's preservation and continued study highlight its importance in understanding the evolution of visual storytelling and special effects in cinema.

Making Of

The film was created during what many consider the peak of Méliès's creative period (1906-1909). Méliès built his own studio in 1897, which was essentially a theater with glass walls and a painted backdrop that could be changed. This allowed him to perfect his cinematic magic tricks. The actor Manuel, who played the assistant, was one of Méliès's regular collaborators. The film's special effects required precise timing and multiple exposures, with Méliès having to manually crank the camera while orchestrating the actors' movements. The painting that serves as the portal was actually a large backdrop that Méliès painted himself, combining his skills as a visual artist with his cinematic innovations.

Visual Style

The cinematography, typical of Méliès's work, uses a static camera positioned to capture the entire stage-like set. This theatrical approach allowed Méliès to choreograph complex actions and transformations within a single frame. The film employs substitution splicing to create magical effects, where the camera would be stopped, objects or actors would be changed, and filming would resume. Multiple exposures were likely used to create the effect of the assistant merging with the painting. The lighting was natural, coming through the glass walls of Méliès's studio, creating a consistent illumination that was essential for the special effects.

Innovations

The film showcases several of Méliès's signature technical innovations, including substitution splicing, multiple exposure, and careful matte work. The effect of pushing the assistant into the painting required precise timing and likely involved a combination of techniques: first, a substitution splice to make the assistant disappear, followed by a double exposure to show his form merging with the painted backdrop. The film also demonstrates Méliès's mastery of spatial manipulation within the cinematic frame, creating the illusion of depth and interaction between live actors and painted scenery. These techniques, while common in Méliès's work, were groundbreaking for their time and influenced the development of special effects cinema.

Music

As a silent film from 1907, 'Delirium in a Studio' was originally presented without a synchronized soundtrack. During its initial theatrical run, it would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small orchestra who would improvise or use pre-selected pieces to match the action on screen. The musical accompaniment would have emphasized the film's increasingly frantic pace and dramatic moments. Modern screenings of the film often feature newly composed scores or period-appropriate classical music to recreate the original viewing experience.

Famous Quotes

(Intertitle) A painter has just finished his work when his assistant comes in and accidentally drinks varnish

(Intertitle) The painter goes haywire and sends the assistant into the painting

Memorable Scenes

- The climatic sequence where the painter, in a fit of madness, literally pushes his assistant through the canvas and into the painted world, achieved through Méliès's masterful substitution splicing and creating one of cinema's earliest examples of breaking the barrier between reality and art

Did You Know?

- This film is also known by its French title 'Délire dans un atelier' and was cataloged by Méliès's Star Film Company as No. 988-989

- Georges Méliès not only directed but also starred in the film, playing the role of the painter

- The film showcases Méliès's fascination with the theme of artists and madness, which appeared in several of his other works

- The special effect of pushing the assistant into the painting was achieved through a combination of substitution splicing and careful staging

- This was one of over 500 films Méliès created during his prolific career

- The film was hand-colored in some releases, a common practice for Méliès's more important productions

- The varnish-drinking sequence was likely simulated using a colored liquid, as actual varnish would have been too dangerous for the actor

- Méliès's glass studio allowed him to control lighting precisely, which was crucial for his complex special effects

- The destruction of the studio at the film's end was one of Méliès's more elaborate set destruction sequences

- This film was distributed internationally, including in the United States through the Star Film Company's American branch

What Critics Said

Contemporary reception of Méliès's films in 1907 was generally positive, with audiences marveling at his magical effects. Trade publications of the era praised his technical innovations and imaginative storytelling. Modern critics and film historians recognize 'Delirium in a Studio' as a representative example of Méliès's mature style, noting its sophisticated use of substitution splices and its thematic exploration of artistic madness. The film is often cited in scholarly works about early cinema as an example of how Méliès transformed cinematic tricks into narrative devices, moving beyond mere spectacle to tell stories with psychological depth.

What Audiences Thought

Early 20th-century audiences were captivated by Méliès's magical films, which were often shown as part of variety programs in music halls and fairgrounds. The impossible transformations and supernatural events in films like 'Delirium in a Studio' were seen as genuine wonders of the new medium. The film's theme of an artist's madness would have resonated with contemporary audiences who were fascinated by the romantic notion of the tortured genius. Today, the film is primarily viewed by film enthusiasts, students, and scholars who appreciate its historical significance and technical innovations.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage magic and theatrical illusions

- Victorian literature about mad artists

- Commedia dell'arte character archetypes

- Grand Guignol theater traditions

This Film Influenced

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

- Un Chien Andalou (1929)

- The Mystery of the Blue Room (1932)

- Vertigo (1958)

- The Shining (1980)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in archives and has been preserved by various film institutions, including the Cinémathèque Française. Some versions exist in their original black and white, while others show evidence of hand-coloring. The film has been digitally restored as part of various Méliès retrospectives and is included in several DVD and Blu-ray collections of his complete works.