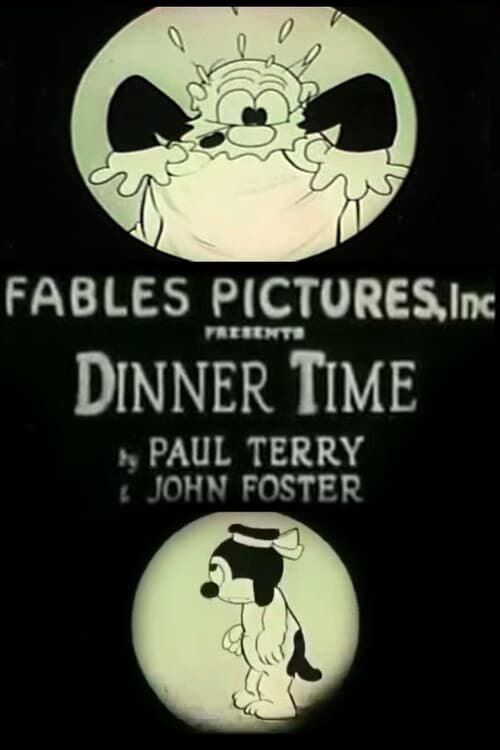

Dinner Time

"The First Sound Cartoon of the New Era!"

Plot

Dinner Time follows the comedic misadventures of a family of anthropomorphic animals preparing for their evening meal. The father character struggles to bring home dinner while facing various obstacles and predators. The cartoon features synchronized sound effects and dialogue, with characters reacting to the auditory elements of their environment. The plot centers around the universal theme of hunger and the challenges of obtaining food in a humorous, animated setting. The short concludes with the family finally enjoying their meal together after numerous slapstick complications.

Director

About the Production

Produced in response to the success of 'The Jazz Singer' (1927), this cartoon was created using the Phonofilm sound-on-film system developed by Lee De Forest. The production team worked quickly to capitalize on the new sound technology, recording synchronized dialogue and sound effects directly onto the film strip. The animation was done using traditional cel animation techniques but required careful timing to match the new audio elements.

Historical Background

Dinner Time was created during a revolutionary period in cinema history following the success of Warner Bros.' 'The Jazz Singer' in 1927, which proved that talking pictures were commercially viable. The film industry was in rapid transition from silent to sound technology, with studios scrambling to adapt their production methods. Animation studios faced unique challenges in this transition, as their established visual comedy styles had to be reimagined for sound. The late 1920s saw intense competition between animation pioneers, with Paul Terry, Walt Disney, and others racing to create successful sound cartoons. This period also coincided with the growth of movie theaters and the increasing popularity of short subjects as part of theatrical programs.

Why This Film Matters

Dinner Time represents a crucial milestone in animation history as one of the very first cartoons to feature synchronized sound. While Steamboat Willie often receives more historical attention, Dinner Time demonstrates that the transition to sound animation was happening across multiple studios simultaneously. The film helped establish the template for sound cartoons, showing how dialogue, music, and sound effects could enhance animated storytelling. It contributed to the rapid evolution of animation from a visual-only medium to a multi-sensory art form. The cartoon's commercial success, despite technical limitations, proved that audiences were ready for sound animation, encouraging further investment and innovation in the field. This early experiment paved the way for the golden age of animation that would follow in the 1930s.

Making Of

The production of Dinner Time marked a pivotal moment in animation history as studios rushed to adapt to sound technology. Paul Terry's team worked intensively to incorporate synchronized audio, a revolutionary concept at the time. The animators had to modify their traditional techniques to account for timing with sound, requiring careful coordination between the visual and audio departments. The voice actors and sound effects artists performed in real-time while watching the animated footage, creating a primitive form of dubbing. The rushed production schedule meant that the quality of synchronization wasn't always perfect, but it demonstrated the potential of sound in animation. The success of this experiment convinced Terry to invest more heavily in sound technology for future productions.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Dinner Time utilized traditional cel animation techniques of the late 1920s, with black and white imagery and limited movement by modern standards. The visual style was typical of Terrytoons productions, with simple character designs and backgrounds. The animation team had to carefully time their drawings to match the newly added sound elements, requiring more precise planning than silent cartoons. The camera work was straightforward, focusing on clear storytelling without complex angles or movements. The visual comedy relied on exaggerated actions and expressions that would later become staples of animation but were still evolving during this period.

Innovations

Dinner Time's primary technical achievement was its successful implementation of synchronized sound in animation, making it one of the first cartoons to accomplish this feat. The film utilized Lee De Forest's Phonofilm system, which recorded audio directly onto the film strip, eliminating the need for separate discs. The production team developed new techniques for timing animation to match sound, creating a more complex workflow than silent cartoons. The cartoon demonstrated that dialogue could be effectively integrated into animated storytelling, not just music and sound effects. While the technology was primitive compared to later systems, it proved that sound animation was commercially viable and artistically promising. The film's technical innovations, despite their limitations, helped establish the foundation for modern animated films.

Music

The soundtrack of Dinner Time was groundbreaking for its time, featuring synchronized dialogue, sound effects, and musical accompaniment recorded using Lee De Forest's Phonofilm system. The audio was recorded directly onto the film strip, creating a primitive but effective sound-on-film format. The musical score was typical of late 1920s cartoon accompaniment, with jaunty tunes that matched the on-screen action. Sound effects were created live during recording, using various props and vocal techniques. The dialogue, while rudimentary by modern standards, demonstrated that animated characters could speak and be understood by audiences. The overall sound quality was limited by the technology of the era, with noticeable hiss and occasional synchronization issues.

Famous Quotes

It's dinner time! Dinner time!

I'm hungry as a bear!

No dinner for you tonight!

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where the father character announces 'It's dinner time!' with synchronized voice, marking one of the first instances of spoken dialogue in animation history.

Did You Know?

- Dinner Time was actually completed BEFORE Disney's Steamboat Willie but released AFTER it, making it historically significant in the sound animation race

- It was part of the Aesop's Fables cartoon series produced by Paul Terry

- The cartoon used Lee De Forest's Phonofilm system for sound synchronization

- Paul Terry initially resisted adding sound to his cartoons but was convinced by the commercial success of The Jazz Singer

- The film's sound system was considered inferior to Disney's later use of the Cinephone system

- Only a handful of theaters were equipped to show sound films in 1928, limiting its initial distribution

- The cartoon featured synchronized dialogue, not just music and sound effects like some early sound cartoons

- Educational Pictures distributed the cartoon as part of their comedy short program

- The success of this cartoon helped establish Terrytoons as a major animation studio

- Despite its historical importance, the film is rarely shown today compared to Disney's early sound cartoons

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Dinner Time for its technical innovation in bringing sound to animation, though many noted that the synchronization wasn't as polished as Disney's efforts. The trade papers of the era recognized its historical importance as one of the first sound cartoons. Modern animation historians acknowledge the film's significance in the sound revolution while generally considering it technically inferior to Steamboat Willie. Critics have noted that the cartoon's humor relied heavily on the novelty of sound rather than sophisticated storytelling or animation techniques. Despite mixed reviews on its artistic merits, the film is universally recognized as an important stepping stone in animation history.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1928 were fascinated by the novelty of hearing animated characters speak and make synchronized sounds. The cartoon drew crowds to theaters equipped for sound projection, though its limited distribution meant many viewers never had the chance to see it. Those who did experience it were impressed by the technological achievement even if the content itself was relatively simple. The film's reception demonstrated that there was strong public appetite for sound animation, encouraging other studios to follow suit. Modern audiences viewing the cartoon today often appreciate its historical context more than its entertainment value, as animation techniques have evolved dramatically since 1928.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Jazz Singer (1927)

- Felix the Cat cartoons

- Aesop's Fables

- Mickey Mouse cartoons

- Vaudeville comedy routines

This Film Influenced

- Steamboat Willie (1928)

- Early Terrytoons sound cartoons

- Van Beuren sound cartoons

- Fleischer Studios sound cartoons

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film exists in archives and has been preserved by animation historians, though it's not widely available to the public. Some versions may have deteriorated due to the age of the nitrate film stock used in 1928. The Library of Congress and animation archives maintain copies for historical preservation.