Dr. Macintyre's X-Ray Film

Plot

Dr. Macintyre's X-Ray Film (1896) is a groundbreaking scientific documentary that captures moving X-ray images of biological processes. The film showcases three remarkable sequences: X-ray footage of a frog's knee joint in motion, revealing the mechanical movements of amphibian locomotion; a beating human heart, displaying the rhythmic contractions and expansions of cardiac muscle in real-time; and the movements of the human stomach during digestion. This pioneering work represents one of the earliest attempts to use moving pictures for scientific visualization and medical education, demonstrating the potential of cinematography as a tool for observing phenomena invisible to the naked eye.

Director

John MacintyreAbout the Production

Filmed using early X-ray equipment combined with cinematographic technology. The production required extremely sensitive photographic plates and long exposure times due to the primitive nature of early X-ray tubes. Dr. Macintyre had to overcome significant technical challenges including radiation safety concerns (before radiation dangers were fully understood), synchronization of X-ray pulses with film frame rates, and the development of suitable contrast agents to make internal structures visible.

Historical Background

The film was created during an extraordinary period of scientific discovery in the mid-1890s. 1895-1896 saw the emergence of both X-rays and motion pictures as transformative technologies. The Victorian era was characterized by rapid industrial and scientific progress, with the Royal Society of London serving as a prestigious forum for presenting new discoveries. Wilhelm Röntgen's discovery of X-rays in November 1895 had caused a worldwide sensation, with scientists and medical professionals racing to explore the applications of this mysterious new radiation. Simultaneously, the Lumière brothers' first public film screening in December 1895 marked the birth of cinema as a mass medium. Dr. Macintyre's film emerged at this unique intersection, representing one of the first attempts to use moving pictures for scientific documentation rather than entertainment. The film's presentation at the Royal Society placed it within the context of serious scientific inquiry rather than the popular entertainment venues where most early films were shown.

Why This Film Matters

Dr. Macintyre's X-Ray Film holds immense cultural and scientific significance as a pioneering work that bridged medicine, physics, and the emerging art of cinema. It demonstrated that moving pictures could serve as powerful tools for scientific visualization and education, a concept that would become fundamental to medical training and research. The film helped establish the field of radiology as a visual discipline, influencing how doctors and scientists would approach medical imaging for the next century. It also represented an early example of science communication, making invisible biological processes visible to both scientific and lay audiences. The film's existence showed that cinema could transcend entertainment and become a serious medium for documentation and education, influencing generations of documentary and scientific filmmakers. Its legacy can be seen in modern medical imaging technologies, MRI videos, and educational animations that continue to make the invisible visible.

Making Of

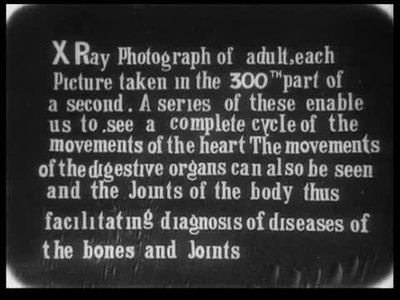

The production of Dr. Macintyre's X-Ray Film represented a remarkable convergence of two revolutionary technologies discovered within months of each other: X-rays (discovered by Wilhelm Röntgen in November 1895) and cinematography (developed by the Lumière brothers in 1895). Dr. John Macintyre, working at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary, quickly recognized the potential of combining these technologies. The filming process required custom-built equipment that could synchronize the X-ray tube's operation with the camera's shutter mechanism. The human heart sequence was particularly challenging to capture, as Macintyre had to develop methods to keep the subject still while allowing the heart to beat naturally. The stomach movements were filmed after the subject ingested a contrast medium (likely bismuth or barium sulfate) to make the digestive tract visible. The entire production was conducted in a makeshift laboratory, with Macintyre himself operating both the X-ray equipment and the camera, often working in darkness to properly expose the sensitive plates.

Visual Style

The cinematography was revolutionary for its time, utilizing early X-ray equipment combined with modified motion picture cameras. The visual style consisted of high-contrast, monochromatic images showing skeletal structures and organ movements as white shapes against dark backgrounds. The technique required extremely sensitive photographic plates and careful timing to capture moving subjects. The frog sequence demonstrated clear skeletal articulation, while the heart sequence showed the characteristic shape and movement patterns of cardiac muscle. The stomach footage revealed peristaltic waves moving through the digestive tract. The visual aesthetic was purely functional, prioritizing scientific clarity over artistic composition, though the resulting images possessed an eerie, ghostly quality that fascinated viewers.

Innovations

This film represents multiple groundbreaking technical achievements: it was the first successful synchronization of X-ray equipment with motion picture cameras; it demonstrated the feasibility of recording moving internal biological processes; it pioneered techniques for medical imaging that would evolve into modern fluoroscopy; it established methods for using contrast agents in moving X-ray images; it overcame the technical limitations of early X-ray tubes and photographic materials to produce clear moving images; it developed protocols for subject positioning and stabilization during medical imaging; and it created the foundation for the entire field of medical cinematography and radiological documentation.

Music

Silent film - no soundtrack was produced or used during the original presentations

Famous Quotes

'We have now the power to see within the living body as it functions' - Dr. John Macintyre, 1896

'The moving picture of the beating heart presents to us a spectacle never before witnessed by human eyes' - Royal Society proceedings, 1896

Memorable Scenes

- The sequence showing the beating human heart, with its rhythmic contractions clearly visible through the X-ray imaging, represents one of the most remarkable moments in early scientific filmmaking, revealing the living organ in motion for the first time in history.

Did You Know?

- This is considered the first X-ray cinematograph film ever created

- Dr. John Macintyre was a medical doctor who pioneered the use of X-rays in clinical practice

- The film was demonstrated at the Royal Society of London in both 1896 and again in 1909

- Wilhelm Röntgen had only discovered X-rays in November 1895, making this film created within months of the discovery

- The frog knee joint sequence was particularly significant as it demonstrated clear skeletal movement

- Early X-ray films like this were often called 'shadowgraphs' due to the shadow-like nature of the images

- The production required subjects to remain extremely still during filming due to long exposure times

- Dr. Macintyre later became one of the first radiologists to use X-rays for medical diagnosis

- The film predates the establishment of radiation safety protocols by decades

- This film helped establish the foundation for modern medical imaging and fluoroscopy

What Critics Said

Contemporary scientific reception was overwhelmingly positive, with members of the Royal Society expressing astonishment at the ability to see internal biological processes in motion. The medical community recognized the immediate diagnostic potential of such technology. The film was described in scientific journals as 'revolutionary' and 'opening new horizons in medical science.' Modern film historians and medical historians view the film as a crucial milestone in both cinema history and medical history, though it remains largely unknown to the general public due to its specialized nature and age. Critics today emphasize its importance as a foundational work in scientific visualization and medical imaging.

What Audiences Thought

The primary audience consisted of members of the Royal Society and medical professionals, who received the film with wonder and excitement. Reports from the 1896 and 1909 presentations describe audiences as 'spellbound' and 'astonished' by the moving X-ray images. Medical professionals immediately recognized the diagnostic potential, while scientists appreciated the technical achievement. The film was not shown to general audiences as it was considered a scientific demonstration rather than entertainment. Those who did see it reported that it changed their understanding of both the capabilities of X-rays and the potential of moving pictures as scientific tools.

Awards & Recognition

- None - predates formal film award ceremonies

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Wilhelm Röntgen's X-ray discovery

- Lumière brothers' cinematography

- Early medical photography

- Scientific illustration traditions

- Victorian scientific documentation

This Film Influenced

- Early medical documentaries

- Fluoroscopy training films

- Medical imaging educational videos

- Scientific visualization films

- Modern MRI and ultrasound video documentation

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The original film is believed to be lost or severely degraded due to the instability of early nitrate film stock and the chemical processes used in X-ray imaging. Some reports suggest that copies or fragments may exist in archival collections, possibly at the British Film Institute or Royal Society archives, but no complete verified version is known to survive. Historical descriptions and scientific papers provide detailed accounts of the film's content, but the actual moving images are considered lost to time.