Execution of Czolgosz with Panorama of Auburn Prison

"A Startling Realization of the Execution of the Assassin of Our Late Beloved President McKinley"

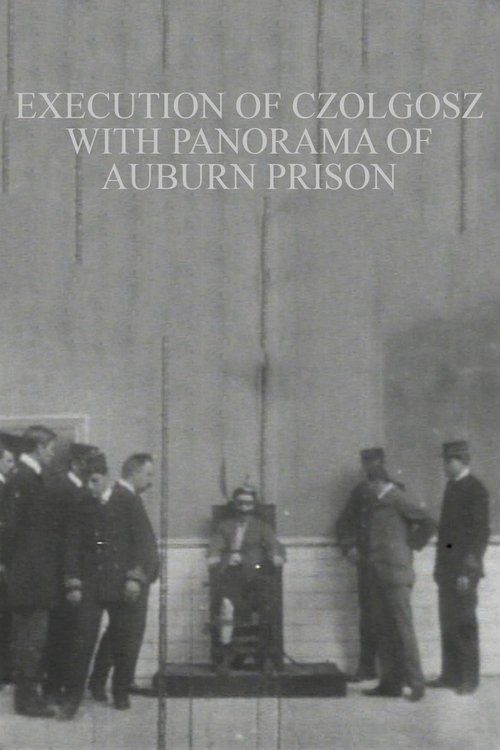

Plot

This pioneering docudrama opens with a panoramic view of Auburn Prison in New York, showing the imposing exterior walls and guard towers. The film then transitions to a reconstructed death chamber where actors recreate the execution of Leon Czolgosz, the anarchist who assassinated President William McKinley. The sequence shows guards escorting the condemned man to the electric chair, strapping him in, and the simulated electrocution itself. The film concludes with the removal of the body, providing viewers with a complete visual narrative of the execution process. This remarkable early film blends documentary footage of the actual prison with staged recreation of the execution, creating what is considered one of cinema's first docudramas.

Director

About the Production

The film was produced and released within weeks of Czolgosz's actual execution on October 29, 1901, demonstrating Edison's rapid response to current events. The production combined actual footage of Auburn Prison's exterior with a meticulously reconstructed death chamber built in Edison's studio. The electric chair used in the recreation was a detailed replica, and actors were hired to portray the prison guards and witnesses. This hybrid approach of documentary and staged elements was innovative for its time and established a template for future docudramas.

Historical Background

This film was produced in the immediate aftermath of one of the most traumatic events in early 20th-century American history - the assassination of President William McKinley. McKinley was shot on September 6, 1901, at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo by Leon Czolgosz, a self-proclaimed anarchist. The President died on September 14, 1901, and Czolgosz was quickly tried, convicted, and executed on October 29, 1901. The nation was gripped by fascination and horror surrounding these events, with newspapers providing extensive coverage. This film emerged in the context of early cinema's evolution from simple actualities to more complex narrative forms. It also reflected the era's fascination with crime, punishment, and the relatively new method of execution by electric chair, which had been introduced only a decade earlier.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents a pivotal moment in cinema history, marking the transition from simple documentary recordings to sophisticated recreations of current events. It established the docudrama as a viable commercial genre and demonstrated cinema's power to bring distant events to mass audiences. The film's commercial success proved that audiences were hungry for visual representations of news stories, paving the way for future newsreels and current events programming. It also raised early questions about the ethics of recreating tragic events for entertainment, a debate that continues in documentary filmmaking today. The film's existence highlights how quickly the new medium of cinema adapted to serve public curiosity about current events, essentially functioning as an early form of visual journalism.

Making Of

The production of this film exemplified Edison Manufacturing Company's aggressive approach to capitalizing on current events. Edwin S. Porter, who would become one of early cinema's most important directors, was tasked with creating a visual representation of the highly publicized execution. The production team traveled to Auburn Prison to capture authentic exterior footage, then returned to Edison's Bronx studio to construct a detailed replica of the death chamber. The electric chair was meticulously recreated based on available descriptions and newspaper illustrations. Actors were cast to play the prison officials and witnesses, with careful attention to authentic uniforms and period details. The filming technique involved stationary camera positions typical of the era, with the action arranged to occur within the single frame. The simulated electrocution effects were achieved through dramatic lighting changes and the actor's performance, creating a convincing illusion for audiences of the time.

Visual Style

The cinematography reflects the technical limitations and conventions of 1901 filmmaking. The camera remains stationary throughout, positioned to capture the entire scene in a single wide shot, typical of early cinema's theatrical influence. The exterior prison footage was shot in bright daylight, creating stark contrasts with the interior execution chamber scenes, which were lit dramatically to enhance the somber mood. The composition carefully arranges the action within the frame, with the electric chair positioned as the central focal point. The film demonstrates Edwin S. Porter's emerging skill in staging action for the camera, with careful attention to spatial relationships and blocking. The visual style emphasizes clarity and readability over artistic expression, as was common in early narrative films.

Innovations

This film represents several important technical innovations for its time. It pioneered the hybrid approach of combining actual documentary footage with staged recreation, a technique that would become fundamental to documentary and docudrama filmmaking. The production demonstrated advanced set design and construction capabilities for the period, creating a convincing replica of the prison death chamber. The film also showcased early special effects techniques in simulating the electrocution through lighting manipulation and performance. The seamless integration of location footage with studio work was technically sophisticated for 1901. Additionally, the film's rapid production timeline - from actual event to screen in just a few weeks - demonstrated the emerging efficiency of commercial film production.

Music

As a silent film from 1901, there was no synchronized soundtrack. The film would have been accompanied by live musical performance typical of the era, usually a pianist or small ensemble in the theater. The music would have been selected to match the solemn and dramatic nature of the subject matter, likely including classical pieces or popular songs of the period that evoked appropriate emotions. Some theaters might have used sound effects created manually, such as thunder sheets or other devices to simulate the electrical execution. The musical accompaniment would have varied significantly from venue to venue, as there was no standardized scoring for films of this period.

Famous Quotes

No dialogue exists for this silent film - the title itself served as the primary descriptive text: 'Execution of Czolgosz with Panorama of Auburn Prison'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening panoramic sweep of Auburn Prison's imposing exterior walls and guard towers, establishing the institutional setting. The dramatic recreation of Czolgosz being led to the electric chair by prison guards in period-accurate uniforms. The simulated electrocution sequence, achieved through dramatic lighting changes and the actor's convulsions, which was so convincing many viewers believed it authentic. The final scene showing the removal of the 'body' from the chair, completing the narrative arc of justice served.

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first films to recreate a contemporary news event, establishing the docudrama genre

- The film was released just weeks after Czolgosz's actual execution, capitalizing on public fascination with the event

- Edison's company marketed it as 'educational' despite its sensational nature

- The film was so realistic that some viewers believed they were watching actual footage of the execution

- This was one of Edwin S. Porter's earliest directorial efforts before his landmark film 'The Great Train Robbery' (1903)

- The actual execution was not filmed, as cameras were forbidden in the death chamber

- The film's title was deliberately lengthy and descriptive, common for early cinema to attract audiences

- Auburn Prison was the site of the first execution by electric chair in history in 1890

- The film was part of Edison's strategy to produce 'actuality' films that brought current events to mass audiences

- Some theaters refused to show the film due to its graphic subject matter

What Critics Said

Contemporary reception of the film was mixed but largely positive in terms of commercial success. Trade publications like The New York Clipper and The Moving Picture World noted the film's technical achievement in recreating such a sensitive subject matter. Some critics praised Edison's innovation in combining actual footage with staged recreation, while others questioned the propriety of depicting an execution for entertainment. The film was widely discussed in newspapers, with many reviewers noting its startling realism. Modern film historians recognize it as an important milestone in the development of narrative cinema and the docudrama genre, though they also acknowledge its role in the early sensationalism that would characterize much of news entertainment.

What Audiences Thought

The film generated tremendous public interest and was a commercial success for Edison Manufacturing Company. Audiences were drawn by the morbid curiosity of seeing a recreation of the execution that had dominated newspaper headlines for weeks. Many viewers reportedly believed they were watching authentic footage of the actual execution, despite the impossibility of such filming. The film played to packed houses in vaudeville theaters and other venues that showed Edison pictures. Some audience members found the subject matter disturbing, and a few theaters reportedly refused to exhibit it on moral grounds. Nevertheless, the film's popularity demonstrated the public's appetite for visual representations of current events and helped establish cinema as a legitimate source for news and information.

Awards & Recognition

- None - film awards did not exist in 1901

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Actualities and documentary films of the Lumière brothers

- Edison's earlier 'Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots' (1895)

- Contemporary newspaper journalism and illustrated news coverage

- Stage melodramas and theatrical executions

This Film Influenced

- The Great Train Robbery (1903) - also directed by Porter

- The Life of an American Fireman (1903) - another Porter docudrama

- The Electrocuting of an Elephant (1903) - another Edison execution film

- Future newsreels and current events programming

- The entire docudrama genre in cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art's film collection. It has been digitally restored and is available through various archival sources. The preservation quality is considered good for a film of this vintage, though some deterioration is evident. The film is part of the National Film Registry's collection of historically significant American films.