Grandmother's Tale and Child's Dream

Plot

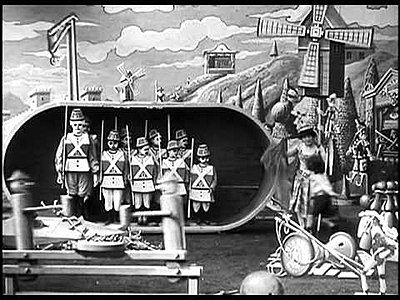

The film opens with a tender domestic scene where a grandmother lovingly reads a bedtime story to her young grandchild before tucking them into bed for the night. As soon as the child drifts off to sleep, their dreamscape comes alive with the appearance of a benevolent angel who descends from above and gently lifts the sleeping child, transporting them to a magical realm inhabited by giant, oversized toys that tower over the dreaming child. The young protagonist wanders through this fantastical toyland in wonderment before encountering a mysterious lady who guides them deeper into the dream world, eventually leading them to an enchanted forest where ethereal young women dressed as delicate butterflies perform an enchanting dance amidst the trees. The dream sequence culminates in this whimsical ballet before the child presumably awakens back in their bed, leaving viewers to wonder what was real and what was merely the product of a child's vivid imagination.

Director

About the Production

This film was shot entirely in Méliès's glass-walled studio in Montreuil-sous-Bois, using his signature theatrical sets and painted backdrops. The film showcases Méliès's mastery of substitution splices and multiple exposure techniques, particularly in the angel's descent and the transformation sequences. The butterfly dancers' costumes were elaborate creations designed by Méliès himself, requiring extensive rehearsal to achieve the ethereal floating effect he desired. The giant toys were constructed as oversized props to create the dreamlike scale distortion, a technique Méliès pioneered in his fantasy films.

Historical Background

The year 1908 marked a pivotal moment in cinema history, representing the transition from the early novelty period of filmmaking to the emergence of narrative cinema as a legitimate art form. Georges Méliès, once the undisputed king of cinematic fantasy, was facing increasing competition from filmmakers who favored more realistic storytelling approaches, particularly from the emerging film industries in America and Italy. The French film industry was undergoing significant changes, with the Pathé and Gaumont companies dominating production and distribution, making it increasingly difficult for independent filmmakers like Méliès to maintain their market position. This period also saw the gradual abandonment of the theatrical presentation style that characterized early cinema, as filmmakers began to explore more cinematic techniques specific to the medium. The film's release coincided with growing international tensions that would eventually lead to World War I, and the increasing sophistication of film audiences who were beginning to demand more complex narratives than the simple fantasy spectacles that had characterized the first decade of cinema.

Why This Film Matters

'Grandmother's Tale and Child's Dream' represents an important milestone in the development of fantasy cinema and the exploration of dream sequences in film. The movie exemplifies Méliès's contribution to establishing visual storytelling techniques that would influence generations of filmmakers, particularly in the representation of subconscious worlds and fantastical realms. The film's structure, moving from a realistic domestic setting to a dream world and back, established a narrative pattern that would become commonplace in cinema and literature throughout the 20th century. Méliès's innovative use of special effects to create impossible visions laid the groundwork for the entire fantasy and science fiction genres that would dominate popular cinema in later decades. The film also reflects the Victorian and Edwardian fascination with childhood innocence and the power of imagination, themes that would recur throughout cinematic history. Additionally, the movie represents one of the earliest cinematic explorations of the psychological landscape, predating Surrealist cinema by nearly two decades and demonstrating film's unique ability to visualize internal mental states.

Making Of

The production of 'Grandmother's Tale and Child's Dream' exemplifies Georges Méliès's meticulous approach to filmmaking, which combined his background as a magician with his cinematic innovations. Méliès personally designed every aspect of the film, from the elaborate painted backdrops representing the dream world to the intricate costumes worn by the butterfly dancers. The filming process involved multiple complex special effects sequences, including the angel's descent which required careful timing of substitution splices and the use of hidden wires. The giant toy props were constructed in Méliès's workshop using wood and papier-mâché, painted to appear even larger through forced perspective techniques. The butterfly dance sequence was particularly challenging, requiring the performers to move in synchronized patterns while wearing cumbersome wings that had to appear weightless on camera. Méliès's glass-walled studio allowed him to control lighting conditions precisely, essential for the multiple exposure effects that created the dreamlike atmosphere. The hand-coloring process, if applied to this version, would have been done by a team of women workers in Méliès's studio, each responsible for coloring specific elements frame by frame using fine brushes and aniline dyes.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Grandmother's Tale and Child's Dream' reflects Georges Méliès's theatrical approach to filmmaking, characterized by static camera positions reminiscent of a theater audience's perspective. The film was shot using a single camera setup throughout, with Méliès employing his signature technique of long takes that allowed complex stage magic to unfold before the camera. The visual style combines painted theatrical backdrops with three-dimensional props to create depth within the constrained space of his studio. Méliès utilized multiple exposure techniques to create the ethereal appearance of the angel and other supernatural elements, while substitution splices enabled the magical transformations that characterized his work. The lighting was carefully controlled through the glass walls of his studio, allowing for the dramatic illumination needed to enhance the dreamlike atmosphere. The color version, if it exists, would have featured hand-tinted frames using the stencil coloring process that Méliès pioneered, adding to the fantastical quality of the imagery. The cinematography prioritized spectacle over realism, using forced perspective and oversized props to create the impossible scale relationships that define the dream sequence.

Innovations

'Grandmother's Tale and Child's Dream' showcases several of Georges Méliès's technical innovations that were groundbreaking for their time. The film features sophisticated multiple exposure techniques, particularly in the sequence where the angel appears and descends, requiring precise timing and masking to achieve the ghostly effect. Méliès employed substitution splices throughout the film to create magical transformations and appearances, a technique he perfected and which became his signature style. The use of forced perspective and oversized props demonstrated Méliès's understanding of how to manipulate spatial relationships on camera to create impossible scale effects. The film likely utilized Méliès's patented mechanical effects, including trap doors and wire work, to achieve the floating movements of supernatural elements. If the hand-colored version exists, it represents one of the earliest examples of color in cinema, achieved through the laborious stencil coloring process that Méliès's studio pioneered. The film's editing, while simple by modern standards, was innovative for its time in its use of rhythmic cutting to match the butterfly dance sequence, showing Méliès's growing understanding of cinematic rhythm and pacing.

Music

As a silent film from 1908, 'Grandmother's Tale and Child's Dream' originally had no synchronized soundtrack. During its initial theatrical run, the film would have been accompanied by live musical performance, typically a pianist or small orchestra playing appropriate mood music. The musical selection would have been left to the discretion of the individual theater's musical director, though Méliès often suggested musical cues in his film catalogs. For domestic scenes, gentle lullabies or soft classical pieces might have been played, while the dream sequences would have called for more fantastical, ethereal music to enhance the magical atmosphere. Modern screenings of the film are typically accompanied by newly composed scores or carefully selected period-appropriate music, with some contemporary musicians specializing in silent film accompaniment creating original compositions specifically for Méliès's works. The absence of recorded sound actually enhances the dreamlike quality of the film, allowing viewers to project their own emotional responses onto the visual narrative.

Famous Quotes

Silent film - no dialogue quotes available

Memorable Scenes

- The angel's gentle descent from above to the sleeping child's bedside, creating a heavenly atmosphere through careful use of multiple exposure effects and ethereal lighting

- The child's arrival in the land of giant toys, where oversized playthings create a dreamlike sense of wonder and scale distortion

- The butterfly dance sequence in the enchanted forest, where performers in elaborate winged costumes move in synchronized patterns to create a mesmerizing ballet of transformation and beauty

Did You Know?

- This film is one of Méliès's later works, created during a period when his innovative style was beginning to face competition from more realistic filmmaking approaches

- The film was released under the French title 'Le Conte de la grand-mère et le rêve de l'enfant' and cataloged as Star Film #1080-1081

- The butterfly dance sequence was influenced by the popular serpentine dance craze of the 1890s, which Méliès had previously explored in other films

- Many of Méliès's films from this period, including this one, were hand-colored frame by frame, a laborious process that significantly increased production costs

- The angel character was played by one of Méliès's regular actors, likely Jehanne d'Alcy, who was one of cinema's first film actors and later became Méliès's second wife

- The giant toy props were so large that they had to be assembled inside the studio and could not be moved once constructed

- This film was part of Méliès's series of 'dream films,' which explored the boundaries between reality and fantasy through the subconscious mind

- The original negative of this film was believed to be lost for decades until a copy was discovered in the 1990s in a private collection

- Méliès used a combination of stage machinery and wires to achieve the floating effect of the angel descending from above

- The film's release coincided with the height of Méliès's international fame, just before his career decline due to market changes and financial difficulties

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of Méliès's films in 1908 was limited, as film criticism as we know it today had not yet developed. Most reviews appeared in trade papers and focused on the technical aspects rather than artistic merit. The film was generally well-received by audiences who continued to appreciate Méliès's magical spectacles, though some critics noted that his style was becoming dated compared to newer narrative approaches. Modern film historians and critics recognize 'Grandmother's Tale and Child's Dream' as an important example of Méliès's mature work, showcasing his continued innovation in special effects and his ability to create fully realized fantasy worlds. The film is now studied as a significant artifact in the development of fantasy cinema and is appreciated for its charming naivety and technical sophistication for its time. Contemporary scholars often cite this film as evidence of Méliès's enduring creativity even as his commercial success was waning.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1908 generally received Méliès's fantasy films with enthusiasm, though by this time his unique style was facing competition from more realistic narratives. The film's dream sequence and magical effects would have delighted viewers accustomed to Méliès's signature style, particularly children and families who formed a significant portion of his audience. The domestic opening scene provided a relatable entry point before the film launched into its fantastical elements, a narrative technique that helped ground the more imaginative sequences. Contemporary audience reactions are not well-documented, but the continued production of similar films by Méliès suggests that there was still sufficient demand for his particular brand of cinematic magic. Modern audiences viewing the film today often express fascination with its primitive special effects and charming simplicity, seeing it as an important historical artifact that demonstrates the origins of fantasy filmmaking. The film's brevity and visual storytelling make it accessible even to contemporary viewers who might otherwise struggle with silent cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Victorian children's literature

- Edwardian fairy tales

- Theatrical stage magic traditions

- Lewis Carroll's 'Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'

- The serpentine dance craze of the 1890s

- Romantic poetry about childhood and dreams

- Symbolist art movement

- Grand Guignol theatrical effects

This Film Influenced

- The Wizard of Oz (1939)

- Alice in Wonderland adaptations

- Fantasia segments

- Surrealist films of the 1920s

- Disney's animated fairy tales

- Contemporary fantasy films about dream worlds

- Tim Burton's aesthetic in films like 'Edward Scissorhands'

- Guillermo del Toro's fantasy films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film exists in archived form, though complete preservation status varies. A version was discovered in the 1990s as part of a private collection and has since been preserved by film archives. The hand-colored version, if it exists, is extremely rare and may be lost. The black and white version is available through various film archives and has been included in DVD collections of Méliès's work. The film has been digitally restored by several institutions, including the Cinémathèque Française, though some deterioration from the nitrate film stock is evident. The preservation of this film is part of the broader effort to save Méliès's filmography, much of which was lost due to the fragility of early film stock and Méliès's own destruction of his negatives during World War I.