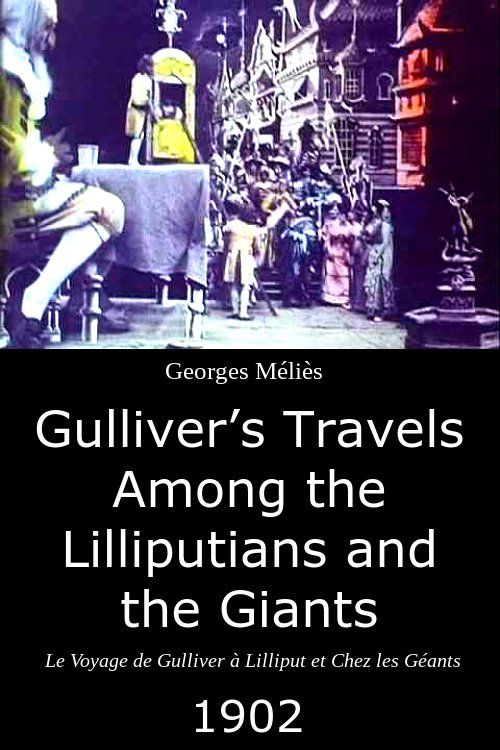

Gulliver's Travels Among the Lilliputians and the Giants

"The Marvelous Adventures of Gulliver Among Little People and Giants"

Plot

Georges Méliès' adaptation of Jonathan Swift's classic tale follows the adventures of Lemuel Gulliver, first in the land of Lilliput where he is a giant among miniature people, and then in the land of Brobdingnag where he becomes a tiny figure among enormous giants. The film showcases Gulliver's interactions with the Lilliputians, including being tied down by an army of tiny soldiers and observing their miniature society. In the land of giants, Gulliver experiences the opposite perspective, facing enormous creatures and objects that dwarf him completely. The narrative condenses Swift's extensive story into key visual spectacles, emphasizing the contrast in scale and the wonder of these fantastical worlds through Méliès' signature visual effects and theatrical presentation.

Director

Cast

About the Production

The film was hand-colored frame by frame using the stencil coloring method, an extremely labor-intensive process requiring dozens of workers to paint each individual frame. Méliès employed his trademark substitution splices, multiple exposures, and theatrical stage effects to create the illusion of size differences between Gulliver and the inhabitants of Lilliput and Brobdingnag. The production utilized oversized props and forced perspective photography to enhance the illusion of scale differences.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the golden age of early cinema, when Georges Méliès was one of the world's most innovative and successful filmmakers. 1902 was also the year Méliès released his most famous work, 'A Trip to the Moon,' establishing him as a pioneer of fantasy and science fiction cinema. The early 1900s saw rapid technological advancement in filmmaking, with the emergence of longer narrative films and more sophisticated special effects. Méliès' studio in Montreuil was producing hundreds of films annually, distributed globally through his Star Film Company. This period also marked the beginning of the film industry's transition from simple actualities to complex narrative fiction, with Méliès leading the way in establishing cinema as a medium for fantasy and spectacle. The hand-coloring technique used in this film represents an early attempt to bring color to motion pictures, decades before color film processes would become standard.

Why This Film Matters

Méliès' 'Gulliver's Travels' represents an important early adaptation of classic literature to the new medium of cinema, demonstrating how filmmakers approached well-known stories in the context of limited runtime and primitive technology. The film exemplifies Méliès' contribution to establishing fantasy as a viable genre in cinema, influencing countless future adaptations of Swift's work and other fantasy stories. Its hand-colored version serves as a testament to the early aspirations for color in cinema, showing that filmmakers from the very beginning sought to enhance visual storytelling beyond monochrome. The film also illustrates how Méliès' theatrical background shaped early cinematic language, with his use of painted backdrops, stage-like compositions, and direct address to the camera becoming foundational elements of film grammar. As one of the earliest literary adaptations, it helped establish the practice of bringing beloved books to the screen, a tradition that would become central to the film industry.

Making Of

The production of 'Gulliver's Travels' represented one of Méliès' most ambitious undertakings in terms of visual effects and color treatment. The hand-coloring process involved teams of women working in assembly-line fashion, with each worker responsible for coloring specific elements of each frame using stencils. This technique could take months for a single film. Méliès constructed elaborate sets in his glass studio in Montreuil, including detailed miniature landscapes for the Lilliput scenes and oversized furniture and props for the giant sequences. The film required careful choreography to maintain the illusion of scale differences, with actors positioned at precise distances from the camera. Méliès also employed his pioneering multiple exposure techniques to create scenes where Gulliver appears alongside the tiny Lilliputians. The production faced challenges in creating convincing size contrasts, leading Méliès to innovate with mirrors, glass paintings, and matte effects to enhance the visual spectacle.

Visual Style

The cinematography employs Méliès' characteristic theatrical style with static camera positions and tableau-like compositions that resemble stage presentations. The visual effects include substitution splices for magical appearances and disappearances, multiple exposures to create the illusion of different-sized characters sharing the same frame, and forced perspective using carefully constructed sets and props. The hand-coloring technique adds vibrancy to the visuals, with careful attention to costumes, sets, and special effects elements. The camera work includes innovative techniques for the time, such as the use of mirrors and glass paintings to enhance the illusion of scale. The cinematography emphasizes spectacle over realism, with bright colors, theatrical lighting, and stylized sets that create a fantastical atmosphere appropriate to the story.

Innovations

The film showcases several technical innovations for its time, including sophisticated use of forced perspective to create convincing size differences between characters. The hand-coloring process using stencils represented a significant technical achievement, requiring meticulous frame-by-frame painting. Méliès employed multiple exposure techniques to combine actors of different apparent sizes in the same shot. The production utilized elaborate mechanical effects and trap doors in the stage floor to create magical appearances and disappearances. The film also demonstrates Méliès' mastery of substitution splices and in-camera effects that would influence generations of filmmakers. The miniature sets and oversized props required innovative construction techniques to achieve the desired visual effects.

Music

As a silent film, it would have been accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical exhibitions. Typical accompaniment might have included piano or small ensemble music, often using popular classical pieces or improvised melodies that matched the on-screen action. The hand-colored versions of the film might have been accompanied by more elaborate musical arrangements to match their enhanced visual presentation. No original score was composed specifically for the film, as was common practice during this period of cinema.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, it contains no spoken dialogue, but intertitles would have included narrative explanations such as 'Gulliver arrives in the land of Lilliput' and 'The tiny people tie down the sleeping giant'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening scene where Gulliver awakens to find himself tied down by hundreds of tiny Lilliputian soldiers

- The sequence showing Gulliver towering over the miniature city of Lilliput, with tiny soldiers marching around him

- The dramatic contrast when Gulliver appears as a tiny figure in the land of giants, dwarfed by enormous furniture and people

- The card-playing scene that recreates Méliès' earlier work with size-based humor

- The final scenes showing Gulliver's departure from the fantasy lands, utilizing Méliès' signature disappearing effects

Did You Know?

- The film features a remake of Méliès' earlier 1896 film 'Une partie de cartes' (A Game of Cards), showing how he incorporated and improved upon his previous works

- Hand-coloring of films in 1902 was so expensive and time-consuming that only a few copies were typically produced, making colored versions extremely rare

- The missing shipwreck scene was described in contemporary catalogs but has been lost from surviving prints

- Méliès himself plays the role of Gulliver, as was common for his films where he often starred as the protagonist

- The film was cataloged as Star Film #433 in Méliès' production list

- Some versions of the film were tinted rather than fully hand-colored, showing different levels of color treatment

- The giant sequences required Méliès to be filmed through a miniature set with oversized props to create the illusion of his small size

- The Lilliputian soldiers were played by children and Méliès' regular troupe of actors using forced perspective techniques

- The film was distributed internationally, with versions shown in the United States through the Edison Manufacturing Company

- Contemporary advertisements emphasized the film's spectacular visual effects and the novelty of seeing Swift's famous story brought to life

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's visual ingenuity and clever special effects, with trade publications noting particularly the convincing illusion of size differences between Gulliver and the inhabitants of the different lands. The hand-colored version received special attention for its vibrant appearance, with reviewers marveling at the technical achievement of color in motion pictures. Modern critics and film historians recognize the work as an important example of early fantasy cinema and Méliès' mastery of visual effects. While some note the film's narrative simplicity compared to Swift's original work, most acknowledge that this was typical of adaptations of the period, which focused on visual spectacle rather than literary fidelity. The film is now studied as an example of how early filmmakers approached literary adaptation and as a showcase of Méliès' technical innovations.

What Audiences Thought

The film was popular with audiences of its time, who were fascinated by the visual effects and the novelty of seeing a familiar story brought to life through the magic of cinema. Contemporary reports indicate that audiences particularly enjoyed the scenes with the Lilliputian soldiers and the contrast between the tiny people and the giant Gulliver. The hand-colored versions were especially prized by exhibitors and audiences alike, commanding higher ticket prices due to their rarity and visual appeal. The film's success contributed to Méliès' reputation as a master of cinematic fantasy and helped establish the commercial viability of literary adaptations. Modern audiences viewing the film in retrospectives and archives continue to be impressed by the creativity of the visual effects and the historical significance of the work, even as the narrative simplicity reflects the limitations of early cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Jonathan Swift's 1726 novel 'Gulliver's Travels'

- Méliès' own 1896 film 'Une partie de cartes'

- Contemporary stage magic and theatrical traditions

- Lumière Brothers' early actualities

- Popular illustrated editions of Swift's work

This Film Influenced

- Later adaptations of 'Gulliver's Travels' including the 1939 animated version and various live-action remakes

- Other early fantasy films dealing with size differences such as 'The Incredible Shrinking Man'

- The development of special effects techniques in fantasy cinema

- The tradition of literary adaptations in cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in both black-and-white and hand-colored versions, though some scenes including the original shipwreck sequence are believed to be lost. Prints are held in several major film archives including the Cinémathèque Française, the Museum of Modern Art, and the British Film Institute. The hand-colored version is particularly rare due to the limited number of colored copies originally produced. Some restoration work has been done on surviving prints, but the film shows the deterioration typical of early nitrate film stock.