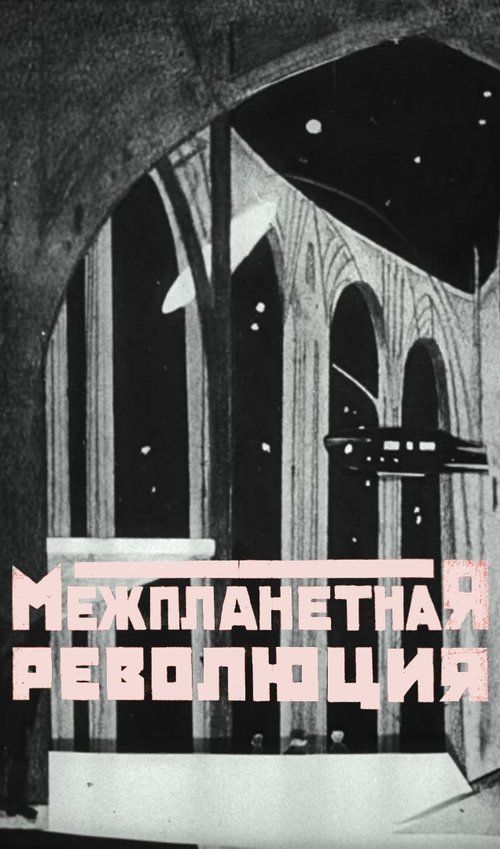

Interplanetary Revolution

Plot

Interplanetary Revolution depicts the desperate flight of international capitalists portrayed as parasitic bloodsuckers who cannot escape the spreading Soviet revolution on Earth. Gathering their ill-gotten wealth, these bourgeois elements construct rockets and flee into outer space, believing they can escape the workers' uprising. However, the revolutionary proletariat, representing the Soviet working class, pursues them across the cosmos in their own spacecraft, demonstrating that the revolution knows no boundaries. The film culminates with the capitalists receiving their inevitable punishment even in the far reaches of space, symbolizing that no distance can shield oppressors from revolutionary justice. This cosmic chase serves as an allegory for the inevitability of socialist victory and the futility of capitalist resistance.

Director

About the Production

Created using cut-out animation techniques with paper figures, typical of early Soviet animation. The film was produced during the early years of Soviet cinema when animation was still experimental. The production likely faced severe material shortages common in the early Soviet period, requiring creative solutions for materials and equipment. The animators used primitive techniques including paper cut-outs and possibly early forms of stop-motion to create the space sequences.

Historical Background

Interplanetary Revolution was created in 1924, during Lenin's New Economic Policy period and just two years after the formal establishment of the Soviet Union. This was a time when the Soviet government was actively developing cinema as a tool for political education and mass communication. The film reflects the aggressive revolutionary fervor of the early Soviet period, when the Bolsheviks believed that world revolution was imminent and inevitable. The early 1920s saw the emergence of Soviet avant-garde art, with filmmakers experimenting with new techniques and forms of expression. Animation was in its infancy worldwide, and Soviet animators were developing their own distinct style that would later influence animation globally. The film's space theme was particularly prescient, coming decades before the Space Race and reflecting the Soviet fascination with scientific progress and technological advancement as tools for building socialism.

Why This Film Matters

Interplanetary Revolution represents a crucial early example of how animation was used for political propaganda in the Soviet Union, establishing patterns that would influence Soviet animation for decades. The film demonstrates how the new Soviet state adapted emerging artistic mediums to serve revolutionary purposes, a practice that would become central to Soviet cultural policy. Its use of science fiction elements for political messaging was innovative and would later be echoed in numerous Soviet works. The film also illustrates the early Soviet belief in the universality of communist revolution, extending even to the cosmos. As one of the earliest examples of animated science fiction, it predates many more famous works in the genre and shows how quickly filmmakers recognized the potential of animation for depicting fantastic scenarios impossible to film in live-action. The film's survival makes it an invaluable document of early Soviet animation techniques and political messaging.

Making Of

Interplanetary Revolution was created during the formative years of Soviet cinema when the new government was actively using film as a tool for political education and propaganda. The animation team, led by Youry Merkulov, worked with extremely limited resources in post-revolutionary Russia, where materials were scarce and technical equipment was primitive. The animators likely used paper cut-outs and simple stop-motion techniques to create the moving figures, with backgrounds painted by hand. The space sequences would have been particularly challenging, requiring innovative approaches to depict zero gravity and spacecraft movement. The film was probably produced in a small workshop rather than a proper studio, reflecting the makeshift nature of early Soviet film production. The political message was paramount, with visual symbolism taking precedence over technical sophistication or narrative subtlety.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Interplanetary Revolution would have been extremely basic by modern standards, reflecting the technical limitations of early Soviet animation. The film likely used static camera positions with the animated action occurring within a fixed frame. The space sequences would have employed simple techniques to suggest movement and zero gravity, possibly including wire work for the paper cut-outs and painted backgrounds suggesting cosmic environments. The visual style would have been highly symbolic rather than realistic, with characters rendered in exaggerated forms to emphasize their class identities. The animation technique was primarily cut-out animation, with paper figures moved frame by frame against painted backgrounds. The film's visual aesthetic reflects the constructivist influence common in early Soviet art, with bold geometric shapes and strong contrasts.

Innovations

While technically primitive by modern standards, Interplanetary Revolution represented several achievements for its time and place. The film demonstrated early Soviet animators' ability to create complex narratives using limited cut-out animation techniques. The space sequences were particularly innovative for 1924, showing early attempts to depict zero gravity and spacecraft movement in animation. The film's use of symbolic visual language to convey complex political ideas was sophisticated for early animation. The production team's ability to create any animated content under the severe material shortages of post-revolutionary Russia was itself a significant achievement. The film also represents an early example of using animation for science fiction themes, predating many more famous works in both animation and science fiction cinema.

Music

Interplanetary Revolution was created as a silent film, as synchronized sound technology would not be introduced to cinema for several more years. During original screenings, the film would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small orchestra playing appropriate pieces. The musical accompaniment would likely have included popular revolutionary songs of the period and classical pieces chosen to match the on-screen action. In some Soviet venues, the film might have been accompanied by a narrator explaining the political message, as literacy was still limited in the early Soviet period. Modern screenings of the film typically use period-appropriate musical accompaniment or newly composed scores that attempt to capture the revolutionary spirit of the original context.

Famous Quotes

No quote data available for this silent film

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic sequence where capitalists board rockets to escape Earth, their paper cut-out figures climbing ladders to primitive spacecraft while workers watch from below

- The cosmic chase scene where proletarian rockets pursue the capitalist vessels through painted space, with simple animation suggesting movement among stars and planets

- The final confrontation in space where workers deliver justice to the fleeing capitalists, likely depicted through symbolic visual metaphors rather than literal violence

Did You Know?

- This is one of the earliest surviving examples of Soviet animated cinema, created just two years after the USSR's formation

- The film predates famous Soviet animated works like 'The New Gulliver' (1935) by over a decade

- Director Youry Merkulov was among the pioneers of Soviet animation, though little is known about his other works

- The space theme was remarkably forward-thinking for 1924, coming before the space race and even before early sci-fi classics like 'Metropolis' (1927)

- The film uses cut-out animation, a technique that would remain popular in Soviet animation for decades

- The portrayal of capitalists as literal bloodsuckers reflects the aggressive propaganda style of early Soviet cinema

- This film represents an early example of science fiction being used for political propaganda

- The animation was likely created without sound, as synchronized sound technology wouldn't arrive in cinema for several more years

- Very few copies of this film are known to exist, making it an extremely rare piece of cinematic history

- The film's space sequences were created using simple special effects, possibly including multiple exposure techniques

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of Interplanetary Revolution is largely undocumented, as it was primarily shown as propaganda rather than as entertainment. Soviet critics of the period likely evaluated it based on its political effectiveness rather than artistic merit. Modern film historians recognize the film as an important artifact of early Soviet animation, though it is rarely discussed in detail due to its rarity. Scholars of propaganda cinema note it as an example of how the Soviet state quickly adapted new artistic forms to political purposes. Animation historians acknowledge it as a pioneering work, though technically primitive compared to later Soviet masterpieces. The film is generally appreciated today more for its historical significance than its artistic achievements, serving as a window into the early development of both Soviet animation and political cinema.

What Audiences Thought

The original audience reception of Interplanetary Revolution is not well documented, as it was primarily shown to workers and soldiers as part of political education programs rather than to general cinema audiences. Soviet viewers of the 1920s would have been familiar with the film's aggressive political messaging and symbolic portrayal of class enemies. The space elements would have been particularly novel and impressive to audiences of the era, few of whom had seen any form of science fiction in cinema. Modern audiences viewing the film today primarily encounter it in archival screenings or academic contexts, where it is appreciated for its historical value rather than entertainment. The film's primitive animation style and overt propaganda make it challenging for contemporary viewers to engage with as entertainment, though it remains fascinating as a historical artifact.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet propaganda art

- Constructivist design

- Political posters

- Revolutionary literature

- Early science fiction literature

- Political cartoons

This Film Influenced

- Later Soviet propaganda animations

- Science fiction propaganda films

- Political animated shorts

- Cosmic-themed revolutionary art

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Extremely rare - only a few copies are known to exist in film archives, primarily in Russian and Eastern European collections. The film is considered partially preserved but deteriorating, with some sequences possibly lost or severely damaged. Restoration efforts have been limited due to the film's obscurity and the technical challenges of preserving early animation. The film exists as an important but fragile artifact of early Soviet cinema history.