Krazy Kat Goes A-Wooing

Plot

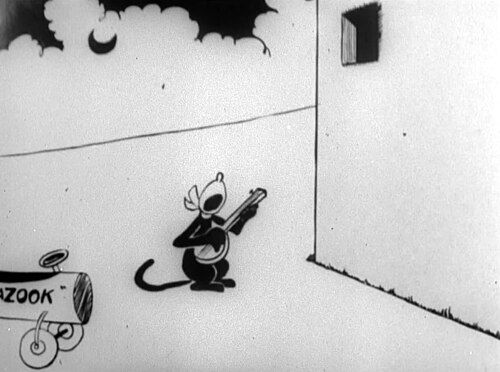

In this silent animated short, the lovestruck Krazy Kat attempts to win the affection of Ignatz Mouse through romantic serenading and persistent courtship. Krazy Kat follows Ignatz around, trying to serenade him with various musical instruments and romantic gestures, much to Ignatz's annoyance. The mouse, as always, responds not with affection but with his trademark brick-throwing, which Krazy misinterprets as expressions of love. Officer Pupp makes appearances to protect Krazy from Ignatz's attacks, adding to the comedic chaos. The cartoon follows the classic Krazy Kat formula of unrequited love, misunderstanding, and slapstick violence that defined the comic strip's charm.

About the Production

This was one of the earliest animated adaptations of George Herriman's popular comic strip. The animation was created using the cut-out technique rather than traditional cel animation, which was still in its infancy. The production team worked under the supervision of William Randolph Hearst's animation studio, which was primarily focused on adapting his newspaper comic properties to the screen. The soundtrack would have been provided live in theaters by pianists or small orchestras, following the standard practice of the silent era.

Historical Background

1916 was a pivotal year in early American animation, occurring just as the industry was transitioning from simple novelties to more sophisticated storytelling. The United States was in the midst of World War I (though it wouldn't enter until 1917), and films served as both entertainment and propaganda. Animation was still finding its artistic voice, with pioneers like Winsor McCay, Raoul Barré, and Earl Hurd developing the techniques that would define the medium. The newspaper comic strip was at the height of its popularity as a mass medium, and publishers like William Randolph Hearst were eager to capitalize on their popular characters by adapting them to the new medium of film. This period saw the establishment of the first dedicated animation studios and the development of foundational techniques like cel animation, which would revolutionize the industry in the coming years.

Why This Film Matters

Krazy Kat Goes A-Wooing represents an important milestone in the history of animation as one of the earliest attempts to adapt a sophisticated comic strip to the screen. George Herriman's Krazy Kat was beloved by intellectuals and artists for its surreal humor, poetic language, and exploration of themes like unrequited love and the nature of reality. While the animated versions simplified the strip's complex themes, they helped introduce these characters to a broader audience who might not have read the comics. The film is part of the larger story of how animation evolved from simple mechanical amusements to a legitimate artistic medium capable of expressing complex emotions and ideas. The enduring popularity of the Krazy Kat-Ignatz dynamic influenced countless later animated relationships, particularly the trope of the lovestruck pursuer and the reluctant beloved.

Making Of

The production of Krazy Kat Goes A-Wooing took place during the pioneering days of American animation, when the medium was still establishing its artistic and commercial foundations. The animators at International Film Service worked under challenging conditions, using rudimentary equipment and experimental techniques. The cut-out animation method involved creating paper cutouts of the characters and moving them frame by frame against background drawings, a laborious process that required immense patience. The voice of Krazy Kat was provided through intertitles rather than dialogue, as was standard for silent films. The production team had to adapt Herriman's highly stylized comic strip art to the limitations of early animation, resulting in simplified character designs that could be more easily animated. The studio operated under the commercial pressure of producing content quickly and cheaply for the growing demand for animated shorts in theater programs.

Visual Style

The visual style of Krazy Kat Goes A-Wooing reflects the technical limitations and aesthetic conventions of early animation. The film uses static camera angles typical of the period, with the action taking place within a single frame without camera movement. The animation employs the cut-out technique, giving the characters a distinctive flat, paper-like quality that differs from both the comic strip's line art and later cel animation. The backgrounds are simple and stylized, designed to be quickly produced and easily recognizable. The black and white cinematography uses high contrast to ensure the characters stand out clearly against their backgrounds, a necessity given the primitive projection equipment of the era. The visual humor relies on exaggerated movements and clear, simple gestures that could be easily understood without dialogue.

Innovations

While Krazy Kat Goes A-Wooing may appear primitive by modern standards, it represented several technical achievements for its time. The use of cut-out animation, though labor-intensive, allowed for more complex movements than the earlier flip-book style animations. The production team developed techniques for creating the illusion of depth and movement within a two-dimensional space. The film demonstrates early experiments in character animation, with attempts to give the characters personality through their movements and expressions. The synchronization of action with musical accompaniment, though not recorded, shows an understanding of the importance of rhythm and timing in animation. The adaptation of comic strip characters to animation required solving technical challenges in character design and movement that would influence later animated adaptations of comic properties.

Music

As a silent film, Krazy Kat Goes A-Wooing had no recorded soundtrack. The musical accompaniment would have been provided live in theaters, typically by a pianist playing from cue sheets or improvising based on the action on screen. The music would have followed the conventions of silent film accompaniment, using popular songs of the era, classical pieces, and original improvisations to match the mood of each scene. For the serenading sequences, the pianist might have played romantic popular songs of the period, while the slapstick brick-throwing scenes would have been accompanied by comedic, fast-paced music. Some larger theaters might have employed small orchestras or organists to provide more elaborate accompaniment. The lack of synchronized sound meant that the music could vary significantly from theater to theater and from performance to performance.

Memorable Scenes

- Krazy Kat's elaborate serenade attempts using various musical instruments while following an increasingly annoyed Ignatz Mouse

- The classic brick-throwing sequence where Ignatz hurls a brick at Krazy, who interprets it as a sign of affection

- Officer Pupp's intervention to protect Krazy from Ignatz's attacks, adding to the chaotic comedy

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first animated adaptations of George Herriman's Krazy Kat comic strip, which began in 1913

- The film was produced by William Randolph Hearst's International Film Service, which specialized in adapting newspaper comics

- George Herriman, the creator of Krazy Kat, had limited direct involvement in these early animated adaptations

- The animation technique used was primarily cut-out animation, which was faster and cheaper than the emerging cel animation process

- Krazy Kat's gender was deliberately ambiguous in both the comic strip and early animations, adding to the character's surreal charm

- The brick-throwing gag that defines the Krazy Kat-Ignatz relationship originated in the comic strip and became a staple in the animated versions

- This short was likely distributed as part of a larger program of animated shorts and live-action comedies in theaters

- The character designs in this early adaptation differed significantly from later versions and Herriman's original artwork

- Silent era audiences would have experienced this film with live musical accompaniment, typically provided by a theater pianist

- The success of these early Krazy Kat cartoons helped establish the viability of adapting newspaper comics to animation

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception for animated shorts in 1916 was minimal, as animation was not yet considered a serious art form worthy of substantial critical attention. Trade publications like Variety and Moving Picture World would have mentioned the film briefly in their coverage of theater programs, typically noting it as a novelty item. Modern film historians and animation scholars view these early Krazy Kat cartoons as historically significant artifacts, though they acknowledge that they lack the artistic sophistication of Herriman's original comic strip. Critics today appreciate these shorts as important examples of early American animation and as evidence of how comic strip characters were first adapted to the screen, even while recognizing their technical and narrative limitations.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception for Krazy Kat Goes A-Wooing in 1916 would have been largely positive, as animated shorts were popular novelties that provided comic relief between longer live-action features. Theater audiences of the silent era enjoyed the simple visual humor and the familiarity of characters they knew from newspaper comics. The brick-throwing gags and slapstick violence would have been particularly appealing to audiences of the time. However, the sophisticated philosophical themes that made the comic strip beloved by intellectuals were largely lost in translation to the animated format. Modern audiences encountering the film today often find it charming as a historical artifact, though it may seem primitive compared to later animation.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- George Herriman's Krazy Kat comic strip

- Earlier comic strip adaptations by International Film Service

- Silent era slapstick comedies

- Vaudeville performance traditions

This Film Influenced

- Later Krazy Kat animated series

- Other comic strip adaptations of the 1920s and 1930s

- Theatrical animated shorts featuring animal characters

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of Krazy Kat Goes A-Wooing is uncertain, as many animated shorts from this period have been lost due to the unstable nitrate film stock used in the 1910s. Some early Krazy Kat cartoons survive in film archives and private collections, while others exist only in fragments or are considered lost films. The Library of Congress and other preservation institutions hold some International Film Service productions, but specific information about this particular title's survival is limited. Film historians continue to search for lost animated works from this pioneering era of American animation.