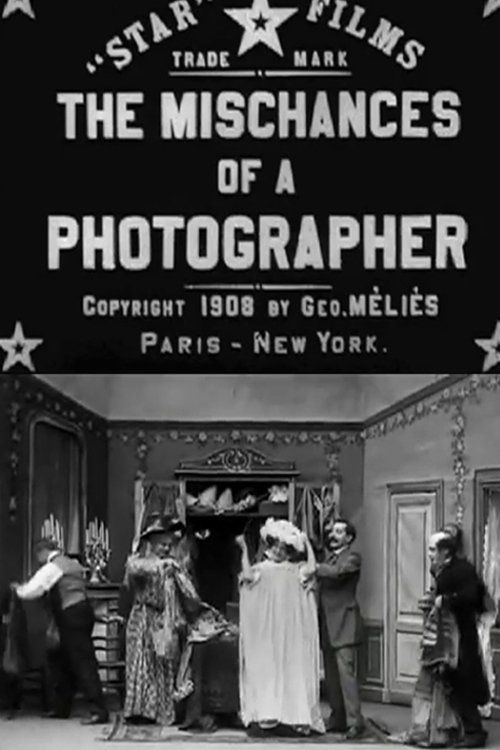

Les malheurs d'un photographe

Plot

A well-dressed family arrives at a photographer's studio for a portrait session. The pompous photographer, dressed in formal attire, immediately begins mistreating the young boy in the family, pushing him around and treating him roughly while the parents remain oblivious or unconcerned. The photographer attempts to pose the family for their photograph, but his abusive behavior toward the child continues throughout the session. After enduring repeated mistreatment, the clever young boy devises a series of revenge schemes against the photographer, using his wits to turn the tables on his tormentor. The film culminates in chaotic comedic scenes where the photographer receives his comeuppance through the boy's ingenious tricks and pranks.

Director

About the Production

Like most Méliès films from this period, it was shot in his glass-walled studio in Montreuil using theatrical sets and props. The film featured Méliès' signature use of substitution splices and multiple exposure techniques to create magical effects and comedic gags. The photographer character was likely played by Méliès himself, as he often appeared in his own films.

Historical Background

1908 was a pivotal year in cinema history, occurring during the transition from the 'cinema of attractions' to narrative storytelling. The film industry was rapidly professionalizing, with companies like Pathé and Gaumont dominating the market. Méliès, once a leading figure, was facing increasing competition and changing audience tastes. This period saw the rise of longer narrative films and the decline of the short trick films that had made Méliès famous. The film reflects the social norms of the Belle Époque era, when photography was becoming more accessible to the middle class and professional photographers held a certain status in society. The theme of a child outsmarting an adult authority figure resonated with contemporary audiences and reflected changing attitudes about childhood and discipline.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents Méliès' contribution to the development of comedy in early cinema, particularly the theme of revenge comedy that would become a staple of film humor. It demonstrates how Méliès adapted his magical filmmaking techniques to more grounded, realistic scenarios while maintaining his distinctive visual style. The film is part of the broader tradition of early cinema exploring modern professions and social situations, helping to establish the comedy of manners in film. It also shows the evolution of child characters in cinema from mere props to active agents with their own agency. The film's focus on photography as a subject is particularly meta, as cinema and photography were competing and complementary visual media during this period.

Making Of

The film was created in Méliès' glass studio in Montreuil, which allowed for natural lighting while maintaining complete control over the filming environment. Méliès, who had a background in theater and magic, designed and built all the sets himself. The photographer's studio set would have been constructed to resemble a typical early 20th-century photography studio with period-appropriate props and backdrops. The film likely employed Méliès' innovative editing techniques, including substitution splices for the revenge sequences. As with many of his films, Méliès probably directed, produced, wrote, and starred in the production. The hand-coloring process, if used, would have been done by women workers at his studio using elaborate stencil systems, with each color applied separately.

Visual Style

The film employs Méliès' characteristic static camera positioning, typical of early cinema where the camera functioned like a theatrical audience member. The framing is likely medium shots to capture the full action and interactions between characters. The lighting would have been natural sunlight from the glass studio, supplemented by artificial lighting when needed. The black and white cinematography features the high contrast typical of the period. If hand-colored prints existed, they would feature selective coloring of important elements, a Méliès trademark that added visual interest and highlighted key props or costumes.

Innovations

The film showcases Méliès' mastery of substitution splices for creating magical transformations and visual gags, particularly in the revenge sequences. His use of multiple exposure techniques allows for the appearance of ghostly or impossible images. The film demonstrates sophisticated editing for its time, with carefully timed cuts to enhance comedic effect. Méliès' innovative use of theatrical sets painted to create depth and perspective within the flat photographic space represents an important technical achievement in early film production. The film also exhibits Méliès' pioneering work in creating continuous narrative action within a single, theatrical space.

Music

As a silent film from 1908, it had no synchronized soundtrack. During exhibition, it would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small ensemble in theaters. The musical accompaniment would have been improvised or chosen from existing classical pieces to match the on-screen action and mood. For the comedic scenes, lively, upbeat music would have been played, while more dramatic moments might have featured contrasting musical themes. The exact musical selections would have varied by theater and musician.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where the family enters the photographer's studio and the photographer immediately begins his mistreatment of the young boy

- The series of revenge pranks the boy executes against the photographer using clever tricks and visual effects

- The final chaotic scene where the photographer receives his ultimate comeuppance through the boy's elaborate scheme

Did You Know?

- This film is one of Méliès' later works from his most productive period (1902-1912)

- The title translates to 'The Misfortunes of a Photographer' or 'The Photographer's Misfortunes'

- Like many Méliès films, it was likely hand-colored in some prints using stenciling techniques

- The film was released by Star Film Company and cataloged as number 1236-1238

- Méliès frequently explored themes of authority figures getting their comeuppance in his comedies

- The photographer character was a common comedic archetype in early cinema

- This film showcases Méliès' transition from pure fantasy to more grounded comedic situations

- The film was likely shot on 35mm film with Méliès' custom camera setup

- It represents one of Méliès' shorter works from this period, as his films were getting progressively longer

- The film demonstrates Méliès' continued use of theatrical staging even in more realistic scenarios

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception for this specific film is not well-documented, as film criticism was still in its infancy in 1908. However, Méliès' films from this period were generally well-received by audiences who appreciated his visual inventiveness and humor. Modern film historians and scholars recognize this work as an example of Méliès' later period, showing his adaptation to changing cinematic tastes while maintaining his unique approach to visual comedy. The film is valued today as part of Méliès' extensive oeuvre and as an example of early narrative comedy development.

What Audiences Thought

Early 20th-century audiences generally enjoyed Méliès' comedies, particularly those featuring clever children outsmarting pompous adults. The revenge theme would have resonated with viewers of all ages, providing satisfying comic justice. The film's visual gags and slapstick elements were popular entertainment forms of the era. As with many of Méliès' shorter works, it would have been shown as part of a varied program of short films, offering audiences a brief but entertaining experience. The relatable scenario of a family photo session, combined with the exaggerated comedy, made it accessible to a broad audience.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage magic traditions

- Comédie-Française theatrical style

- French vaudeville

- Early photography culture

- Georges Méliès' own magical films

This Film Influenced

- Later revenge comedies

- Child protagonist films

- Photography-themed movies

- Early slapstick comedies

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in various film archives, including the Cinémathèque Française. Some prints exist in black and white, while others may have hand-coloring. The film has been digitally restored as part of various Méliès collections and is available through specialized film archives and some home video releases.