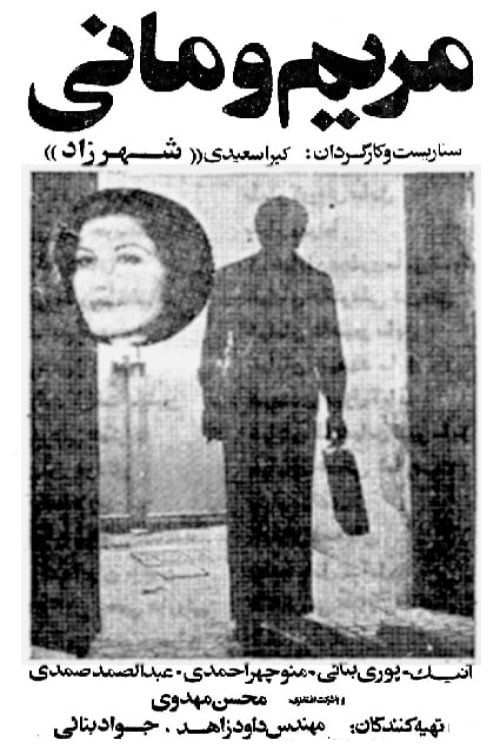

Maryam and Mani

"A love story that challenged a nation on the brink of revolution"

Plot

Maryam and Mani is a poignant Iranian drama that explores the complex relationship between two young lovers from different social backgrounds in pre-revolutionary Iran. Maryam, a woman from a wealthy and traditional family, falls deeply in love with Mani, a humble and idealistic poet from the working class. Their forbidden romance faces numerous obstacles, including family opposition, societal expectations, and the political turmoil brewing in 1970s Iran. As their relationship unfolds, the film delves into themes of class struggle, personal freedom, and the transformative power of love. The narrative reaches an emotional climax when the couple must make a heart-wrenching decision that will alter their lives forever. Set against the backdrop of a society on the brink of revolution, their personal story becomes a metaphor for the larger social changes occurring in Iran.

About the Production

Filmed during the final years of the Pahlavi dynasty, capturing a unique moment in Iranian society. The production faced challenges from both government censors and conservative elements due to its critical portrayal of class divisions. Director Shahrzad, one of Iran's pioneering female directors, had to navigate complex political sensitivities to bring this story to the screen. The film was completed just months before the Iranian Revolution, which would dramatically alter the country's film industry.

Historical Background

Maryam and Mani was produced during one of the most turbulent periods in Iranian history. 1978 was the year of massive popular uprising against the Shah's regime, with strikes, demonstrations, and clashes becoming increasingly common. The film captures this pivotal moment when Iranian society was in transition, with traditional values clashing against modernization and Western influence. Cinema in Iran at this time was experiencing its own revolution, with a new wave of filmmakers creating more socially conscious works that reflected the growing discontent among the population. The film's release just months before the revolution meant it was one of the last artistic products of the Pahlavi era, making it a valuable historical document of pre-revolutionary Iranian culture and society. The subsequent banning of the film by the new Islamic regime reflected the dramatic shift in cultural politics that followed the revolution.

Why This Film Matters

Maryam and Mani holds a unique place in Iranian cinema as both an artistic achievement and a historical artifact. As one of the few Iranian films directed by a woman in the 1970s, it represents an important milestone for female filmmakers in the country. The film's unflinching look at class divisions and social inequality was groundbreaking for its time, paving the way for more politically engaged cinema in Iran. Its preservation and restoration in the 2010s sparked renewed interest in pre-revolutionary Iranian cinema among scholars and film enthusiasts. The film has been studied extensively for its portrayal of Tehran on the eve of revolution, serving as a visual record of a society that would soon be transformed. Contemporary Iranian filmmakers often cite Maryam and Mani as an influence, particularly in how it balanced personal storytelling with social commentary. The film's themes of love transcending social boundaries continue to resonate with audiences today, making it a timeless classic beyond its historical significance.

Making Of

The making of Maryam and Mani was fraught with challenges from its inception. Director Shahrzad fought for years to secure funding for the project, as many investors were hesitant to back a film with such overt social commentary. The casting process was particularly difficult, as several established actors refused to work with a female director or participate in a film that criticized Iranian society. The breakthrough came when Manoucher Ahmadi, a respected theater actor, agreed to play Mani, which in turn attracted Pouri Banaei to the project. Filming took place over 47 days in the sweltering summer of 1978, with the crew often working around spontaneous political demonstrations that would erupt in Tehran. The most challenging scene to film was the protest sequence, which required hundreds of extras and nearly resulted in the production being shut down by authorities. Despite these obstacles, the cast and crew formed a tight bond, with many describing the experience as creating 'art in the eye of the storm' as the revolution approached.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Maryam and Mani, handled by renowned cinematographer Nasser Taghvai, is characterized by its naturalistic style and innovative use of Tehran's urban landscape. Taghvai employed handheld cameras for many intimate scenes between the lovers, creating a sense of immediacy and authenticity that was groundbreaking for Iranian cinema at the time. The film's visual language contrasts the opulent interiors of Maryam's world with the gritty streets of Mani's neighborhood, using lighting and composition to emphasize class differences without being heavy-handed. The color palette shifts throughout the film, moving from warm golden tones during the couple's happiest moments to cold blues and grays as political tensions rise. Taghvai's use of reflection—showing characters in mirrors, windows, and puddles—creates a visual motif about identity and perception. The film's most celebrated sequence is a long tracking shot through a Tehran marketplace during a protest, which was technically ambitious for its time and remains a masterclass in capturing chaos with grace.

Innovations

Maryam and Mani featured several technical innovations for Iranian cinema of its era. The film was among the first in Iran to use synchronous sound recording for location shooting, allowing for more authentic dialogue and ambient sounds. Director Shahrzad employed jump cuts and non-linear narrative techniques that were influenced by European art cinema but relatively new to Iranian audiences. The production team developed new methods for filming crowd scenes without drawing attention from authorities, using hidden cameras and long lenses to capture authentic street life. The film's color grading process was particularly sophisticated for the time, using a new German-developed technique to create subtle tonal shifts that reflected the emotional journey of the characters. The restoration project in 2010 utilized cutting-edge digital technology to repair damage to the original negative while preserving the film's unique visual aesthetic. This restoration won technical awards for its innovative approach to preserving and enhancing vintage film stock without compromising the original artistic vision.

Music

The musical score for Maryam and Mani was composed by legendary Iranian musician Mohammad-Reza Darvishi, who blended traditional Persian instruments with Western orchestral arrangements to create a sound that reflected the film's themes of cultural transition. The soundtrack features prominently the setar and santur, which represent Mani's connection to traditional Persian culture, while subtle strings and piano accompany Maryam's world of modernity. One of the most memorable pieces is the 'Love Theme,' a haunting melody played on the ney flute that recurs throughout the film during key emotional moments. The soundtrack also includes period-appropriate pop songs that play on radios in background scenes, helping to establish the film's 1970s setting. Darvishi's score was so well-regarded that it was released as a separate album, becoming a bestseller in Iran before the revolution. The music was partially lost with the film's negative, but Darvishi had kept detailed notes and was able to reconstruct the score for the 2010 restoration.

Famous Quotes

Maryam: 'In your poems, I see a world that could be. In my world, I see only what must be.'

Mani: 'They say love cannot bridge the distance between our worlds. I say love is the only bridge that matters.'

Maryam's father: 'Honor is heavier than love, daughter. Remember this when your heart leads you astray.'

Mani: 'I write poetry not because I have the words, but because I have the feeling that needs them.'

Maryam: 'In Tehran, every street corner holds a revolution. In your arms, I found my own.'

Memorable Scenes

- The rooftop scene where Mani recites poetry to Maryam as the sun sets over Tehran, with the city's minarets and modern buildings silhouetted against the orange sky. This moment encapsulates the film's themes of tradition meeting modernity, and features some of the most poetic dialogue in Iranian cinema.

- The clandestine meeting in the Grand Bazaar where Maryam and Mani exchange letters while navigating through crowds of protesters, their personal drama playing out against the backdrop of growing political unrest.

- The emotional confrontation at Maryam's family mansion where she must choose between her family's expectations and her love for Mani, featuring powerful performances from both leads in a scene that builds to a heartbreaking climax.

Did You Know?

- This was director Shahrzad's second feature film and is considered her most significant work

- The film was banned in Iran after the 1979 Revolution due to its depiction of pre-revolutionary society

- Manoucher Ahmadi and Pouri Banaei were rumored to be in a real-life relationship during filming

- The original negative was believed lost during the revolution but was discovered in a film archive in Paris in 2005

- The poem Mani recites in the film was written by contemporary Iranian poet Forough Farrokhzad

- The film's premiere was attended by Princess Ashraf Pahlavi, the Shah's twin sister

- Only 12 copies of the film were known to exist before the restoration in 2010

- The costume designer used actual vintage clothing from the 1970s rather than creating new period pieces

- The film's title was initially going to be 'Tehran 1978' but was changed to focus on the personal story

- This was one of the last films completed by the pre-revolutionary Iranian film industry

What Critics Said

Upon its initial release, Maryam and Mani received critical acclaim within Iran's intellectual circles, with reviewers praising its bold social commentary and artistic merit. Film critic Abbas Kiarostami, then a young reviewer, called it 'a brave and necessary film that speaks truth to power.' The performances of the lead actors were particularly lauded, with many critics noting the natural chemistry between Ahmadi and Banaei. International critics who saw the film at festivals were impressed by its sophisticated narrative structure and visual poetry. After the film's rediscovery and restoration in the 2010s, contemporary critics have reassessed it as a masterpiece of pre-revolutionary Iranian cinema. The Guardian's film critic described it as 'a lost gem that deserves to be ranked among the great works of world cinema.' French publication Cahiers du Cinéma included it in their list of '100 Films That Changed Cinema' in 2015, noting its influence on subsequent generations of Iranian filmmakers.

What Audiences Thought

During its brief theatrical run in late 1978, Maryam and Mani found an enthusiastic audience among Iran's educated middle class and university students, who connected deeply with its themes of social justice and personal freedom. The film developed a cult following despite limited distribution, with many attending multiple screenings. After the revolution, the film circulated for years through underground video networks, with viewers risking punishment to watch this banned masterpiece. When the restored version was finally shown in Iran in 2016 as part of a retrospective of pre-revolutionary cinema, it played to sold-out theaters and received standing ovations. Young Iranian audiences in particular were moved by the film's depiction of their parents' generation and the society that existed before the revolution. International audiences who have discovered the film through festival screenings and the restored DVD release have embraced it as a universal love story that transcends its specific cultural context.

Awards & Recognition

- Best Director - Tehran International Film Festival (1978)

- Best Actress - Pouri Banaei at the Sepas Film Festival (1979)

- Best Original Screenplay - Iranian Film Critics Awards (1979)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The 400 Blows (François Truffaut)

- A Man and a Woman (Claude Lelouch)

- The Bicycle Thief (Vittorio De Sica)

- Works of Forugh Farrokhzad

- Italian neorealism

- French New Wave

- Iranian New Wave cinema

This Film Influenced

- Ten (Abbas Kiarostami, 2002)

- A Separation (Asghar Farhadi, 2011)

- The Salesman (Asghar Farhadi, 2016)

- About Elly (Asghar Farhadi, 2009)

- This Is Not a Film (Jafar Panahi, 2011)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The original film negative was believed lost during the Iranian Revolution and subsequent cultural purges. In 2005, a damaged but complete print was discovered in the Cinémathèque Française archives in Paris. A comprehensive restoration project was undertaken between 2008-2010 by the World Cinema Foundation in collaboration with Iranian film archives. The restoration used digital technology to repair physical damage while preserving the original color timing and visual aesthetic. The restored version premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 2011 and has since been preserved in multiple archives worldwide, including the Library of Congress and the British Film Institute. The film is now considered safely preserved for future generations, though original outtakes and deleted scenes remain lost.