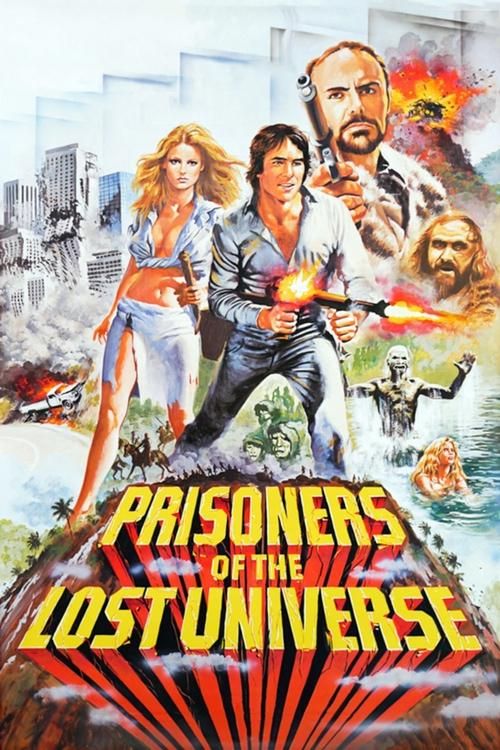

Prisoners of the Lost Universe

"Trapped in a world beyond time... fighting for survival with weapons from the past and knowledge from the future!"

Plot

When a scientific experiment involving a matter transporter goes awry, three individuals from modern Earth—scientist Dan, journalist Carrie, and warlord Kleel—are accidentally transported to a parallel universe that resembles a medieval fantasy world. In this strange dimension, they discover that while the inhabitants live with primitive technology and weaponry, the laws of physics from their own world still apply, allowing them to use their modern knowledge to create advanced weapons using medieval materials. The trio must unite the oppressed villagers to overthrow the tyrannical warlord who rules this dimension through fear and military might. As they adapt to their new environment, they face numerous challenges including hostile creatures, political intrigue, and the moral dilemma of introducing modern warfare concepts to a primitive society. The climactic battle sees them combining 20th-century tactical knowledge with medieval arms to liberate the populace and find a way back to their own dimension.

About the Production

The film was shot on a modest budget in just six weeks, utilizing many of the same sets and props from other fantasy productions of the era. The parallel universe sequences were filmed on soundstages with extensive matte paintings to create the otherworldly atmosphere. The production faced challenges with the limited special effects budget, forcing creative solutions for the matter transporter sequences and other sci-fi elements. Director Terry Marcel, known for his work on 'Hawk the Slayer', brought his experience with low-budget fantasy filmmaking to this project.

Historical Background

Released in 1983, 'Prisoners of the Lost Universe' emerged during a peak period for science fiction and fantasy cinema in the early 1980s. This era saw an explosion of genre films following the massive success of 'Star Wars' (1977) and the rise of home video creating new markets for lower-budget productions. The film reflected the cultural fascination with parallel universes and alternate realities, themes that were popular in both literature and cinema during this period. The early 80s also saw the rise of muscle-bound fantasy heroes like Conan, influencing the film's inclusion of a warrior character. Additionally, the Cold War anxieties of the time found expression in many films dealing with alternate realities and what might happen if our world were suddenly changed beyond recognition.

Why This Film Matters

While not a major commercial success, 'Prisoners of the Lost Universe' occupies a interesting place in cinema history as an early example of the 'modern person in fantasy world' subgenre that would later become more popular in films like 'Army of Darkness' and TV shows like 'Stargate'. The film's premise of combining modern knowledge with medieval technology anticipated themes that would become common in later science fiction and fantasy works. It represents a transitional period in genre filmmaking, sitting between the practical effects-driven fantasy of the late 70s and the more sophisticated productions that would emerge later in the decade. The film has gained a modest cult following among fans of 1980s B-movies and is often discussed in retrospectives about Richard Hatch's post-'Battlestar Galactica' career.

Making Of

The production of 'Prisoners of the Lost Universe' was a typical example of early 1980s low-budget genre filmmaking. Director Terry Marcel, coming off the cult success of 'Hawk the Slayer', conceived the project as a way to capitalize on the growing popularity of science fiction and fantasy films following the success of 'Star Wars' and 'Conan the Barbarian'. The casting of Richard Hatch was a strategic move to attract his 'Battlestar Galactica' fanbase. The film faced numerous production challenges, including budget constraints that forced the crew to reuse props and sets from other productions. The matter transporter sequences proved particularly difficult to execute convincingly with limited resources, leading to creative solutions involving multiple exposure techniques and practical effects. Despite these challenges, the cast and crew maintained a positive attitude, with Richard Hatch later commenting that the experience was like 'making a movie with friends in your backyard, but with professional equipment'.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Alan Hume, who also worked on 'For Your Eyes Only' and 'Return of the Jedi', attempted to create a distinctive visual style that would differentiate the parallel universe from modern Earth. The Earth sequences were shot with a more conventional, realistic approach, while the alternate dimension scenes employed warmer color palettes and more dramatic lighting to establish the fantasy setting. The film makes extensive use of matte paintings to expand the scope of the world beyond what could be practically built on the budget. The action sequences, though limited by budget, feature dynamic camera movement and editing that attempts to create excitement despite the constraints. The matter transporter effects, while dated by modern standards, were innovative for their time, using multiple exposure techniques and practical lighting effects.

Innovations

While 'Prisoners of the Lost Universe' was not a groundbreaking film in terms of technical innovation, it did feature some creative solutions to the challenges of low-budget genre filmmaking. The matter transporter sequences, though simple by modern standards, used a combination of practical effects including smoke machines, colored gels, and early video feedback techniques to create the illusion of dimensional travel. The production team developed a cost-effective method for creating the parallel universe's distinctive look using color filters during filming rather than relying entirely on post-production processes. The film also featured some early attempts at combining practical makeup effects with optical processing for the creature designs. These techniques, while rudimentary compared to big-budget productions of the era, demonstrated ingenuity in maximizing visual impact within severe budget constraints.

Music

The musical score was composed by Michael J. Lewis, who brought his experience from other fantasy and science fiction productions to create a soundtrack that blended orchestral grandeur with electronic elements. The main theme features a heroic brass melody that captures the adventure aspect of the story, while the parallel universe sequences incorporate more mysterious and exotic instrumentation. The score makes effective use of synthesizers alongside traditional orchestra to create the sense of otherworldliness. While the soundtrack was never officially released as an album, portions of it have circulated among film music enthusiasts. The music successfully elevates many scenes beyond what the visuals alone could achieve, particularly in the action sequences where the driving percussion and brass sections create tension and excitement.

Famous Quotes

In this world, our knowledge is their magic—and their weapons are our only hope for survival.

We may be prisoners of this universe, but we won't be prisoners of fear!

Modern science meets medieval warfare—let's see who wins.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening matter transporter accident where the three protagonists are violently thrown between dimensions, featuring swirling colors and disorienting visual effects that establish the film's sci-fi premise.

- The climactic battle sequence where the heroes combine 20th-century tactical knowledge with medieval weaponry, using formations and strategies completely alien to the fantasy world's inhabitants.

Did You Know?

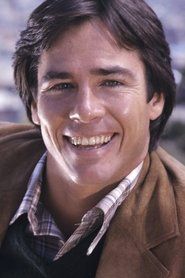

- Richard Hatch, who plays Dan, was best known at the time for his role as Captain Apollo in the original 'Battlestar Galactica' series

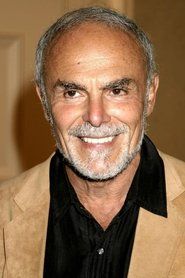

- John Saxon's character Kleel was originally written as a much smaller role but was expanded after Saxon signed on to the project

- The film's working title was 'Dimension Warriors' before being changed to 'Prisoners of the Lost Universe'

- Many of the medieval weapons used in the film were authentic replicas borrowed from a private collector

- The matter transporter effect was achieved using a combination of practical effects including smoke, mirrors, and early video feedback techniques

- Kay Lenz performed her own stunts in several action sequences, including a fall from a 15-foot platform

- The film was one of the first to explore the 'tech in medieval setting' trope that would later become popular in films and TV shows

- Despite being a British production, the film was financed primarily with American money and aimed at the US market

- The parallel universe scenes were filmed using a special color filter technique to give them a distinctive otherworldly appearance

- The film's score was composed by Michael J. Lewis, who also worked on 'The Medusa Touch' and 'The People That Time Forgot'

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception for 'Prisoners of the Lost Universe' was generally mixed to negative. Critics praised the ambitious premise but criticized the execution, particularly the limited special effects and sometimes awkward pacing. The Los Angeles Times noted that the film 'struggles to balance its science fiction and fantasy elements' while Variety called it 'a modest genre effort that doesn't quite achieve its potential'. Modern reassessments have been somewhat kinder, with some retro film critics appreciating it as a product of its time and noting its place in the evolution of the sci-fi/fantasy hybrid genre. The performances, particularly John Saxon's turn as the villain, have received some praise for elevating the material beyond its B-movie roots.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception in 1983 was modest, with the film performing poorly in its limited theatrical run. However, it found more success on the emerging home video market, where its blend of action and sci-fi elements appealed to genre fans looking for weekend entertainment. In the years since, it has developed a small but dedicated cult following among enthusiasts of 1980s genre cinema. Online forums and retro movie communities often discuss it fondly as an example of earnest, if flawed, 80s filmmaking. Many viewers appreciate the film's earnest attempt at creating an imaginative world despite its obvious budget limitations, with some considering it a 'guilty pleasure' worth revisiting.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Star Wars

- The Time Machine

- Conan the Barbarian

- Battlestar Galactica

- Flash Gordon

This Film Influenced

- Army of Darkness

- Stargate

- Timeline

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film exists in complete form and has been preserved through various home video releases. While no official restoration has been undertaken, the film survives on VHS, DVD, and various digital platforms. The original film elements are believed to be stored in archives, though they have not undergone extensive preservation work. Several bootleg versions circulate among collectors, some of which offer better quality than official releases.