Robinson Crusoe

Plot

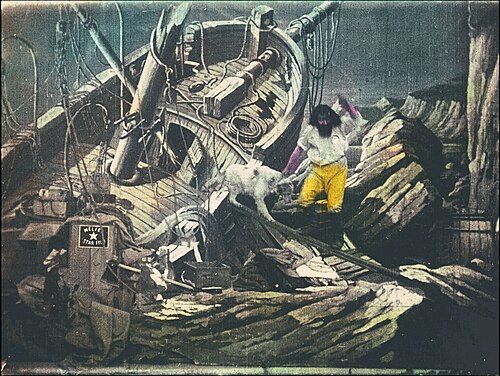

Georges Méliès' adaptation follows the classic tale of Robinson Crusoe, a shipwrecked sailor who finds himself stranded on a deserted island. After his vessel is destroyed in a violent storm, Crusoe washes ashore and must learn to survive using his wits and resources from the wreck. He builds a shelter, finds food, and eventually encounters Friday, a native whom he rescues from cannibals and educates. The film showcases Crusoe's years of isolation, his ingenious adaptations to island life, and his eventual rescue when a passing ship spots his signal fire. Méliès brings his signature magical touches to this survival story, incorporating theatrical special effects and elaborate stagecraft to depict the passage of time and Crusoe's various adventures on the island.

Director

Cast

About the Production

Filmed in Méliès's glass-walled studio in Montreuil, which allowed natural lighting for the extensive hand-coloring process. The film required elaborate sets including a ship, island beach, and Crusoe's dwelling. Méliès employed his trademark substitution splices and multiple exposure techniques to create magical effects. The hand-coloring was done by a team of women workers in Méliès's color workshop, with each frame individually painted using stencils. The production took several weeks, an unusually long time for films of this era.

Historical Background

1902 was a pivotal year in early cinema, occurring just seven years after the Lumière brothers' first public screening. Georges Méliès was already established as cinema's first great visual artist and special effects pioneer. This was the same year Méliès created his most famous work, 'A Trip to the Moon' (Le Voyage dans la Lune). The film industry was transitioning from simple actualities and trick films to more complex narrative features. 'Robinson Crusoe' represented an early attempt at adapting a well-known literary work to the new medium of cinema. The hand-coloring technique was particularly significant, as color film technology would not be invented for another decade. The film emerged during the Belle Époque in France, a period of artistic innovation and cultural confidence that Méliès's work exemplified.

Why This Film Matters

'Robinson Crusoe' holds immense cultural significance as one of the earliest feature-length narrative films and the first adaptation of one of English literature's most enduring works. It demonstrated that cinema could handle complex, extended narratives rather than just brief sketches or actualities. The film's hand-coloring showed that cinema could be a visually rich artistic medium, not just a mechanical reproduction of reality. Méliès's adaptation helped establish the practice of literary adaptation in cinema, a tradition that would become central to the film industry. The film also represents an early example of international cinema, as Robinson Crusoe was already a globally recognized story. Its restoration and preservation have made it an important document of early cinematic techniques and storytelling approaches, providing modern scholars and audiences with insight into how pioneers like Méliès envisioned the possibilities of the new medium.

Making Of

The production of 'Robinson Crusoe' represented one of Méliès's most ambitious undertakings of 1902. The elaborate ship set was built on an articulated platform that could be tilted and shaken to simulate the storm and wreck. For the hand-coloring process, Méliès employed a team of skilled female colorists who worked in his workshop, using a stencil method to apply colors to each individual frame. The island scenes were created using painted backdrops and real sand, props, and vegetation. Méliès used his famous substitution splices technique to make characters and objects appear and disappear magically, particularly in the sequences showing Crusoe's survival and his meeting with Friday. The film required extensive planning and multiple takes, as any error in the hand-coloring process could not be corrected. André Deed's performance as Friday included physical comedy elements that would later become his trademark as a silent film star.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'Robinson Crusoe' reflects Méliès's theatrical background, featuring static camera positions typical of early cinema but with elaborately designed sets that create depth and visual interest. The film employs Méliès's signature techniques of substitution splices, multiple exposures, and dissolves to create magical effects. The hand-coloring adds a rich visual dimension, with careful attention to color coding for different elements of the composition. The shipwreck sequence uses innovative camera angles and effects to convey the violence of the storm. The island scenes utilize painted backdrops combined with real props to create a convincing tropical environment. The color work is particularly sophisticated for its time, with flesh tones, natural colors for vegetation, and dramatic colors for special effects sequences.

Innovations

'Robinson Crusoe' showcases several important technical achievements for 1902. The hand-coloring process represents one of the most elaborate examples of this technique from the early cinema period. The film's use of multiple exposure and substitution splices to create complex narrative effects was advanced for its time. The construction of elaborate sets, including a functional ship set that could be manipulated to simulate a wreck, demonstrated sophisticated production design. The film's length of 15 minutes was unusually ambitious for 1902, requiring more complex narrative structure and editing than typical films of the era. The restoration of surviving footage has also contributed to technical knowledge about early film preservation and color restoration techniques.

Music

As a silent film, 'Robinson Crusoe' would have been accompanied by live music during its original exhibition. The typical accompaniment would have been a pianist or small ensemble performing popular songs, classical pieces, or improvised music appropriate to the action on screen. Méliès's films often had suggested musical pieces listed in their exhibition catalogs. Modern screenings of the restored version typically feature newly composed scores or period-appropriate music. The hand-colored version of the film suggests that Méliès envisioned a rich sensory experience, implying that musical accompaniment would have been carefully chosen to enhance the visual spectacle.

Memorable Scenes

- The spectacular shipwreck sequence using multiple effects and miniature work

- Robinson Crusoe's first appearance on the deserted island surveying his surroundings

- The rescue of Friday from the cannibals with dramatic action and effects

- The construction of Crusoe's shelter and domestic arrangements on the island

- The final rescue sequence with the signal fire and approaching ship

Did You Know?

- This was the first-ever film adaptation of Daniel Defoe's 1719 novel 'Robinson Crusoe'

- The film was hand-colored frame by frame, a painstaking process that Méliès pioneered for his more elaborate productions

- André Deed, who played Friday, would later become a famous comedy star in his own right, creating the character 'Cretinetti'

- The film was originally released as part of Méliès's Star Film catalog as number 397-398

- Méliès himself played Robinson Crusoe, continuing his practice of starring in his own major productions

- The surviving 12.5 minutes were discovered in a film archive and restored in the 1990s

- The shipwreck sequence used one of Méliès's most complex special effects combinations, involving miniature work, smoke effects, and multiple exposures

- At 15 minutes, it was considered an exceptionally long film for its time, when most films were under 3 minutes

- The film was distributed internationally, with English-language titles added for American and British markets

- Méliès's version significantly simplified the novel, focusing on the visual spectacle rather than the philosophical themes of the original work

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of 'Robinson Crusoe' is difficult to document due to the limited film journalism of 1902. However, Méliès's films were generally well-received by the trade press and public. The film was noted in film catalogs as one of Méliès's more elaborate productions. Modern critics and film historians regard 'Robinson Crusoe' as an important example of early narrative cinema and Méliès's sophisticated approach to adapting literary works. The surviving colored version has been praised for its visual beauty and technical achievement, with particular appreciation for the hand-coloring work. Film scholars often cite it as evidence of Méliès's ambition to elevate cinema from mere novelty to art form. The restoration has allowed contemporary critics to assess the film's place in cinema history more accurately, recognizing it as a significant step toward the feature-length narrative films that would dominate cinema in subsequent decades.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception in 1902 would have been enthusiastic, as Méliès was one of the most popular filmmakers of his time. The film's length and spectacle would have made it a special attraction in fairgrounds and early cinemas. The hand-colored version would have commanded higher admission prices due to the expensive coloring process. Modern audiences who have seen the restored version typically express fascination with the film's visual beauty and historical significance. The film is frequently shown at film festivals and special screenings of early cinema, where it receives appreciative responses from viewers interested in film history. The combination of adventure story, exotic locations, and Méliès's magical effects would have appealed to turn-of-the-century audiences seeking entertainment and wonder.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Robinson Crusoe novel by Daniel Defoe (1719)

- Stage adaptations of Robinson Crusoe

- Contemporary adventure literature

- Méliès's earlier theatrical work

- Paintings of exotic locations and shipwrecks

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent Robinson Crusoe adaptations

- Adventure films of the silent era

- Feature-length narrative films

- Literary adaptations in cinema

- Hand-colored films of the 1900s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Partially preserved - approximately 12.5 minutes of the original 15-minute hand-colored version have been found and restored. The film exists in the archives of several institutions including the Cinémathèque Française. The restored version represents one of the best-preserved examples of Méliès's hand-colored work from this period. The restoration work was conducted in the 1990s using the best available surviving elements. Some footage may still be lost, as was common with films from this era.