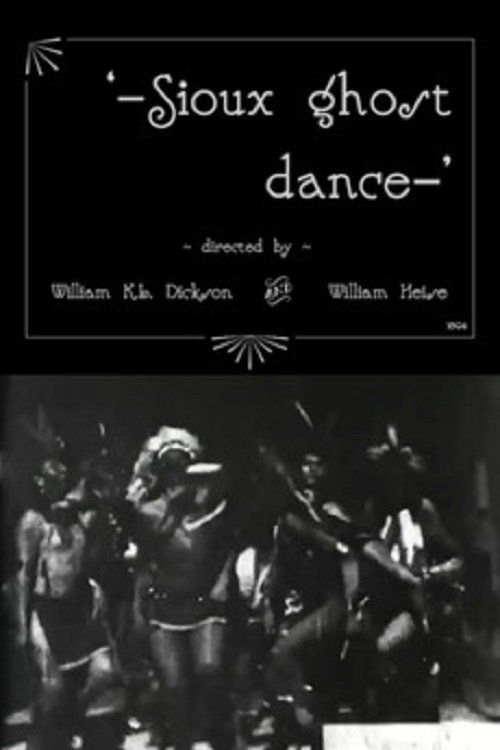

Sioux Ghost Dance

Plot

This short documentary film captures a group of Sioux Native American performers performing a traditional Ghost Dance ritual. The dancers are shown in full ceremonial attire, including war paint and traditional costumes, moving in synchronized patterns characteristic of the Ghost Dance ceremony. Filmed in a single continuous shot, the performers demonstrate the spiritual movements that were central to this religious movement that spread among Native American tribes in the late 1880s. The film serves as an ethnographic record of this significant cultural practice, which was believed to help restore Native American lands and bring back deceased ancestors. The entire performance is captured in the distinctive style of early cinema, with the dancers moving against the simple backdrop of Edison's Black Maria studio.

Director

About the Production

Filmed on September 24, 1894, at Edison's Black Maria studio using the Kinetograph camera. The performers were members of Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show who were brought to the studio specifically for this filming. The Black Maria, Edison's first film studio, was designed with a retractable roof to allow natural sunlight to illuminate the subjects, as electric lighting was not yet sufficient for film exposure. The camera was hand-cranked, and the entire film was shot in one continuous take, typical of early Edison productions.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a pivotal moment in American history and technological development. The 1890s marked the birth of commercial cinema, with Thomas Edison and William K.L. Dickson pioneering the Kinetoscope and Kinetograph systems. Simultaneously, this period represented the end of the American Indian Wars and the forced assimilation of Native American peoples onto reservations. The Ghost Dance movement itself had emerged in 1889 as a response to decades of oppression, broken treaties, and cultural destruction. The movement's association with the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890, where over 200 Lakota were killed by U.S. troops, made it a sensitive and controversial subject. The film also coincided with the peak popularity of Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, which both romanticized and commodified Native American culture for mainstream American audiences. This short documentary therefore exists at the intersection of technological innovation, cultural documentation, and the complex relationship between Native Americans and mainstream American society during the late 19th century.

Why This Film Matters

This film holds immense cultural significance as the earliest moving image documentation of Native American culture and the first appearance of Indigenous peoples in cinema. It represents a crucial moment in the history of ethnographic film, capturing a traditional ceremony that was rapidly disappearing due to forced assimilation policies. The film also marks the beginning of Native American representation in motion pictures, a legacy that would evolve dramatically over the following century. While the authenticity of the performance has been debated by historians, it nonetheless provides invaluable visual documentation of late 19th-century Native American ceremonial dress and dance movements. The film's existence demonstrates how early cinema was immediately drawn to documenting 'exotic' or 'vanishing' cultures, a trend that would continue throughout the silent era. For contemporary viewers, the film serves as a powerful reminder of the resilience of Native American culture and the complex history of its representation in American media.

Making Of

The production of 'Sioux Ghost Dance' took place during the early days of commercial filmmaking at Edison's revolutionary Black Maria studio. William K.L. Dickson, Edison's primary assistant in developing motion picture technology, personally operated the Kinetograph camera. The Native American performers were recruited from Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, which was extremely popular at the time and employed numerous Native American actors. The studio had to be rotated on a circular track to follow the sun's movement across the sky, ensuring consistent lighting throughout the filming day. The performers wore authentic ceremonial costumes brought specifically for the filming, though historians note that the dance was likely adapted for the camera and may not have been a completely authentic representation of the Ghost Dance ceremony. The entire filming process would have been extremely challenging for the performers, who had to maintain their positions and movements under the hot studio lights and while being filmed by the noisy, bulky Kinetograph camera.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Sioux Ghost Dance' represents the state of the art in 1894 motion picture technology. Shot using Edison's Kinetograph camera, the film was captured on 35mm film using a continuous feed mechanism that Dickson had developed. The camera was hand-cranked, typically running at approximately 16 frames per second, though the exact speed could vary based on the operator. The entire film consists of a single static wide shot, with the camera positioned to capture the full group of dancers. The lighting was natural sunlight, directed into the Black Maria studio through its retractable roof and white-painted interior walls. The composition follows the conventions of early Edison films, with subjects positioned centrally in the frame to maximize visibility for Kinetoscope viewers. The visual style is characterized by its stark simplicity and the high contrast typical of early film emulsions. While technically primitive by modern standards, the cinematography successfully preserves the movements and costumes of the performers with remarkable clarity for the period.

Innovations

The film represents several significant technical achievements in early cinema history. It was produced using Edison's Kinetograph, one of the first practical motion picture cameras, which employed an intermittent mechanism to advance the film frame by frame. The Black Maria studio itself was an innovation, designed specifically for film production with its rotating base and retractable roof system to optimize natural lighting conditions. The film showcases the early use of 35mm film, which would become the industry standard for the next century. The synchronization of multiple performers in a single continuous take demonstrated the growing sophistication of early film production techniques. The preservation of the film through the Library of Congress's paper print collection also represents an important archival achievement, as early films were often lost due to the unstable nature of nitrate film stock. The film's existence today is a testament to both the durability of early motion picture technology and the importance of systematic film preservation efforts.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening shot reveals a group of Native American performers standing in formation, their bodies adorned in elaborate traditional costumes and distinctive war paint patterns. As the dance begins, the performers move in synchronized patterns, their bodies swaying and stepping in rhythm while maintaining the ceremonial poses characteristic of the Ghost Dance ritual. The camera captures the full spectacle of their movements, with feathers and traditional accessories creating dynamic visual patterns as they dance. The scene culminates with the performers completing the ceremonial sequence, their bodies frozen in final poses that showcase the intricate details of their ceremonial attire against the simple backdrop of Edison's studio.

Did You Know?

- This film represents the first appearance of Native Americans in motion picture history

- The Ghost Dance was a religious movement that emerged in 1889 and was believed to restore Native American lands and ways of life

- The film was shot on the same day as 'Buffalo Dance,' another Edison short featuring Native American performers

- The performers were not actually Sioux but likely members of various tribes employed by Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show

- The original film was 40 feet long, which at Edison's standard 16 frames per foot would run approximately 16 seconds at 16 fps

- The film was part of Edison's 'Indian Pictures' series, which included several shorts featuring Native American performers

- The Ghost Dance movement was associated with the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890, making this film historically significant

- Edison catalog listed the film at $7.50, a substantial price for the time

- The Black Maria studio was nicknamed the 'Doghouse' by Edison employees due to its appearance

- This film is preserved in the Library of Congress's paper print collection

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of 'Sioux Ghost Dance' is minimal, as film criticism as we know it did not exist in 1894. The film was primarily reviewed in trade publications and Edison's own marketing materials, which emphasized its educational and novelty value. The Edison Film Catalog described it as showing 'one of the most peculiar customs of the Sioux Tribe,' reflecting the ethnographic curiosity of the time. Modern film historians and critics recognize the film as a landmark documentary, though they often note the problematic aspects of its production context. Charles Musser, a prominent film historian, has written extensively about this film and its companion pieces, noting their importance in early cinema history while acknowledging the colonial gaze through which they were produced. The film is now studied as an example of early ethnographic cinema and as a document of the complex relationship between Native Americans and early American entertainment industries.

What Audiences Thought

Original audience reception of 'Sioux Ghost Dance' would have been experienced through individual Kinetoscope viewing machines rather than collective theater screenings. Viewers in 1894 would have been fascinated by the novelty of seeing moving images, particularly of subjects they might have only read about or seen in photographs. The film appealed to the Victorian-era fascination with 'exotic' cultures and the popular interest in Native American life fueled by Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show. Contemporary audiences viewing the film today often express a mix of fascination at seeing such early footage and critical awareness of the colonial context in which it was made. The film has become an important historical document for Native American communities, providing rare visual evidence of their ancestors' cultural practices. Modern viewers frequently comment on the poignancy of seeing these performers preserved in motion picture history, knowing the challenges their communities would face in the decades that followed.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Edison's earlier experimental films

- Eadweard Muybridge's motion studies

- Étienne-Jules Marey's chronophotography

- Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show performances

- 19th-century ethnographic photography

This Film Influenced

- Buffalo Dance (1894)

- Indian Day School (1898)

- A Trip to the Moon (1902) - in its depiction of 'exotic' cultures

- Nanook of the North (1922) - as ethnographic documentary

- The Silent Enemy (1930) - early Native American narrative film

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved and available for viewing. It was saved through the Library of Congress's paper print collection, a process where early films were printed on paper for copyright registration purposes. These paper prints have been digitally restored and transferred back to film format. The film is part of the National Film Registry's collection of historically significant American films. Multiple copies exist in various archives, including the Library of Congress, the Museum of Modern Art's film collection, and several university film archives. The preservation quality is remarkably good considering the film's age, with clear images and stable framing throughout the 16-second runtime.