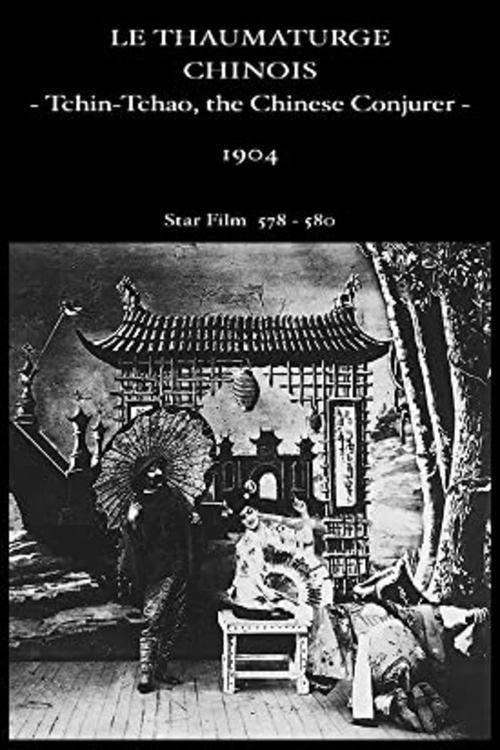

Tchin-Chao, the Chinese Conjurer

Plot

In this early Georges Méliès fantasy short, a Chinese conjurer dressed in elaborate traditional costume performs a series of magical transformations on a simple stage. The magician begins by duplicating his table, then transforms a fan into a parasol while making lanterns appear and disappear from thin air. In the film's most memorable sequence, the conjurer spins his parasol and produces a live dog, which then transforms into a woman before a masked man mysteriously appears. The performance culminates with the conjurer seating the woman and man on separate boxes, only to have them magically exchange positions multiple times, showcasing Méliès' mastery of substitution splices and stop-motion techniques.

Director

Cast

About the Production

Filmed in Méliès's glass studio in Montreuil, which allowed for optimal lighting control and the creation of his elaborate theatrical sets. The film showcases Méliès's signature substitution splice technique, where the camera would be stopped, objects or actors would be changed, and filming would resume to create magical transformations. The Chinese theme reflects the Western fascination with 'Oriental' exoticism that was popular in European entertainment at the turn of the century.

Historical Background

In 1904, cinema was still in its infancy, with films typically lasting only a minute or two and shown as part of variety programs in theaters and music halls. Georges Méliès was one of the few filmmakers treating cinema as an art form rather than just a novelty. This period saw the height of Méliès's creative output, as he produced hundreds of short films featuring magical transformations and fantastical scenarios. The film reflects the era's fascination with exoticism and colonial expansion, with Western audiences eager for glimpses of 'mysterious' Eastern cultures. Méliès's work represented a crucial bridge between stage magic and cinematic special effects, helping establish many techniques that would become fundamental to filmmaking.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents an important example of early cinematic special effects and the development of the fantasy genre in film. Méliès's substitution splice technique, showcased prominently in this work, would become a foundational special effect used throughout cinema history. The film also demonstrates how early cinema adapted theatrical magic traditions for the new medium, helping establish cinema as a vehicle for fantasy and wonder rather than just documentary recording. While the stereotypical portrayal of Chinese characters reflects the colonial attitudes of the era, the film remains significant for its technical innovations and its role in establishing the grammar of cinematic magic. Méliès's work, including this film, influenced countless filmmakers and helped establish cinema as a medium capable of creating impossible visions.

Making Of

Georges Méliès, a former magician and theater owner, applied his stage magic expertise to the new medium of cinema. The film was created using his signature substitution splice technique, which he discovered accidentally when his camera jammed and restarted, creating an apparent magical transformation. For this film, Méliès would have had to carefully choreograph each transformation, stopping the camera multiple times to change props, costumes, and actor positions. The dog transformation would have required precise timing to achieve the seamless effect of the animal becoming a woman. Méliès's glass studio allowed him to control lighting perfectly, essential for the multiple exposures and splices required. The film was likely shot in one day with Méliès performing all the magical actions himself, as was his custom for these short trick films.

Visual Style

The cinematography follows Méliès's typical theatrical style, with a fixed camera position capturing the entire stage as if viewing a theater performance. The lighting is bright and even, characteristic of his glass studio setup, which allowed for consistent exposure across the multiple takes needed for special effects. The camera work is static and straightforward, focusing attention on the magical transformations rather than camera movement. The visual composition is carefully staged to ensure clear visibility of each magical effect, with the conjurer positioned centrally and props arranged for maximum dramatic impact.

Innovations

The film showcases Méliès's pioneering use of substitution splices, where the camera is stopped and restarted to create the appearance of magical transformations. The multiple object transformations (table duplication, fan to parasol, dog to woman) demonstrate sophisticated understanding of editing for magical effect. The rapid succession of different transformations within a single minute-long film shows Méliès's ability to pack maximum spectacle into minimal runtime. The film also demonstrates early use of what would become known as 'stop-motion' techniques, where objects and actors are moved between takes to create impossible movements.

Music

As a silent film from 1904, it would have been accompanied by live music during exhibition, typically piano or organ music. The musical accompaniment would have been improvised by the theater musician, often using popular tunes of the era or appropriate 'Oriental' themed music to match the film's exotic setting. Méliès's films were sometimes accompanied by sound effects created by the theater's staff or mechanical devices, though no synchronized soundtrack was possible with the technology of the time.

Memorable Scenes

- The sequence where the conjurer spins his parasol and produces a live dog, which then magically transforms into a woman, represents one of Méliès's most complex multi-stage transformations and showcases his mastery of substitution splicing techniques.

Did You Know?

- This film is cataloged as Star Film #593-594 in Méliès's production catalog

- The Chinese character portrayed by Méliès reflects the period's theatrical conventions rather than authentic Chinese representation

- The dog transformation sequence was achieved using multiple substitution splices in rapid succession

- Méliès often played the lead roles in his own films, believing he could best execute the precise timing required for his special effects

- The film was hand-colored in some releases, a common practice for Méliès's more elaborate productions

- Like many Méliès films, it was designed to be part of a magic lantern show or theatrical program rather than standalone entertainment

- The simple backdrop was typical of Méliès's early films, focusing attention on the magical effects rather than elaborate scenery

- The film's title reflects the phonetic spelling common in early 20th century France for foreign names

What Critics Said

Contemporary reception of Méliès's films was generally positive, with audiences marveling at the seemingly impossible magical transformations. Critics and trade publications of the era noted the cleverness of Méliès's effects and his ability to create wonder within the short format. Modern film historians recognize this film as a representative example of Méliès's technical mastery and his contribution to the development of cinematic language. The film is often cited in scholarly works about early cinema and the origins of special effects, though it's considered less significant than Méliès's more famous works like 'A Trip to the Moon' (1902).

What Audiences Thought

Early 20th century audiences were reportedly delighted by Méliès's magical films, which provided a sense of wonder and impossibility that no other medium could offer at the time. The quick transformations and surprising appearances in films like this one were particularly popular, as they maximized the magical impact within the very short runtime. The exotic Chinese theme would have added to the novelty for European viewers, who had limited exposure to Chinese culture. These films were often shown repeatedly in the same program due to audience demand, with viewers trying to figure out how the effects were achieved.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage magic and illusion shows

- Theatrical conjuring performances

- Victorian era fascination with the exotic

- Music hall and variety show traditions

This Film Influenced

- Later Méliès trick films

- Early special effects films by other pioneers

- Modern magic-themed cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in archives and is part of the preserved Méliès collection. Multiple copies exist, including some with hand-coloring. It has been restored and digitized by various film archives including the Cinémathèque Française and is available through several classic film collections.