The Black Imp

Plot

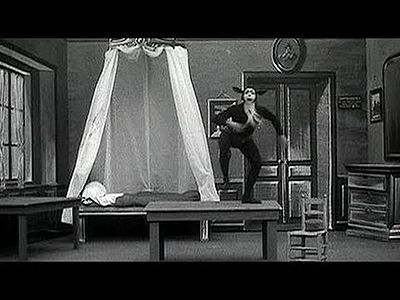

In this early fantasy comedy, a weary traveler arrives at an inn and checks into a room for the night. As he attempts to settle in and sleep, a mischievous black devil (imp) appears and begins to torment him through a series of magical pranks and transformations. The imp uses his supernatural powers to make furniture disappear and reappear, change size, and move about the room, driving the traveler to increasing frustration and desperation. The film culminates in a chaotic finale where the imp multiplies himself and creates utter pandemonium before finally disappearing, leaving the exhausted traveler to wonder if it was all a dream. The entire narrative showcases Méliès' mastery of cinematic magic and his penchant for theatrical, visually-driven storytelling.

Director

Cast

About the Production

Filmed in Méliès's glass-walled studio in Montreuil-sous-Bois, which allowed for natural lighting. The production used elaborate painted backdrops and theatrical props. Méliès employed multiple exposure techniques and substitution splices to create the magical effects. The devil costume was likely created in Méliès's own workshop, as he designed and built many of his own props and costumes.

Historical Background

1905 was a pivotal year in early cinema, occurring during the transition from short novelty films to more complex narrative storytelling. The film industry was still in its infancy, with most films being less than five minutes long and shown as part of variety programs. Méliès was one of the few filmmakers creating fantasy and narrative content, as most contemporaries focused on actualities and documentaries. This period also saw the rise of competing film companies and the beginning of international film distribution. The year 1905 came just before the film industry would shift its center from Europe to America, making Méliès's work particularly significant as representing the peak of European cinematic innovation.

Why This Film Matters

'The Black Imp' represents the maturation of Méliès's cinematic language and his contribution to establishing fantasy as a viable film genre. The film's use of supernatural themes and magical transformations influenced countless future filmmakers, from German Expressionists to modern fantasy directors. Méliès's work, including this film, helped establish cinema as a medium for imagination rather than just reality recording. The devil character became an archetype in horror and fantasy cinema, with Méliès's portrayal setting visual standards that would persist for decades. The film also demonstrates early cinema's theatrical roots, showing how stage magic traditions were translated to the new medium of film.

Making Of

Georges Méliès, a former magician and theater owner, applied his stage magic expertise to cinema. For 'The Black Imp,' he used his signature substitution splice technique, where the camera would be stopped, objects or actors would be changed, and filming would resume. The multiplication effect was created through multiple exposure, filming the same scene multiple times with the actor in different positions. Méliès performed in heavy makeup and costumes, often playing multiple roles in the same film. His studio was essentially a theatrical space with a painted backdrop, allowing him complete control over the visual environment. The devil costume and makeup were elaborate for the time, requiring Méliès to sit for hours in the makeup chair.

Visual Style

The cinematography was typical of Méliès's style, featuring a static camera position reminiscent of a theater audience's perspective. This allowed the audience to focus on the magical transformations occurring within the frame. The film used painted backdrops and theatrical set design to create the inn room environment. Lighting was natural, coming through the glass walls of Méliès's studio. The camera work was straightforward but effective, ensuring that the special effects were clearly visible and impactful.

Innovations

The film showcases several of Méliès's pioneering techniques, including substitution splices for magical appearances and disappearances, multiple exposure for character multiplication, and careful matte work for composite effects. The seamless transitions between effects were particularly advanced for 1905. Méliès's use of these techniques to serve narrative rather than as mere novelties represented an important step in cinematic storytelling. The film also demonstrates sophisticated editing rhythm, with the timing of effects carefully choreographed for maximum impact.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Black Imp' had no synchronized soundtrack. In its original exhibition, it would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small orchestra playing appropriate mood music. The musical accompaniment would have been improvisational, with dramatic music for the supernatural elements and comedic tunes for the traveler's frustrations. Modern screenings often use period-appropriate classical music or specially composed scores.

Famous Quotes

(Silent film - no dialogue) The film communicates through visual storytelling and pantomime performance

Memorable Scenes

- The sequence where the imp multiplies himself into multiple identical devils, creating chaos throughout the room and demonstrating Méliès's mastery of multiple exposure techniques

Did You Know?

- The Black Imp was released by Star Film Company as catalog number 641-642

- Méliès played both the traveler and the devil character through the use of multiple exposure techniques

- The film is also known by its French title 'Le Diable Noir'

- This was one of over 500 films Méliès created during his career

- The devil character was a recurring figure in Méliès's work, appearing in numerous films including 'The Devil's Castle' (1896)

- The film features some of Méliès's most sophisticated substitution splices for its time

- Méliès's glass studio allowed him to control lighting conditions essential for his special effects techniques

- The film was hand-colored in some releases, a common practice for important Méliès productions

- The imp's ability to multiply himself was achieved through multiple exposure, a technique Méliès pioneered

- This film represents Méliès's transition from simple trick films to more complex narrative fantasies

What Critics Said

Contemporary reception of 'The Black Imp' is not well-documented, as film criticism was still in its infancy in 1905. However, Méliès's films were generally popular with audiences and respected for their technical innovation. Modern critics and film historians recognize 'The Black Imp' as a representative example of Méliès's mature style, praising its sophisticated use of special effects and theatrical presentation. The film is often cited in scholarly works about early cinema and the development of visual effects. Film historians consider it an important example of how narrative complexity was developing in cinema's first decade.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1905 reportedly enjoyed Méliès's fantasy films for their magical qualities and visual spectacle. 'The Black Imp' would have been particularly entertaining due to its rapid succession of tricks and the humorous situation of the tormented traveler. Méliès's films were popular across Europe and America, with his Star Film Company having international distribution. Modern audiences viewing the film at film festivals or in retrospectives typically appreciate it for its historical significance and charming, theatrical approach to storytelling.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage magic and theatrical traditions

- Gothic literature

- French theatrical comedy

- Méliès's background as a magician

- Popular devil folklore of the period

This Film Influenced

- Later horror-comedy films

- Fantasy films featuring magical mischief

- Surrealist cinema of the 1920s

- Modern films about supernatural troublemakers

- The special effects techniques influenced countless future filmmakers

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in various archives, including the Cinémathèque Française and the Museum of Modern Art. Some versions exist in black and white, while others show evidence of hand-coloring. The film has been restored and digitized as part of various Méliès retrospectives and is considered well-preserved for a film of its era.