The Burglar's Slide for Life

Plot

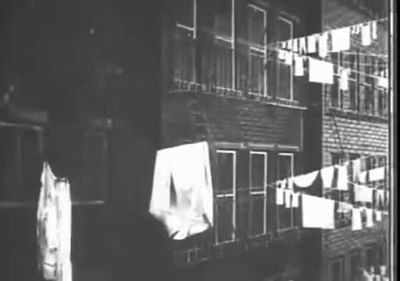

A cunning burglar breaks into an apartment building and begins systematically stealing valuables from various rooms. When discovered mid-theft, the thief desperately seeks an escape route and ingeniously decides to slide down the building's clothesline connecting apartments. The burglar successfully glides down the makeshift zipline, seemingly making a daring escape, but his freedom is short-lived as the family dog alerts the residents and ultimately leads to his capture. The film concludes with the burglar being apprehended, demonstrating that even the cleverest criminal plans can be foiled by unexpected circumstances.

Director

About the Production

Filmed during Edison's peak production period, this short comedy utilized practical effects and stunt work typical of Porter's innovative approach. The clothesline slide sequence required careful setup and timing, representing an early example of action-comedy in cinema. The production likely used Edison's own studio facilities with constructed sets to simulate the apartment building exterior.

Historical Background

This film was produced during a pivotal period in American cinema history, 1905, when the industry was transitioning from novelty exhibitions to narrative storytelling. The Edison Manufacturing Company, under Thomas Edison's leadership, was one of the dominant forces in early American film production, engaged in fierce competition with other studios like Biograph and Vitagraph. Urban America was experiencing rapid growth and modernization, with rising concerns about crime and security in cities, which made burglary themes particularly resonant with contemporary audiences. The film reflects the emerging genre of chase comedies that would become popular in the following years. This was also the year before the formation of the Motion Picture Patents Company, the trust that would attempt to control the American film industry.

Why This Film Matters

The Burglar's Slide for Life represents an important step in the development of American comedy cinema, demonstrating the evolution from simple trick films to narrative-driven entertainment. The film's use of physical comedy and stunt work presaged the slapstick traditions that would dominate American comedy in the following decade, particularly in the work of comedians like Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. The burglary theme reflected contemporary urban anxieties while providing a cathartic resolution where crime doesn't pay. The film also showcases early American cinema's growing sophistication in visual storytelling and its ability to create engaging narratives within the severe time constraints of early exhibition formats. Its preservation of the Edison style provides valuable insight into early 20th century American filmmaking practices and audience preferences.

Making Of

Edwin S. Porter, who had recently achieved fame with 'The Great Train Robbery' (1903), continued his exploration of crime-themed narratives with this short comedy. The production utilized Edison's indoor studio facilities with constructed exterior sets, a common practice to control lighting and weather conditions. The clothesline slide sequence required careful engineering to ensure the performer's safety while creating a convincing visual spectacle. The film was shot quickly, as was typical for Edison productions of this era, with minimal takes and straightforward camera setups. Porter's experience as a cameraman and projectionist informed his practical approach to filmmaking, focusing on clear visual storytelling that would play well to audiences of all backgrounds.

Visual Style

The film was photographed using Edison's own 35mm cameras with fixed positioning typical of the era. The cinematography employed static wide shots to capture the full action, particularly important for the clothesline slide sequence. The lighting was natural or studio-lit to ensure clear visibility of the action. The composition followed Porter's characteristic approach of staging action within the frame for maximum clarity and impact. The camera work was straightforward but effective, allowing audiences to clearly follow the narrative progression from burglary to escape to capture.

Innovations

The film's clothesline slide sequence represents an early example of stunt work in American cinema, requiring careful rigging and performer coordination. The production utilized Edison's improved film stock and camera equipment, benefiting from the company's continuous technical innovations. The film demonstrates Porter's growing mastery of narrative construction within the constraints of early cinema technology. The seamless integration of interior and exterior scenes (even when shot on studio sets) showed advancing techniques in continuity and spatial relationships in film.

Music

As a silent film, it would have been accompanied by live musical performance during exhibition. Typical accompaniment might have included piano or organ music, with popular tunes of the era or improvisation to match the on-screen action. Sound effects might have been provided by theater staff, particularly during the escape sequence. No specific musical score was composed for the film, as was standard practice for Edison productions of this period.

Memorable Scenes

- The climatic clothesline slide sequence where the burglar dramatically escapes down the line between buildings, only to be thwarted by the alert family dog - an early example of action-comedy spectacle in American cinema

Did You Know?

- This film was part of Edwin S. Porter's prolific 1905 output, during which he directed approximately 50 films for Edison

- The clothesline slide effect was achieved using a real performer sliding down a rigged line, one of the earliest examples of stunt work in American cinema

- The film was shot on 35mm film using Edison's own proprietary equipment and film stock

- Like many Edison films of this era, it was likely accompanied by live music or sound effects during exhibition

- The dog in the film represents one of the earliest uses of an animal character as a plot device in American cinema

- This film was distributed through Edison's network of exchanges and licensed exhibitors across the United States

- The original film was tinted by hand in some copies, a common practice for Edison productions to add visual appeal

- Porter often used burglary themes in his comedies, reflecting contemporary urban anxieties about crime in growing cities

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in trade publications like The New York Clipper and The Moving Picture World noted the film's entertaining qualities and clever use of the clothesline gimmick. Critics of the era praised Porter's ability to create engaging scenarios within the short format limitations. Modern film historians recognize the film as a representative example of Porter's work during his Edison period and an important artifact in the development of American comedy cinema. The film is often cited in scholarly works about early American film comedy and Porter's contributions to cinematic language.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by contemporary audiences who appreciated its blend of crime, comedy, and spectacle. The clothesline slide sequence was particularly popular with viewers, representing the kind of thrilling visual entertainment that early cinema audiences sought. The film's clear narrative and satisfying resolution where the criminal is caught aligned with the moral expectations of the time. Like many Edison productions of this era, it circulated widely through the company's distribution network and was a reliable attraction for vaudeville theaters and dedicated nickelodeons that were beginning to emerge in 1905.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Great Train Robbery (1903)

- European chase comedies

- Stage melodramas

- Vaudeville routines

This Film Influenced

- Later chase comedies

- Keystone comedies

- Slapstick films of the 1910s

- Burglar-themed comedies

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in archives, with copies held at the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art. Some versions exist as paper prints deposited for copyright purposes, which have been transferred back to film. The preservation status is considered good for a film of this era, though original camera negatives are likely lost.