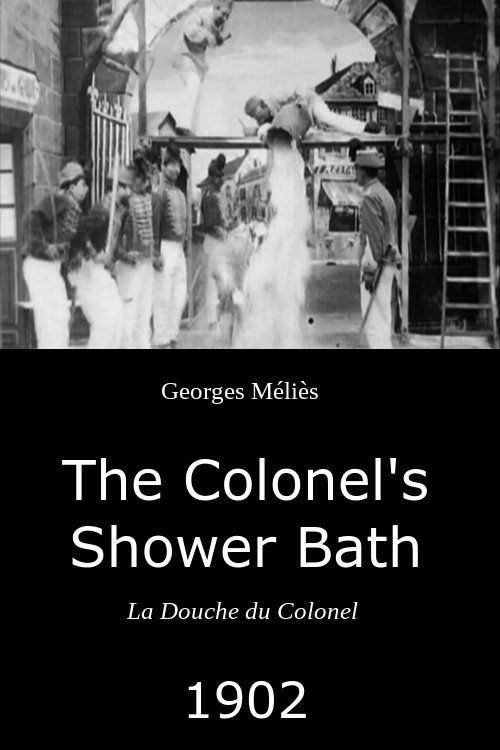

The Colonel's Shower Bath

Plot

In this early comedy short, a military colonel enters what appears to be a conventional shower bath facility, only to experience a series of increasingly absurd and magical transformations. As the colonel attempts to wash himself, the shower apparatus defies the laws of physics and logic, spraying water in impossible directions and causing the officer to undergo various comical metamorphoses. The situation escalates as the shower mechanism takes on a life of its own, ultimately reducing the dignified military man to a state of complete disarray and confusion. The film showcases Méliès' signature blend of theatrical comedy and visual trickery, using the simple premise of a shower to execute a series of magical gags that would have delighted and astonished audiences of the time.

Director

About the Production

Like most Méliès films of this period, it was shot in a single take with a stationary camera, using elaborate stage sets and mechanical props. The shower apparatus was a custom-built prop designed to create the various magical effects. The film was hand-colored frame by frame for special exhibition copies, a laborious process that Méliès employed for his premium releases.

Historical Background

The year 1902 was a pivotal moment in early cinema, representing the transition from simple actualities and trick films to more complex narrative storytelling. This was the same year Méliès released his masterpiece 'A Trip to the Moon,' which would become one of the most influential films of the early cinema era. The film was made during the height of the Boer War and growing tensions between European powers, making military-themed content particularly relevant to contemporary audiences. France was still recovering from the trauma of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, and military themes carried significant cultural resonance. The film also emerged during the early days of film piracy, with Méliès struggling to protect his works from unauthorized duplication, particularly by American producers like Thomas Edison and Siegmund Lubin. This period saw the establishment of the first dedicated movie theaters, moving film exhibition from fairgrounds and vaudeville houses to permanent venues, creating greater demand for short, entertaining films like Méliès' comedies.

Why This Film Matters

While not as famous as Méliès' fantasy epics, 'The Colonel's Shower Bath' represents an important example of early cinematic comedy and the development of visual gag structure. The film demonstrates how early filmmakers adapted theatrical comedy traditions to the new medium of cinema, using the unique possibilities of film to create impossible scenarios that could never be staged live. The military comedy genre would become a staple of cinema throughout the 20th century, and Méliès' early experiments helped establish the visual language of military humor. The film also showcases Méliès' role in developing the concept of the transformation scene, which would become fundamental to both comedy and fantasy filmmaking. Its preservation and study today provides valuable insight into the early development of cinematic comedy and the transition from stage magic to film special effects.

Making Of

The production of 'The Colonel's Shower Bath' exemplified Méliès' theatrical approach to filmmaking, treating the camera as a recording device for stage magic rather than a tool for cinematic storytelling. The film was shot on Méliès' custom-built glass studio stage in Montreuil, which allowed for elaborate lighting effects and the integration of theatrical machinery. The shower prop was a complex mechanical device that Méliès and his workshop constructed specifically for this film, featuring hidden pipes, pumps, and reservoirs to create the various impossible water effects. The substitution splices that create the magical transformations were accomplished by stopping the camera, making changes to the scene or actors, and then resuming filming - a technique Méliès pioneered. The hand-coloring process, when used, was performed by a team of women workers in Méliès' studio who applied color to each individual frame using fine brushes, making the colored versions extremely valuable and rare.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'The Colonel's Shower Bath' follows Méliès' characteristic style of the period: a single, static camera position capturing the entire scene as if filmed from a theater seat. This approach reflects Méliès' background as a stage magician and his conception of cinema as 'theater with a new dimension.' The lighting was theatrical in nature, using footlights and overhead illumination to create dramatic effects and highlight the magical transformations. The camera work was straightforward but precise, as the timing of substitution splices required exact coordination between the camera operator and the performers. When viewed in hand-colored versions, the film would have featured the vibrant, artificial colors that were characteristic of Méliès' premium productions, with each frame individually colored by hand.

Innovations

The film showcases several of Méliès' pioneering technical innovations, most notably the substitution splice technique that creates the magical transformations. This involved stopping the camera, making changes to the scene, and then restarting filming, creating the illusion of instantaneous transformation. The mechanical shower apparatus represented an achievement in prop engineering, designed to create multiple water effects that appeared to defy gravity and logic. The film also demonstrates Méliès' mastery of multiple exposure techniques, though the extent of their use in this particular short is debated. When hand-colored, the film represented the labor-intensive process of stencil coloring, which Méliès helped perfect and scale for commercial production. The film's construction as a single continuous take with multiple effects demonstrates the complex choreography and timing required in early special effects filmmaking.

Music

As a silent film from 1902, 'The Colonel's Shower Bath' had no synchronized soundtrack. During initial exhibition, the film would have been accompanied by live musical performance, typically a pianist or small orchestra playing appropriate music. The choice of music would have been left to the individual exhibitor or theater musician, who would select pieces that matched the comedic and magical nature of the action on screen. Popular choices might have included light classical pieces, marches (appropriate to the military theme), or improvised comedic music. Some exhibitors might have also used sound effects created backstage or with mechanical devices to enhance the shower sounds and magical transformations, though this was not standard practice for all venues.

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic sequence where the shower apparatus completely malfunctions, spraying water in impossible directions and causing the colonel to undergo rapid transformations, representing Méliès' mastery of visual comedy and special effects

Did You Know?

- This film was released under the French title 'Le bain du colonel' and was cataloged as Star Film #376 in Méliès' production list

- The film was part of Méliès' series of military-themed comedies, which were popular with audiences due to the contemporary interest in military affairs following the Franco-Prussian War

- Like many Méliès films from this period, it was illegally copied and distributed in the United States by competing film companies, leading Méliès to establish a New York branch of Star Film

- The shower apparatus used in the film was one of Méliès' most complex mechanical props, featuring multiple hidden mechanisms for creating the various water effects

- The film was originally sold both in black-and-white and in hand-colored versions, with the colored versions costing approximately four times as much as standard prints

- Méliès himself often played the military roles in his films, though it's not definitively known if he portrays the colonel in this particular short

- The film was distributed internationally and was known in English-speaking countries as both 'The Colonel's Shower Bath' and 'The Colonel's Bath'

- This film represents Méliès' fascination with transformation scenes, which he would perfect in more famous works like 'The Man with the Rubber Head' (1901)

- The military uniform and set design were historically accurate for the period, reflecting Méliès' attention to theatrical detail

- The film was part of a batch of 12 Méliès shorts released in early 1902, all running approximately one minute each

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of individual Méliès shorts from 1902 is difficult to document, as film criticism as we know it today did not yet exist. However, trade publications of the era generally praised Méliès' films for their ingenuity and visual spectacle. The film was likely reviewed positively in publications like 'The Optical Lantern and Cinematograph Journal' and 'The Bioscope,' which regularly covered Méliès' releases. Modern film historians and scholars recognize the film as a representative example of Méliès' comedic work and his mastery of early special effects techniques. While not as studied as his more ambitious productions, it is acknowledged as an important piece in understanding Méliès' complete oeuvre and the development of early cinematic comedy.

What Audiences Thought

Early Méliès films were extremely popular with audiences of the 1900s, who marveled at the magical effects and impossible transformations. 'The Colonel's Shower Bath' would have been received as both amusing and astonishing, with viewers particularly enjoying the subversion of military authority through comedy. The film's simple premise and clear visual gags made it accessible to international audiences, contributing to its wide distribution. Audiences of the era were still discovering the possibilities of cinema, and films like Méliès' comedies helped establish expectations for what movies could offer in terms of entertainment and wonder. The hand-colored versions, when available, would have been especially popular with audiences who were willing to pay premium prices for the enhanced visual experience.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage magic traditions

- Comédie-Française theatrical comedy

- French military satire

- Music hall entertainment

- Félix Mayol's comic songs

This Film Influenced

- The Man with the Rubber Head (1901)

- The Infernal Cauldron (1903)

- The Kingdom of the Fairies (1903)

- Chelovek s kino-apparatom (1929)

- The General (1926)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in the archives of the Cinémathèque Française and has been preserved as part of the Méliès collection. Several copies exist, including both black-and-white and hand-colored versions. The film has been digitally restored and is included in various Méliès compilation releases. The preservation status is considered good for a film of this vintage, though some degradation is evident in existing prints.