The Devil in a Convent

Plot

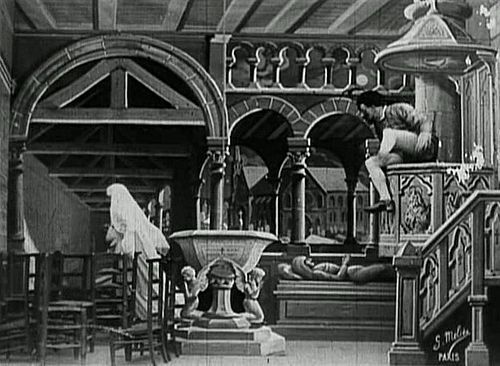

The film begins with a priest officiating a religious service in a convent chapel, surrounded by nuns who are devoutly praying. Suddenly, the priest undergoes a dramatic transformation, turning into the devil himself with horns and a grotesque appearance. The transformed devil proceeds to wreak havoc throughout the convent, chasing and terrorizing the frightened nuns who scatter in panic. The convent descends into complete chaos as the devil conjures magical effects and creates pandemonium among the holy inhabitants. The film culminates with the devil's supernatural antics completely disrupting the sacred space, transforming the peaceful religious setting into a realm of comedic horror and fantastical mayhem.

Director

Cast

About the Production

Filmed in Méliès's personal glass studio in Montreuil, which allowed for precise control of lighting and special effects. The film utilized Méliès's pioneering substitution splicing technique for the transformation sequence. The elaborate set design included a detailed convent interior backdrop painted by Méliès himself, showcasing his artistic background in stage design and magic. The devil costume and makeup were created by Méliès using theatrical techniques he had perfected during his years as a stage magician.

Historical Background

This film was created during the birth of cinema in 1899, when motion pictures were still a novelty and primarily shown as attractions in fairgrounds, music halls, and traveling exhibitions. The late 1890s marked the transition from simple actualities (filmed real events) to narrative fiction films, with Méliès leading this evolution. France was the epicenter of early cinematic innovation, with the Lumière brothers pioneering realistic documentary-style films while Méliès developed the fantasy and trick film genre. The film emerged during the Belle Époque period in France, a time of artistic flourishing and technological advancement. Religious themes were particularly resonant in late 19th-century France, which was experiencing tensions between the Catholic Church and the secular republic, making Méliès's playful treatment of religious subjects both provocative and entertaining for contemporary audiences.

Why This Film Matters

The Devil in a Convent represents a crucial milestone in the development of narrative cinema, demonstrating how early filmmakers were moving beyond simple documentation to create fictional stories with visual effects. Méliès's film helped establish horror-comedy as a viable genre in cinema, blending supernatural elements with slapstick humor. The film's use of transformation effects laid groundwork for countless horror and fantasy films that would follow. It also exemplifies the early 20th-century fascination with the supernatural and occult, reflecting broader cultural interests in spiritualism and the paranormal. The film's religious satire, while gentle by modern standards, showed early cinema's willingness to tackle taboo subjects and push social boundaries. Méliès's work, including this film, influenced the development of special effects techniques that would become fundamental to cinema, and his theatrical approach to filmmaking helped establish the grammar of cinematic storytelling.

Making Of

Georges Méliès, a former magician and theater owner, brought his expertise in theatrical illusion to this early film. The transformation scene was accomplished through meticulous frame-by-frame editing, a technique Méliès pioneered accidentally when his camera jammed and he discovered the substitution effect. The set was constructed in Méliès's glass-walled studio, which allowed natural lighting to create the ethereal atmosphere he desired. Méliès performed both the priest and devil roles himself, using quick costume changes between takes. The nuns were likely actors from Méliès's theater troupe, accustomed to his theatrical style of performance. The film was shot on 35mm film using a camera Méliès had modified from a Robert Paul projector, allowing him greater control over his special effects.

Visual Style

The cinematography reflects Méliès's theatrical background, with a single static camera positioned to capture the entire stage-like set in one continuous shot, much like a theater audience's perspective. The lighting was natural, filtered through the glass walls of Méliès's studio, creating a soft, ethereal atmosphere appropriate for the supernatural subject matter. The camera work is straightforward and functional, allowing the special effects and performances to be the focus. Méliès used deep focus to keep both foreground and background elements sharp, ensuring the elaborate set details were visible to viewers. The black and white photography creates stark contrasts that enhance the dramatic transformation from priest to devil. The framing is carefully composed to balance the religious iconography with the chaotic action, maintaining visual clarity throughout the rapid sequence of events.

Innovations

The film showcases Méliès's pioneering use of substitution splicing, a technique he discovered accidentally and perfected for creating magical transformation effects. This method involved stopping the camera, making changes to the scene or actors' costumes, then resuming filming, creating the illusion of instantaneous transformation when projected. The elaborate set construction demonstrated Méliès's ability to create detailed, theatrical environments within the constraints of early film production. The makeup and costume effects for the devil transformation were innovative for their time, using theatrical techniques adapted for the camera. The film's pacing and editing, while simple by modern standards, represented an advancement in narrative storytelling for the era. Méliès's use of multiple actors in coordinated movement showed early understanding of cinematic choreography and blocking. The film also demonstrated early special effects makeup techniques that would influence horror cinema for decades to come.

Music

As a silent film, The Devil in a Convent had no synchronized soundtrack. During its original exhibition period, the film would have been accompanied by live musical performance, typically piano or organ music. The musical accompaniment was often improvised by the venue's musician or selected from a library of appropriate pieces. For dramatic moments like the devil's transformation, musicians might have used dramatic, dissonant chords or familiar themes associated with villainy. Some exhibitors may have used sound effects created manually, such as thunder sheets or bells, to enhance the supernatural elements. Modern screenings of the film are typically accompanied by newly composed scores or period-appropriate music that reflects the film's horror-comedy tone. The absence of recorded sound emphasizes the visual nature of Méliès's storytelling and his reliance on purely cinematic techniques to convey emotion and drama.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, there are no spoken quotes, but the visual narrative communicates themes of transformation, chaos, and supernatural intervention through Méliès's signature pantomime performance style.

Memorable Scenes

- The transformation sequence where Méliès, as the priest, suddenly becomes the devil through substitution splicing - a groundbreaking special effects moment that amazed audiences of 1899 and remains historically significant as an early example of cinematic transformation effects.

Did You Know?

- This film was cataloged as Star Film Company production #185 in Méliès's extensive catalog of early films.

- The transformation sequence was achieved using Méliès's signature substitution splice technique, where he stopped the camera, replaced himself with the devil costume, then resumed filming.

- The film was part of Méliès's series of 'diabolical' films featuring the devil as a central character, which became one of his most popular recurring themes.

- Like many of Méliès's films, hand-coloring was sometimes applied to prints for special presentations, though most surviving versions are in black and white.

- The nuns in the film were likely played by male actors in drag, as was common in early French cinema due to the limited availability of female performers.

- The film demonstrates Méliès's theatrical background, with the entire action taking place on a single stage-like set reminiscent of his magic theater productions.

- At approximately 90 seconds, this was considered a relatively long film for its time, when most films were under 30 seconds.

- The devil character became one of Méliès's most iconic roles, appearing in numerous other films throughout his career.

- The film was likely shown with live musical accompaniment, typically piano or organ music composed or improvised for each screening.

- Méliès's use of religious themes and imagery was controversial for the time, though generally accepted as fantasy rather than blasphemy.

What Critics Said

Contemporary reception of Méliès's films was generally positive, with audiences and exhibitors marveling at his innovative special effects and imaginative storytelling. The film was well-received as part of Méliès's catalog of trick films, which were highly sought after by exhibitors worldwide. French trade publications of the era praised Méliès's technical ingenuity and theatrical flair. Modern film historians and critics recognize The Devil in a Convent as an important example of early narrative cinema and Méliès's mastery of cinematic illusion. The film is now studied as a representative work of early horror-comedy and as evidence of cinema's rapid evolution from simple novelty to sophisticated storytelling medium. Critics today appreciate the film's historical significance and its role in establishing many cinematic conventions that continue to influence filmmaking.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary audiences were reportedly delighted and amazed by Méliès's transformation effects and fantastical storytelling. The film was popular in both French and international markets, as evidenced by its distribution through Star Film Company's extensive catalog. Viewers of the era, unaccustomed to cinematic special effects, found the devil transformation particularly astonishing and magical. The film's blend of religious imagery with supernatural comedy appealed to the broad entertainment tastes of turn-of-the-century audiences who enjoyed spectacle and novelty. The relatively short runtime made it ideal for variety show programming, where it could be screened alongside other short attractions. Modern audiences viewing the film in retrospectives and film festivals appreciate its historical significance and charming primitive effects, often finding humor in its theatrical style and obvious stage-bound production methods.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage magic and theatrical illusion

- Gothic literature

- Religious iconography

- Commedia dell'arte

- French theatrical traditions

- Melodrama

- Folk tales about the devil

- Religious satire literature

This Film Influenced

- The Haunted Castle (1896)

- The House of the Devil (1896)

- The Damnation of Faust (1898)

- Bluebeard (1901)

- A Trip to the Moon (1902)

- The Kingdom of the Fairies (1903)

- The Infernal Cauldron (1903)

- The Merry Frolics of Satan (1906)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in various archives, including the Cinémathèque Française and other film preservation institutions. Multiple copies and versions exist, some with hand-coloring. The film has been restored and digitized as part of various Méliès retrospectives and is included in several home video collections of early cinema. While some deterioration is evident in surviving prints, the film is considered well-preserved for its age and remains accessible to scholars and the public.