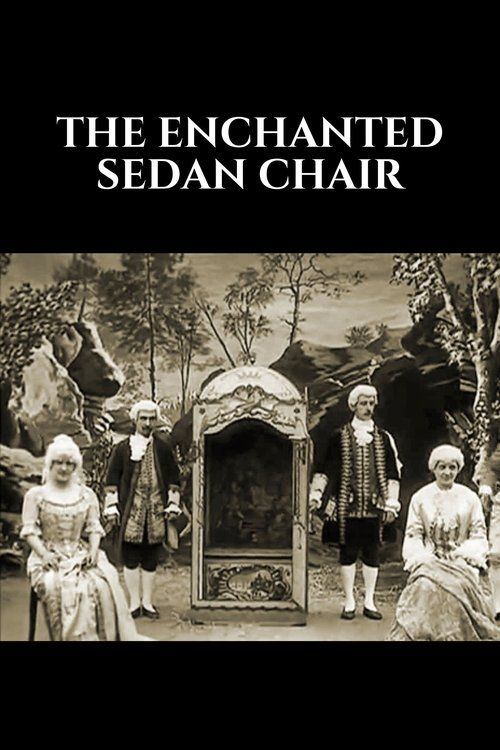

The Enchanted Sedan Chair

Plot

In this whimsical fantasy short, a court magician performs a series of magical transformations before an audience. He begins by materializing an elegant costume from within a transparent glass container, demonstrating his supernatural powers. Following this feat, a refined dandy character appears, seemingly summoned by the magician's art. The magician then conjures forth an ornate palanquin (sedan chair), which materializes out of thin air with theatrical flourish. The film culminates with the magician's mysterious intentions revealed as he places the dandy into the enchanted sedan chair, suggesting a magical journey or transformation about to unfold, embodying Méliès' signature blend of stage magic and cinematic illusion.

Director

About the Production

Filmed in Méliès's glass studio in Montreuil, which allowed for natural lighting and the elaborate set construction required for his fantasy films. The production utilized Méliès's pioneering multiple exposure techniques and substitution splices to create the magical materialization effects. The sedan chair prop was likely constructed in Méliès's workshop, where he built many of his own sets and props. The film was shot on 35mm film using a hand-cranked camera, typical of the era.

Historical Background

The Enchanted Sedan Chair was produced in 1905, during a pivotal period in cinema's development. This was the era when films were transitioning from simple actualities and trick films to more complex narrative forms. In France, the Belle Époque was in full swing, characterized by artistic innovation, technological progress, and a fascination with magic and the supernatural. Méliès's films reflected this cultural moment, combining theatrical traditions with new cinematic possibilities. The film was made just a few years after the Great Paris Exhibition of 1900, which had showcased many technological wonders and fed public appetite for magical entertainment. At this time, cinema was still primarily a novelty attraction shown in fairgrounds and music halls, and Méliès was one of the few filmmakers treating it as an art form capable of elaborate storytelling and visual spectacle.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents an important milestone in the development of fantasy and special effects cinema. Méliès's work, including The Enchanted Sedan Chair, established many conventions of the fantasy genre that would influence filmmakers for decades. The film demonstrates how early cinema could create impossible visions that theater could not achieve, showcasing the unique power of the medium. Méliès's influence can be traced through the works of later fantasy and science fiction filmmakers, from the German Expressionists to modern directors like Tim Burton and Terry Gilliam. The film also represents the cross-pollination of theatrical magic and cinematic technology, showing how performance traditions adapted to new media. As one of over 500 films Méliès created, it contributed to establishing cinema as a vehicle for imaginative storytelling rather than just documentary recording.

Making Of

The Enchanted Sedan Chair was created during what many consider the peak of Georges Méliès's creative period (1902-1906). Méliès, a former theatrical magician, brought his stage experience to cinema, treating each film as a magical performance. The glass container effect would have required precise timing - Méliès would stop the camera, place the costume in the container, then restart filming to create the illusion of spontaneous materialization. The sedan chair's appearance likely used the same substitution technique combined with smoke effects for added theatricality. Méliès's studio in Montreuil was essentially a theater space with a glass roof, allowing him to use natural lighting while maintaining complete control over his productions. The film was shot on a single camera setup, with all effects created in-camera rather than in post-production, as editing technology was virtually nonexistent at the time.

Visual Style

The cinematography in The Enchanted Sedan Chair reflects Méliès's characteristic theatrical approach. The film was shot using a static camera positioned to capture the entire stage-like set, allowing audiences to see all the magical transformations clearly. Méliès used deep focus to ensure both foreground and background elements remained sharp, essential for his complex visual effects. The lighting would have been primarily natural, coming through the glass roof of his studio, creating the bright, even illumination typical of his work. The film employed multiple exposure techniques to create the materialization effects, requiring precise timing and camera control. The composition is deliberately theatrical, with actors positioned as if on a stage rather than using naturalistic framing.

Innovations

The Enchanted Sedan Chair showcases several of Méliès's pioneering technical innovations. The film features sophisticated substitution splices, where Méliès would stop the camera, make changes to the scene, then resume filming to create the illusion of instantaneous transformation. The materialization effects required precise multiple exposure techniques, allowing objects to appear seemingly from nowhere. Méliès also employed dissolves and fade-outs to enhance the magical atmosphere. The film demonstrates his mastery of in-camera effects, as post-production editing was extremely limited in 1905. The creation of the transparent glass container effect involved careful manipulation of props and timing, representing an early form of what would become known as practical effects in cinema.

Music

As a silent film from 1905, The Enchanted Sedan Chair was originally presented without a synchronized soundtrack. During initial screenings, the film would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small orchestra playing popular pieces of the era or improvising to match the on-screen action. The musical accompaniment would have emphasized the magical elements with dramatic flourishes during the transformation scenes. In modern restorations and presentations, contemporary composers often create new scores using period-appropriate instruments and styles. Some versions may feature classical pieces from the early 1900s that were commonly used in cinema exhibitions of the time.

Memorable Scenes

- The magical materialization of the elegant costume from within the transparent glass container, showcasing Méliès's mastery of substitution effects and theatrical timing

- The dramatic appearance of the ornate sedan chair materializing from thin air, complete with smoke effects and elaborate visual flourish

Did You Know?

- This film was released by Méliès's Star Film Company and was cataloged as number 658-659 in their production list

- The film showcases Méliès's signature substitution splice technique, which he perfected through his background as a stage magician

- Like many of Méliès's films, it was hand-colored frame by frame for special releases, though most surviving copies are in black and white

- The transparent glass container effect was achieved using careful timing and multiple exposures, a technique Méliès pioneered

- Méliès played the role of the magician himself, as he did in many of his films

- The film was part of Méliès's series of court and royal-themed fantasies that were popular in the early 1900s

- At 3 minutes, this was considered a relatively long film for its time, when most films were under 2 minutes

- The dandy character represents the bourgeois class that was often satirized in French entertainment of the period

- The sedan chair (palanquin) was a symbol of exoticism and luxury in early 20th century French culture

- This film was likely exported internationally through Méliès's American and British distribution networks

What Critics Said

Contemporary reception of Méliès's films was generally positive, with audiences and critics marveling at his magical effects and imaginative scenarios. Trade publications of the era, such as The Optical Lantern and Cinematograph Journal, frequently praised Méliès's technical innovations. However, by 1905, some critics were beginning to find Méliès's theatrical style dated as filmmakers like the Lumière brothers and Edwin S. Porter were developing more realistic narrative approaches. Modern film historians and critics recognize The Enchanted Sedan Chair as representative of Méliès's mature style, though it's considered less innovative than his groundbreaking works like A Trip to the Moon (1902). The film is now appreciated for its role in establishing the fantasy genre and demonstrating early cinematic special effects techniques.

What Audiences Thought

Early 20th century audiences were captivated by Méliès's magical films, which were popular attractions at fairgrounds and music halls throughout Europe and America. The Enchanted Sedan Chair would have been received as a delightful piece of visual magic, with viewers marveling at the seemingly impossible transformations. The film's courtly setting and elegant imagery appealed to the bourgeois audiences who frequented early cinema venues. However, as cinema evolved toward more complex narratives, audiences began to prefer films with stronger story development over pure spectacle. Modern audiences viewing the film today often appreciate it as a historical artifact and a demonstration of early cinematic creativity, though its simple plot and primitive effects may seem quaint compared to contemporary fantasy films.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage magic traditions

- Victorian theatrical productions

- Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin's magic performances

- Fairy tale literature

- Commedia dell'arte

This Film Influenced

- Later fantasy films by Méliès

- German Expressionist fantasy films

- Disney's animated fantasy shorts

- Terry Gilliam's visual style

- Tim Burton's gothic fantasies

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Like many of Méliès's films, The Enchanted Sedan Chair has survived through various prints and fragments. The film exists in the archives of several institutions including the Cinémathèque Française and the Museum of Modern Art. Some versions show signs of deterioration typical of early nitrate film, but preservation efforts have helped maintain this important work of early cinema. Hand-colored versions may exist in specialized collections, though most surviving copies are in black and white. The film has been digitally restored as part of various Méliès retrospectives and collections.