The Four Troublesome Heads

Plot

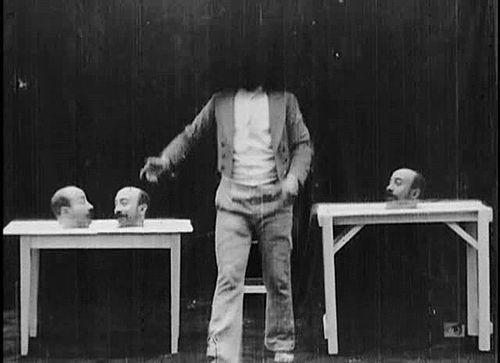

In this groundbreaking early film, Georges Méliès portrays a magician who performs an astonishing illusion before an audience. He begins by removing his own head and placing it on a table, where it continues to sing along with his body. He then removes his head a second time, creating a second detached head that also sings, and finally removes it a third time, resulting in three identical heads singing in unison on the table while Méliès stands before the audience with his head perfectly intact. The film concludes with the magician bowing to the audience, having demonstrated his seemingly impossible magical abilities through the innovative use of cinematic special effects.

Director

Cast

About the Production

Filmed in Méliès's glass-walled studio in Montreuil, which allowed natural lighting. The film was created using multiple substitution splices, where the camera was stopped, the scene altered, and filming resumed. Méliès performed all roles himself, requiring precise timing and positioning between takes. The heads were likely created using mannequins or actors positioned behind the table, with careful masking techniques.

Historical Background

The year 1898 was a pivotal moment in early cinema, just three years after the Lumière brothers' first public screening in 1895. During this period, filmmakers were experimenting with the possibilities of the new medium, moving beyond simple documentary-style recordings of real events. Georges Méliès, a former magician, was at the forefront of these experiments, transforming cinema from a novelty for capturing reality into a medium for creating fantasy and illusion. This film emerged during the Belle Époque in France, a period of artistic innovation and technological advancement. The Spanish-American War was raging, and the Dreyfus Affair was dividing French society, but Méliès's films offered audiences an escape into worlds of magic and wonder. The film industry was still in its infancy, with most films being short actualities or simple trick films like this one, typically shown as part of variety programs in music halls and fairgrounds.

Why This Film Matters

'The Four Troublesome Heads' represents a crucial milestone in the development of cinematic language and special effects. It demonstrates one of the earliest uses of multiple exposure and substitution splicing techniques that would become fundamental to visual effects cinema. The film helped establish the concept that cinema could create impossible realities, not just document existing ones, paving the way for the entire fantasy and science fiction genres. Méliès's work influenced generations of filmmakers, from early pioneers like Edwin S. Porter to modern directors like Martin Scorsese and Terry Gilliam. The film's theatrical approach to performance and its emphasis on visual spectacle over narrative complexity reflected the transition from stage magic to cinematic magic. This particular film, along with Méliès's other works, helped establish France as a center of early film production and artistic innovation, contributing to the country's lasting influence on global cinema.

Making Of

The creation of 'The Four Troublesome Heads' showcased Georges Méliès's innovative approach to filmmaking, drawing directly from his background as a stage magician. The film was shot in Méliès's custom-built studio in Montreuil, which featured glass walls and ceilings to maximize natural lighting - essential for the multiple exposure techniques he employed. The special effects were achieved through meticulous planning and execution of substitution splices, where Méliès would stop the camera, alter the scene by adding or removing elements (in this case, his own head or a prop head), and then resume filming. This required absolute precision in positioning and timing, as any slight movement would ruin the illusion. Méliès performed all roles himself, likely using a combination of mannequin heads and carefully timed appearances to create the effect of multiple detached heads. The film's theatrical presentation, with Méliès bowing at the end, reflects his roots in stage magic and his understanding of audience expectations for magical performances.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'The Four Troublesome Heads' is characterized by its static camera position and theatrical staging, typical of Méliès's early films. The camera remains fixed throughout, capturing the scene as if from a theater audience's perspective. The visual style is deliberately stage-like, with Méliès performing directly to the camera as if to a live audience. The lighting was natural, coming through the glass walls of Méliès's studio, creating a bright, even illumination that was necessary for the multiple exposure techniques. The film's visual effects were achieved in-camera through substitution splicing rather than through post-production manipulation. The composition is carefully arranged to clearly show the magical transformation while maintaining the illusion of a continuous performance. Some versions of the film were hand-colored, adding another layer of visual appeal to the already striking effects.

Innovations

The primary technical achievement of 'The Four Troublesome Heads' is its pioneering use of substitution splicing to create the illusion of multiple heads. This technique involved stopping the camera, making changes to the scene, and then restarting filming to create seemingly impossible transformations. Méliès's mastery of this technique allowed him to appear multiple times in the same frame, a revolutionary concept in 1898. The film also demonstrates early use of multiple exposure techniques, where different takes were combined to create a single composite image. The precise timing required for these effects was remarkable for the period, as any misalignment would break the illusion. The film also showcases Méliès's understanding of masking techniques to hide the mechanics of the effects. These innovations laid the groundwork for countless special effects techniques that would follow in cinema history.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Four Troublesome Heads' had no synchronized soundtrack when originally released. However, it would have been accompanied by live music during screenings, typically piano or organ music that complemented the magical nature of the film. The musical accompaniment would have been chosen to enhance the sense of wonder and to provide rhythmic support for the synchronized singing of the multiple heads. Modern screenings of the film often feature newly composed scores or period-appropriate music to recreate the original viewing experience. Some contemporary presentations use sound effects to emphasize the magical moments, though this was not part of the original 1898 presentation. The film's brief runtime meant that musical accompaniment would have been relatively simple but crucial to the overall impact of the performance.

Famous Quotes

(Silent film - no dialogue, but the performance includes synchronized singing from the multiple heads)

Memorable Scenes

- The moment when Méliès removes his head for the first time and places it on the table, where it continues to sing independently

- The reveal of all three detached heads singing in unison while Méliès stands with his head intact

- The final bow where Méliès acknowledges the audience after demonstrating his magical abilities

Did You Know?

- This film is also known by its French title 'Un homme de têtes' and sometimes translated as 'The Man with the Heads' or 'The Multi-Headed Man'

- The film demonstrates Méliès's pioneering use of substitution splicing, a technique he discovered accidentally when his camera jammed and then restarted

- Méliès was a professional magician before becoming a filmmaker, which explains his focus on magical themes and illusions

- The film was cataloged as No. 146 in Méliès's Star Film Company catalog

- The multiple heads effect was achieved by filming the same scene multiple times with different configurations, then splicing the footage together

- This film represents one of the earliest examples of a performer appearing multiple times in the same frame

- The singing heads were likely synchronized through Méliès's own performance, as the film was silent and would have had live musical accompaniment

- Méliès's glass studio allowed him to control lighting conditions precisely, which was crucial for the special effects techniques he employed

- The film was hand-colored in some releases, a common practice for Méliès's more popular films

- This short film exemplifies the theatrical, stage-like presentation that characterized much of Méliès's early work

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of Méliès's films was generally positive, with audiences and reviewers marveling at the seemingly impossible effects he achieved. The film was praised in trade publications of the era for its cleverness and technical innovation. Modern critics and film historians recognize 'The Four Troublesome Heads' as a significant work in the development of special effects cinema. It is frequently cited in film studies as an early example of the creative possibilities of editing and multiple exposure techniques. The film is now regarded as a classic of early cinema, demonstrating Méliès's mastery of the medium and his understanding of its potential for creating visual magic. Contemporary scholars often analyze the film in the context of Méliès's broader body of work and his role in establishing cinema as a medium for fantasy and spectacle rather than just documentation.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1898 were reportedly astonished and delighted by Méliès's magical films, including 'The Four Troublesome Heads.' The illusion of multiple heads appearing and singing simultaneously was considered revolutionary and magical to viewers who had never seen such cinematic tricks before. The film was popular in both France and internationally, as evidenced by its distribution through Méliès's Star Film Company and its appearance in various international markets. Modern audiences viewing the film today often express admiration for the creativity and technical ingenuity demonstrated in such an early work, despite the obvious limitations of the technology of the time. The film continues to be screened at film festivals, museums, and special retrospectives of early cinema, where it consistently receives positive responses for its historical importance and enduring charm.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage magic and illusion shows

- Theatrical performances

- Photographic trick techniques

- Lantern slide shows with special effects

- Méliès's background as a magician at the Théâtre Robert-Houdin

This Film Influenced

- The Man with the Rubber Head (1901)

- The Melomaniac (1903)

- The Infernal Cauldron (1903)

- The Kingdom of the Fairies (1903)

- Multiple exposure techniques in later films

- Modern fantasy and special effects cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in various archives and collections, including the Cinémathèque Française. Multiple versions exist, including some with hand-coloring. The film has been restored and digitized by various film preservation organizations and is considered to be in good preservation condition for a film of its age. It is included in numerous collections of early cinema and is widely available for study and viewing.