The Hallucinations of Baron Munchausen

Plot

The film begins with Baron Munchausen returning home after an evening of excessive wining and dining, clearly intoxicated. His servants struggle to help him to bed as he stumbles and slurs his words. Once finally asleep, the Baron enters a bizarre dream world where reality completely dissolves into nightmarish hallucinations. In his dreams, he witnesses impossible transformations, grotesque creatures emerging from furniture, and his own body contorting in unnatural ways. The dream sequences grow increasingly surreal and frightening, culminating in a chaotic climax where the Baron fights to escape his own subconscious. The film ends with the Baron abruptly waking up, relieved to find himself back in the safety of his bedroom, though visibly shaken by his nocturnal adventures.

Director

About the Production

This film was one of Méliès's later works, created during a period when his career was declining due to competition from other filmmakers and changing audience tastes. The film showcases Méliès's continued mastery of special effects and trick photography, though with a darker tone than his more famous early fantasy films. The production utilized multiple exposure techniques, substitution splices, and elaborate stage machinery to create the hallucinatory sequences. Méliès himself played the role of Baron Munchausen, continuing his tradition of starring in his own productions.

Historical Background

The year 1911 marked a transitional period in cinema history. The film industry was rapidly professionalizing, with longer narrative features beginning to replace the short films that had dominated early cinema. Méliès, once at the forefront of cinematic innovation, found himself increasingly out of step with evolving tastes and new filmmaking techniques. The rise of realistic narrative cinema, particularly through the influence of Danish and Italian films, was making Méliès's theatrical, fantasy-based style seem dated to contemporary audiences. Additionally, 1911 was just three years before World War I would dramatically reshape European society and culture. This film's darker tone may reflect Méliès's awareness of changing times and his own declining fortunes in the film industry.

Why This Film Matters

While not as celebrated as Méliès's earlier masterpieces like 'A Trip to the Moon' (1902), 'The Hallucinations of Baron Munchausen' represents an important evolution in the director's artistic vision. The film's exploration of psychological horror and dream imagery anticipated surrealist cinema by over a decade, predating Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí's 'Un Chien Andalou' (1929). The use of intoxication as a narrative device to justify surreal imagery would become a recurring trope in avant-garde cinema. The film also demonstrates Méliès's adaptability as a filmmaker, showing his willingness to explore darker themes even as his commercial success waned. Today, it stands as a testament to Méliès's enduring creativity and his role in expanding the vocabulary of cinematic expression beyond mere spectacle.

Making Of

The production of 'The Hallucinations of Baron Munchausen' took place in Méliès's glass studio in Montreuil, which had been his creative headquarters since 1897. By 1911, Méliès was working with a smaller crew and more limited resources than in his peak years. The film's elaborate hallucination sequences required precise timing and coordination between Méliès (as both director and actor) and his small team of technicians. The transformation effects were achieved through multiple exposure photography, requiring the camera to be cranked back and reloaded for each layer of the composite image. The set design incorporated numerous trap doors and hidden mechanisms to create the appearance of objects and creatures appearing and disappearing. Méliès's performance as the drunken Baron was reportedly physically demanding, as it required him to simulate intoxication while still maintaining the precise positioning needed for the trick photography effects.

Visual Style

The cinematography, handled by Méliès himself using his custom-built camera, showcases the director's mastery of in-camera special effects. The film employs multiple exposure techniques to create ghostly overlays and impossible transformations. Substitution splices are used extensively for the appearance and disappearance of objects and creatures. The camera work is static, typical of the era, but the frame is filled with dynamic action and visual effects. The lighting design creates dramatic contrasts between the mundane bedroom setting and the fantastical dream sequences. Méliès's use of forced perspective and clever set design enhances the surreal quality of the hallucinations. The black and white photography emphasizes the chiaroscuro effects, particularly in the darker horror sequences.

Innovations

The film demonstrates Méliès's continued innovation in special effects photography, particularly in his use of multiple exposure to create layered dream imagery. The substitution splices used for transformations and disappearances were executed with remarkable precision, especially considering the manual nature of film editing in 1911. The film's set design incorporated numerous mechanical effects and trap doors to create the appearance of objects and creatures emerging from unexpected places. Méliès's use of forced perspective and matte painting techniques enhanced the surreal quality of the hallucination sequences. The film also showcases sophisticated editing techniques for its time, including jump cuts and cross-fading to create dream-like transitions between scenes.

Music

As a silent film from 1911, 'The Hallucinations of Baron Munchausen' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The specific musical selections would have been left to the discretion of individual theater musicians or pianists, though they typically used classical pieces or popular melodies of the era. For the more intense hallucination sequences, musicians might have employed dissonant or dramatic music to enhance the horror elements. No original score or specific musical cues were composed for the film, as was standard practice for productions of this period. Modern screenings of the film often feature newly composed scores or carefully selected period-appropriate music to accompany the visuals.

Famous Quotes

(Silent film - no dialogue) The film's narrative is conveyed entirely through visual storytelling and intertitles, with no spoken dialogue.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where the drunken Baron struggles with his servants, establishing the premise for his subsequent hallucinations. The transformation sequence where furniture and household objects come to life and morph into grotesque creatures. The climactic hallucination where multiple versions of the Baron appear simultaneously, creating a nightmarish mirror effect. The final awakening scene where the Baron sits up abruptly in bed, his face showing relief mixed with lingering terror from his dream experience.

Did You Know?

- This film represents one of Méliès's rare forays into horror territory, contrasting with his more typical fantasy and adventure themes.

- The Baron Munchausen character was based on the German literary figure known for impossible adventures and tall tales, making him a perfect subject for Méliès's surreal style.

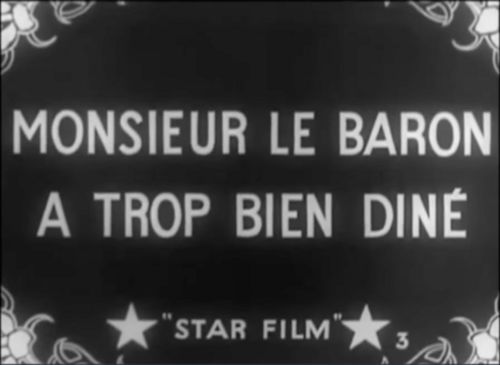

- The film was released as Star Film catalog number 1562-1564, indicating it was originally sold as three separate scenes or reels.

- Unlike many of Méliès's earlier films that were hand-colored, this production was primarily released in black and white.

- The hallucination sequences were created using techniques Méliès had pioneered over a decade earlier, including multiple exposures and substitution splices.

- This film came during a difficult period for Méliès, whose company was facing financial difficulties and losing market share to competitors.

- The film's darker, more psychological themes were unusual for Méliès, who typically focused on more whimsical fantasy content.

- Some historians consider this film a precursor to surrealist cinema, with its dream logic and bizarre imagery.

- The Baron's drunken state at the beginning serves as a narrative justification for the subsequent surreal sequences.

- Méliès's use of the Baron Munchausen character predates the more famous 1943 German film by Josef von Báky by over three decades.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of the film is difficult to document due to the limited film journalism of the era. However, trade publications of the time noted that while Méliès's technical wizardry remained impressive, audiences were becoming less enthusiastic about his style of fantasy films. Modern film historians and critics have reassessed the work more favorably, recognizing it as an important example of early horror cinema and a precursor to surrealist film techniques. Scholars particularly praise the film's sophisticated use of dream logic and its departure from Méliès's more straightforward fantasy narratives. The film is now viewed as a significant work in understanding Méliès's artistic evolution and the broader transition from early cinema's theatrical influences to more psychologically complex storytelling.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception in 1911 appears to have been modest at best, reflecting the general decline in popularity that Méliès was experiencing during this period. Contemporary audiences, increasingly accustomed to more realistic narratives and longer films, found Méliès's theatrical style and short format less appealing than they had in the early 1900s. The film's darker horror elements may have been too intense for some viewers accustomed to Méliès's more whimsical fantasies. Modern audiences, when able to view the film through screenings of preserved copies or digital releases, tend to appreciate it as a fascinating example of early cinematic horror and Méliès's technical ingenuity. The film's brevity and visual spectacle make it particularly accessible to contemporary viewers interested in the history of cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The literary Baron Munchausen stories

- Gothic horror literature

- Symbolist art movement

- Surrealist precursors in literature

- Stage magic traditions

This Film Influenced

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

- Un Chien Andalou (1929)

- The Fall of the House of Usher (1928)

- Early surrealist and experimental cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved, with some elements surviving in various film archives. A complete version may exist, but access is limited. The film has been restored and digitized by several film preservation organizations, including the Cinémathèque Française. Some color-tinted versions are known to exist, though most surviving copies are in black and white. The film is part of the Méliès collection that was rediscovered in the 1940s, bringing many of the director's lost works back to public attention.