The Infernal Cauldron

Plot

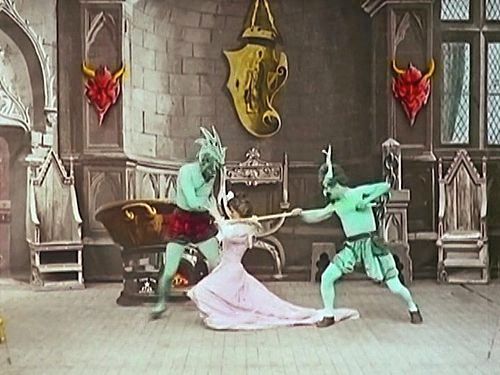

In this early fantasy-horror short, a green-skinned demon with horns emerges from a theatrical backdrop and approaches a group consisting of a woman and two courtiers. The demon magically compels the woman to dance against her will before seizing her and the two male companions. He places all three victims into a large cauldron that bursts into flames, and after stirring the contents with a pitchfork, the demon extracts their skeletons which he then reassembles into living beings. The film concludes with the transformed victims dancing under the demon's command before he ultimately vanishes in a puff of smoke.

Director

Cast

About the Production

Filmed in Méliès' glass-walled studio in Montreuil using his signature theatrical backdrops and special effects techniques. The cauldron scene required multiple exposures and careful timing of pyrotechnic effects. Méliès painted the scenery himself and used his extensive collection of theatrical props and costumes. The transformation effects were achieved through substitution splicing and careful editing.

Historical Background

The year 1903 represented a pivotal moment in early cinema, with filmmakers transitioning from simple actualities to narrative fiction films. Georges Méliès, a former magician, was at the forefront of this transformation, creating fantastical narratives that exploited cinema's potential for illusion. This period saw the rise of permanent film theaters and the establishment of film as a legitimate entertainment medium. The film emerged during the Belle Époque in France, a time of artistic innovation and cultural optimism, though it also reflected contemporary fascination with the supernatural and occult that was prevalent in European society. Méliès' work was particularly influential in establishing the fantasy and horror genres in cinema.

Why This Film Matters

The Infernal Cauldron represents a crucial early example of the horror genre in cinema, predating many of the conventions that would later define horror filmmaking. Méliès' use of transformation and magical effects established visual tropes that would influence generations of horror and fantasy filmmakers. The film's depiction of demonic forces and supernatural transformation tapped into Victorian-era anxieties about the occult while showcasing cinema's unique ability to render the impossible visible. As one of over 500 films Méliès created, it exemplifies his pioneering approach to narrative cinema and special effects, contributing to the development of film language itself. The work also demonstrates early cinema's role in translating theatrical and magical traditions to the new medium of film.

Making Of

Georges Méliès filmed this short in his purpose-built glass studio in Montreuil, which allowed him to control lighting conditions for his complex special effects. The demon makeup required hours of application, and Méliès would often perform in multiple takes due to the technical demands of the effects sequences. The skeleton transformation involved creating papier-mâché skeleton costumes that could be worn over the actors, then removed during editing to create the illusion of reassembly. The cauldron flames were created using cotton soaked in alcohol, lit carefully between takes. Méliès' background as a magician at the Théâtre Robert-Houdin heavily influenced his approach to cinematic illusions, treating the camera as an extension of his stage magic techniques.

Visual Style

The cinematography reflects Méliès' theatrical background, with static camera positions and compositions reminiscent of stage presentations. The film was shot using a single camera positioned to capture the entire scene, allowing audiences to witness the magical transformations without distraction. Méliès employed multiple exposure techniques to create the appearance and disappearance effects, while substitution splicing enabled the transformation sequences. The lighting was carefully controlled in his glass studio to ensure the visibility of the special effects and maintain consistent exposure across the multiple takes required for the complex sequences. The visual style emphasizes spectacle over realism, with painted backdrops and theatrical props creating a deliberately artificial world.

Innovations

The film showcases Méliès' mastery of early special effects techniques, particularly substitution splicing and multiple exposure. The skeleton transformation sequence required precise timing and careful editing to create the illusion of magical reassembly. The pyrotechnic effects in the cauldron scene demonstrated Méliès' innovative approach to creating dangerous-looking effects safely. The film also features sophisticated makeup and costume effects for the demon character, which were groundbreaking for the period. Méliès' use of painted backdrops and theatrical props represented an early form of production design that would influence later narrative cinema. The disappearance effect at the film's conclusion utilized a puff of smoke effect that became one of Méliès' signature techniques.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Infernal Cauldron' was originally accompanied by live musical performance, typically piano or organ music. The specific musical scores were not standardized, leaving accompaniment to the discretion of individual theater musicians. Méliès' films were often accompanied by dramatic, classical-style music that emphasized the supernatural elements of the narrative. Some venues employed narrators or 'bonimenteurs' who would explain the action to audiences, particularly for films with complex visual effects. Modern restorations typically feature newly composed scores that attempt to capture the spirit of early 20th-century cinema accompaniment.

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic transformation sequence where the demon extracts skeletons from the cauldron and magically reassembles them into living beings, a technical marvel of early cinema that showcases Méliès' mastery of substitution splicing and multiple exposure techniques.

Did You Know?

- This film was released as 'Le Chaudron Infernal' in France and cataloged as Star Film #433-434

- The demon character was one of Méliès' most frequent roles, appearing in numerous films throughout his career

- The skeleton transformation sequence was considered particularly advanced for its time, requiring precise multiple exposure techniques

- Méliès' green makeup was created using theatrical greasepaint, which was notoriously difficult to remove

- The film was hand-colored in some releases, a laborious process where each frame was individually painted

- Like many Méliès films, it was designed to be shown with live musical accompaniment and possibly a narrator

- The cauldron prop was reused in several other Méliès productions, including 'The Kingdom of the Fairies'

- This film was part of Méliès' series of 'demon' films that were particularly popular with audiences

- The dance sequences were choreographed by Méliès himself, who had background in theater performance

- The film was distributed internationally, with copies sent to the United States through Méliès' American distribution network

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews from 1903 praised the film's spectacular effects and Méliès' performance as the demon. The trade journal 'The Optical Lantern and Cinematograph Journal' noted the 'ingenious transformation scenes' and 'masterful use of pyrotechnics.' French critics of the period recognized Méliès as a leading innovator in cinematic spectacle, though some dismissed his work as mere trickery rather than art. Modern film historians and critics have reevaluated Méliès' work, recognizing 'The Infernal Cauldron' as an important early horror film and a significant example of primitive cinema's artistic ambitions. Scholars particularly note the film's sophisticated use of multiple exposure and substitution splicing techniques.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1903 reportedly responded enthusiastically to the film's shocking imagery and magical effects. The demon character and the transformation sequences were particularly popular with viewers, who were still amazed by cinema's ability to create impossible visions. The film was a commercial success in both French and international markets, where Méliès had established distribution networks. Contemporary accounts describe audiences gasping at the skeleton transformation sequence and applauding the final disappearance effect. The film's blend of horror and spectacle appealed to the working-class audiences who frequented early cinema venues, while its technical sophistication impressed more sophisticated viewers.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage magic and illusion shows

- Gothic literature

- Theatrical melodrama

- Opera and ballet

- Occult and demonology texts

- Phantasmagoria shows

This Film Influenced

- Later horror films featuring demonic transformations

- Fantasy films with magical effects

- Surrealist cinema of the 1920s

- German Expressionist horror films

- Modern fantasy special effects sequences

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in multiple copies, including hand-colored versions, and has been preserved by various film archives including the Cinémathèque Française and the Museum of Modern Art. Several restoration projects have been undertaken to preserve and digitize existing prints, with the most comprehensive restoration completed in the early 2000s as part of a broader Méliès film preservation initiative. The film is considered to be in good preservation condition for its age, though some deterioration is evident in surviving prints.