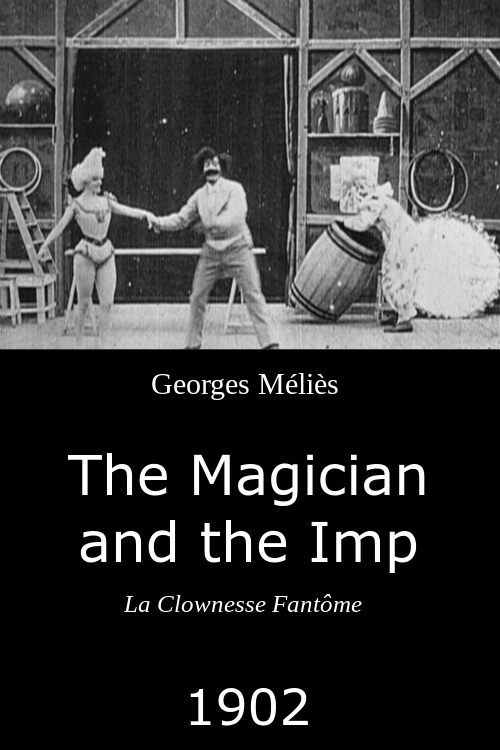

The Magician and the Imp

Plot

In this early trick film, a magician takes the stage accompanied by his impish assistant. The imp holds a simple piece of cloth, which the magician magically transforms into a beautiful woman dressed in tights through Méliès' signature substitution splice technique. A barrel is then brought onto the stage, and the newly created girl enters one end of the barrel. The magician continues his magical performance, demonstrating the seemingly impossible transformations that characterized Méliès' cinematic magic shows.

Director

About the Production

Filmed in Méliès's glass studio in Montreuil-sous-Bois, which allowed for natural lighting and contained elaborate stage sets. The film was created using Méliès's pioneering special effects techniques, particularly substitution splices for the transformation effects. Like many of Méliès's films from this period, it was designed to replicate the experience of watching a stage magic show but with the added possibilities of cinema.

Historical Background

1902 was during the golden age of early cinema, when filmmakers were still discovering the unique possibilities of the medium. Georges Méliès was at the height of his creative powers during this period, having established himself as the premier filmmaker of fantasy and trick films. This was the same year Méliès released his most famous work, 'A Trip to the Moon.' The film was created during an era when cinema was transitioning from simple actualities to narrative fiction, and magic tricks were among the most popular subjects. The film reflects the theatrical origins of cinema, with Méliès adapting stage magic illusions for the new medium.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents an important example of early cinematic special effects and the adaptation of theatrical magic to film. Méliès's work laid the groundwork for the fantasy and science fiction genres in cinema. His techniques influenced generations of filmmakers and established many conventions of visual effects that continue to this day. The film demonstrates how early cinema could create illusions impossible in live theater, establishing cinema as a medium with its own unique magical capabilities. Méliès's work represents the birth of cinematic fantasy and the understanding that film could transport audiences to impossible realms.

Making Of

The film was created using Méliès's innovative substitution splice technique, where the camera would be stopped, objects or actors would be changed, and filming would resume. This created the illusion of instantaneous transformation. Méliès discovered this technique accidentally when his camera jammed and he found that objects appeared to change when he resumed filming. The sets were elaborate theatrical constructions in his glass-walled studio, and the performances were staged as if for a live theater audience. The actors were likely drawn from Méliès's regular troupe of performers from the Théâtre Robert-Houdin.

Visual Style

The film features Méliès's characteristic theatrical style with static camera positions and elaborate stage sets. The cinematography emphasizes the magical transformations through careful timing of the substitution splices. The visual style is deliberately theatrical, with the camera positioned as if it were an audience member watching a stage performance. The lighting would have been natural light from the glass studio, creating a bright, clear image suitable for the detailed magical effects.

Innovations

The film showcases Méliès's pioneering use of substitution splices for transformation effects. This technique involved stopping the camera, making changes to the scene, and then resuming filming to create the illusion of instantaneous transformation. The film also demonstrates Méliès's mastery of multiple exposures and careful editing to create magical effects. These techniques were groundbreaking for their time and established the foundation for modern visual effects.

Music

As a silent film, it would have been accompanied by live music during exhibition. The musical accompaniment would typically have been provided by a pianist or small orchestra, often playing popular tunes of the era or specially composed pieces to match the magical action on screen. The music would have emphasized the mysterious and fantastical elements of the performance.

Memorable Scenes

- The magical transformation of the cloth into a beautiful woman using substitution splices, which would have appeared as genuine magic to early cinema audiences

Did You Know?

- This film is part of Méliès's extensive catalog of trick films, which numbered over 500 during his career

- The film was released by Méliès's Star Film company and was assigned catalog number 424

- Like many early films, it was hand-colored in some versions, a practice Méliès employed for many of his works

- The transformation from cloth to woman was achieved using substitution splices, one of Méliès's signature techniques

- Méliès often played the magician role himself in his films, though this is not definitively confirmed for this particular film

- The film would have been shown alongside other short films in early cinema programs

- Many of Méliès's films from this period were exported internationally, particularly to the United States

- The imp character was a recurring motif in Méliès's magical films, representing supernatural assistance

- The barrel trick was a common stage magic illusion that Méliès adapted for the cinema medium

- Early cinema audiences were often amazed by these transformation effects, which seemed like genuine magic

What Critics Said

Contemporary reception of Méliès's films was generally positive, with audiences marveling at the magical effects. Critics of the time praised his ingenuity and the seemingly impossible transformations he achieved on screen. Modern film historians recognize Méliès as a pioneering figure in cinematic special effects and fantasy filmmaking. The film is now studied as an important example of early cinematic techniques and the development of visual effects language.

What Audiences Thought

Early cinema audiences were reportedly amazed and delighted by Méliès's trick films. The transformation effects would have appeared as genuine magic to viewers unfamiliar with film techniques. The films were popular attractions in fairgrounds and early cinemas, with Méliès's magical fantasies being among the most sought-after subjects. The combination of theatrical spectacle and cinematic possibility made these films particularly appealing to turn-of-the-century audiences.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage magic performances

- Théâtre Robert-Houdin

- Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin's magic shows

- Theatrical illusion traditions

This Film Influenced

- Later trick films by other directors

- Fantasy films of the silent era

- Modern transformation sequences in cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Many of Méliès's films were lost due to neglect and the melting of his film stock for raw materials. However, copies of several of his 1902 films have survived in various archives around the world, including the Cinémathèque Française and other film preservation institutions. The film exists in the Méliès collection and has been restored by various film archives.