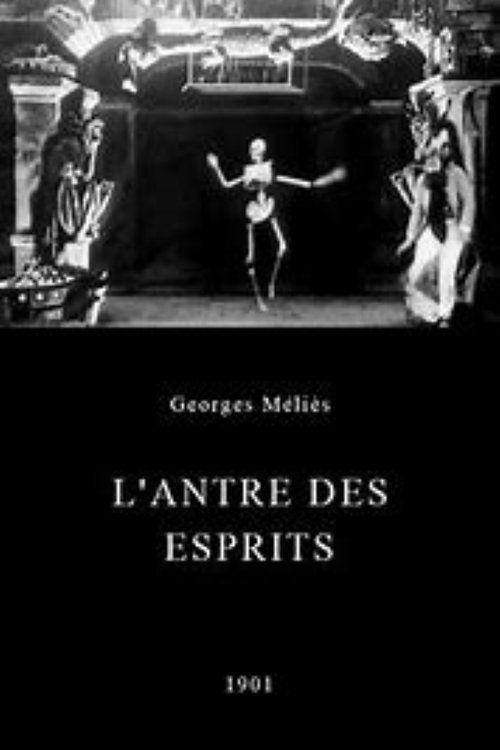

The Magician's Cavern

Plot

In this early trick film, Georges Méliès portrays an enthusiastic magician who performs a series of spectacular illusions within his mysterious cavern. The magician begins by conjuring various objects from thin air, transforming them into different items, and making them disappear with theatrical flair. As the performance escalates, he creates multiple assistants from thin air, each of whom performs their own magical feats. The climax features the magician transforming himself into various forms and ultimately disappearing in a puff of smoke, leaving the audience in wonder at the impossible spectacle they have witnessed.

Director

Cast

About the Production

Filmed in Méliès's glass-walled studio in Montreuil using natural lighting. The film employed multiple exposure techniques, substitution splices, and stage machinery to create the magical effects. Méliès painted elaborate backdrops and constructed the cavern set himself, as was his custom for all productions.

Historical Background

In 1901, cinema was still in its infancy, with films typically lasting only a few minutes and shown as part of vaudeville programs. Georges Méliès was one of the few filmmakers treating cinema as an art form rather than just a novelty. This period saw the rise of narrative cinema, with Méliès leading the way in fantasy and special effects. The film industry was largely unregulated, with copyright protection minimal, leading to widespread piracy that would eventually harm Méliès financially. France was the center of early cinema production, with Pathé and Gaumont dominating the industry alongside Méliès's Star Film Company.

Why This Film Matters

The Magician's Cavern represents an important milestone in the development of special effects cinema and fantasy filmmaking. Méliès's work laid the groundwork for future generations of filmmakers interested in creating impossible visions on screen. The film exemplifies the transition from stage magic to cinematic magic, showing how the new medium could create illusions impossible in live theater. Méliès's influence can be seen throughout film history, from the early fantasy films of the 1920s to modern special effects blockbusters. His films were among the first to demonstrate cinema's potential for pure imagination and spectacle.

Making Of

Georges Méliès, a former professional magician, brought his theatrical expertise to cinema with this film. He constructed the elaborate cavern set in his glass studio in Montreuil, using painted backdrops and theatrical props. The magical transformations were achieved through Méliès's innovative use of multiple exposure, substitution splices, and careful editing. As was his practice, Méliès performed as the magician himself, drawing on his years of stage experience. The film was shot in a single day, as was typical for Méliès's short films of this period, with his wife Jeanne d'Alcy often assisting with costumes and props.

Visual Style

The film was shot using a single stationary camera, typical of the era, with Méliès employing a proscenium-style composition reminiscent of theater. The cinematography emphasized the magical effects through careful framing and timing. Méliès used painted backdrops and theatrical lighting to create the cavern atmosphere. The camera work was straightforward, allowing the special effects to take center stage without distracting camera movement.

Innovations

The film showcases Méliès's pioneering use of multiple exposure to create magical transformations and appearances. He employed substitution splices, where the camera was stopped and objects or people were changed between shots, creating the illusion of instantaneous transformation. The film also demonstrates Méliès's mastery of stage machinery and theatrical effects adapted for cinema. These techniques, while primitive by modern standards, were revolutionary for 1901 and established many principles still used in special effects today.

Music

As a silent film, The Magician's Cavern would have been accompanied by live music during its original screenings. This typically included piano or small orchestra arrangements, often improvising based on the action on screen. Méliès sometimes provided suggested musical cues with his films, though specific scores for this production have not survived. The music would have emphasized the magical elements and dramatic moments of the performance.

Famous Quotes

(Silent film - no dialogue, but intertitles may have included phrases like 'Behold! The Great Magician!' and 'Watch as the impossible becomes reality!')

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic sequence where the magician transforms himself into various forms before disappearing in a puff of smoke, demonstrating Méliès's mastery of substitution splices and multiple exposure techniques

Did You Know?

- This film was released by Méliès's Star Film Company and cataloged as number 312 in their production list

- The film was hand-colored in some releases, a labor-intensive process where each frame was individually painted

- Like many Méliès films, it was likely shown with live musical accompaniment, often piano or small orchestra

- The film was exported internationally, including to the United States where Méliès had established distribution

- Méliès often played the magician role himself in his films, drawing on his actual experience as a professional magician

- The cavern set was one of Méliès's most elaborate studio constructions, featuring painted rock formations and theatrical lighting effects

- This film was part of Méliès's series of magic trick films, which were extremely popular with audiences of the time

- The film was shot on 35mm film at approximately 16 frames per second, standard for the era

- Many of Méliès's films from this period were pirated by American producers, leading to his financial struggles

- The transformation effects were achieved through careful timing and multiple exposure techniques that Méliès pioneered

What Critics Said

Contemporary reception of Méliès's films was generally enthusiastic, with audiences marveling at the impossible tricks and transformations. Critics of the time praised Méliès's ingenuity and theatrical flair. Modern film historians recognize The Magician's Cavern as a significant example of early special effects work and Méliès's contribution to cinematic language. The film is now studied as an important artifact of early cinema, demonstrating the primitive yet innovative techniques that would evolve into modern visual effects.

What Audiences Thought

Early 20th century audiences were captivated by Méliès's magical films, which represented a form of entertainment unlike anything they had seen before. The Magician's Cavern, like other Méliès productions, was popular both in France and internationally. Audiences particularly enjoyed the theatrical presentation and the sense of wonder created by the impossible transformations. The film was often shown repeatedly due to popular demand, as viewers tried to figure out how the tricks were accomplished.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage magic traditions

- Theatrical conjuring acts

- Victorian magic shows

- Parisian theater productions

This Film Influenced

- Later Méliès fantasy films

- Early Disney animation

- Harry Potter film series

- The Prestige (2006)

- The Illusionist (2006)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in various archives, including the Cinémathèque Française and the Museum of Modern Art. Some versions exist in their original hand-colored form. The film has been restored and digitized as part of various Méliès retrospectives and is considered well-preserved for a film of its age.