The Man with the Rubber Head

Plot

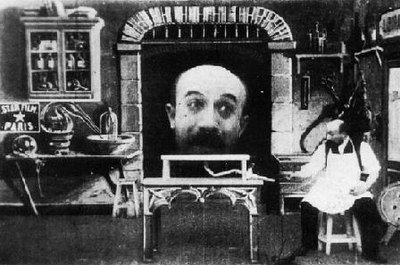

A chemist in his laboratory removes his own head and places it on a table, where it becomes rubber-like and expandable. He demonstrates his creation by inflating the head with a bellows, making it grow to enormous proportions before it explodes. The chemist frantically tries to reassemble his head, eventually succeeding by using a pump to restore it to normal size. The film concludes with the chemist proudly displaying his reattached head, having survived his bizarre scientific experiment.

Director

Cast

About the Production

Filmed in Méliès's glass-walled studio which allowed natural lighting. The film utilized multiple exposure techniques and substitution splices to create the illusion of the detachable head. Méliès himself performed all the effects and acted in the film, which was typical of his productions. The rubber head prop was carefully constructed to appear both realistic and comically flexible.

Historical Background

This film was created during the pioneering years of cinema, when filmmakers were still discovering the medium's possibilities. In 1901, films were typically shown as part of vaudeville programs or in traveling exhibitions, and most were under two minutes long. The film industry was in its infancy, with France leading in artistic innovation through filmmakers like Méliès and the Lumière brothers. This period saw the development of narrative cinema and the first uses of special effects, moving away from simple actuality films toward more creative and fantastical content. The film emerged from the Belle Époque era in France, a time of great artistic and cultural flourishing in Paris.

Why This Film Matters

The Man with the Rubber Head represents a crucial milestone in cinematic history as one of the earliest examples of special effects-driven storytelling. It demonstrates cinema's potential to create impossible scenarios that could never be performed on stage, establishing the medium as a unique art form rather than merely recorded theater. The film's success helped establish the fantasy genre in cinema and influenced countless future filmmakers working with special effects. Méliès's techniques in this film, particularly the multiple exposure and substitution splicing, became foundational tools for cinematic illusion. The film also represents the transition from magic theater to cinema, showing how Méliès adapted his stage magic skills for the new medium.

Making Of

Georges Méliès created this film in his custom-built glass studio in Montreuil-sous-Bois, which he designed specifically for filming his magical effects. The production involved careful choreography and timing to execute the multiple exposure effects that made the head appear to detach and grow. Méliès, a former magician, applied his knowledge of stage illusions to cinema, using substitution splices - where the camera is stopped, objects are changed, and filming resumes - to create seamless magical transformations. The rubber head prop was constructed with varying sizes to show the inflation effect, and the explosion was created using a different prop designed to burst apart on cue. The entire film was shot in a single day, as was typical for Méliès's short films of this period.

Visual Style

The cinematography was typical of Méliès's style, featuring a single static camera position that captured the entire action as if viewing a stage performance. This theatrical approach allowed Méliès to execute his complex special effects with precision. The film utilized multiple exposure techniques to create the illusion of the head detaching from the body, and careful editing to show the head's transformation. The lighting was natural, coming through the glass walls of Méliès's studio, creating a bright, clear image that was necessary for the special effects to work properly. Some versions of the film were hand-colored, adding to its visual appeal and magical quality.

Innovations

This film showcased several groundbreaking technical innovations including multiple exposure photography, substitution splicing, and careful prop construction. Méliès's use of multiple exposure allowed him to create the illusion of the head existing separately from the body. The substitution splice technique, where filming was stopped to change elements in the scene, enabled the magical transformations. The film also demonstrated early understanding of continuity editing and visual storytelling. The construction of the rubber head prop with multiple sizes for the inflation sequence was an innovative approach to creating visual effects through practical means.

Music

The film was originally silent, as was standard for all films in 1901. When exhibited, it would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small orchestra playing appropriate music to enhance the comedic and magical elements. The musical accompaniment would have varied by venue and performer, with some exhibitors using popular tunes of the day while others composed original pieces. Modern screenings often feature newly composed scores that attempt to capture the whimsical and magical nature of the film.

Famous Quotes

No dialogue was present in this silent film

Memorable Scenes

- The iconic moment when the chemist inflates his detached head using a bellows, watching it grow to enormous proportions before dramatically exploding, sending pieces flying across the laboratory

Did You Know?

- This film is also known by its French title 'L'homme à la tête de caoutchouc'

- The film demonstrates Méliès's pioneering use of multiple exposure and substitution splicing techniques

- The exploding head effect was achieved through careful editing and the use of a different prop for the explosion sequence

- Méliès often played the lead role in his own films, and this is one of his most famous performances

- The film was part of Méliès's series of 'trick films' that showcased his innovative special effects

- The rubber head prop was reportedly made from papier-mâché and painted to resemble skin

- This film was distributed internationally and was one of Méliès's most commercially successful works

- The film's concept was inspired by stage magic acts popular in Paris at the time

- Méliès patented many of the techniques used in this film, including the substitution splice

- The film was hand-colored in some releases, a common practice for important Méliès productions

What Critics Said

Contemporary reception was overwhelmingly positive, with audiences and exhibitors marveling at the impossible effects Méliès achieved. The film was praised for its technical innovation and comedic appeal. Modern critics recognize it as a masterpiece of early cinema and a prime example of Méliès's genius. Film historians consider it one of the most important early examples of special effects cinema, often citing it as evidence of Méliès's role as the 'cinemagician.' The film is frequently studied in film courses as an example of early special effects techniques and the development of cinematic language.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with audiences of its time, who had never seen such magical effects on screen before. Viewers were reportedly amazed and sometimes frightened by the illusion of the detachable, expanding head. The film became one of Méliès's most requested works for exhibition and was shown extensively throughout Europe and America. Its success led to increased demand for Méliès's fantasy films and helped establish his reputation as the leading filmmaker of fantastical cinema. Modern audiences viewing the film today often express admiration for its creativity and technical ingenuity, considering it remarkably sophisticated for its era.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage magic acts of the late 19th century

- Sideshow performances

- Scientific demonstrations

- Comedic theater traditions

- The works of Jules Verne

This Film Influenced

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

- Frankenstein (1931)

- The Fly (1958)

- Scanners (1981)

- Being John Malkovich (1999)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved and restored by various film archives including the Cinémathèque Française. Multiple copies exist in different film archives worldwide. Some versions retain the original hand-coloring. The film is considered well-preserved for its age and is frequently included in retrospectives of early cinema and Méliès's work.