The Mysterious Knight

Plot

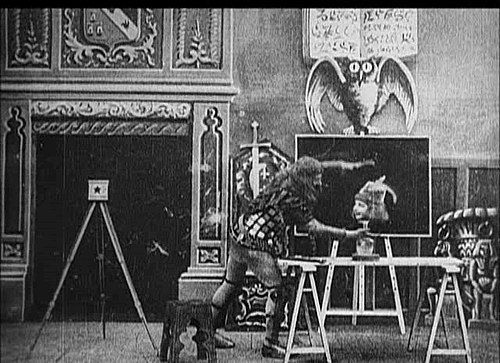

In this early fantasy short film, a mysterious knight enters a room and begins performing magical tricks. He draws a face on a chalkboard, which then magically transforms into a living, disembodied head that floats in mid-air. The knight continues to showcase his supernatural abilities by making the head appear and disappear, demonstrating Méliès' pioneering special effects techniques. The film culminates with various magical transformations that would have astonished audiences of the late 19th century, showcasing the boundless possibilities of the new medium of cinema.

Director

Cast

About the Production

Filmed in Méliès's glass-walled studio which allowed natural lighting. The film utilized multiple exposure techniques and substitution splices to create the magical effects. Méliès personally hand-colored some prints of his films during this period, though it's unknown if this specific film received color treatment.

Historical Background

The Mysterious Knight was created in 1899, during the pioneering years of cinema when the medium was still discovering its artistic potential. This was just four years after the Lumière brothers' first public film screening in 1895. The late 1890s saw the emergence of narrative cinema, moving away from simple actualities and staged scenes toward more complex storytelling. France was at the center of cinematic innovation, with Méliès and the Lumière brothers representing two different approaches to the new medium. The Belle Époque period in France was characterized by technological optimism and fascination with magic and spiritualism, themes that heavily influenced Méliès's work. Cinema was primarily exhibited in fairgrounds, music halls, and traveling shows rather than dedicated theaters.

Why This Film Matters

The Mysterious Knight represents an important milestone in the development of cinematic language and special effects. Méliès's work, including this film, helped establish cinema as a medium for fantasy and imagination rather than just documentary realism. His innovative techniques, particularly the substitution splices and multiple exposures used in this film, became foundational tools in cinematic special effects that would influence filmmakers for generations. The film exemplifies the transition from stage magic to cinematic magic, showing how the new medium could create illusions impossible in live theater. Méliès's fantasy films like this one helped establish the genre of science fiction and fantasy in cinema, paving the way for future filmmakers from Fritz Lang to George Lucas.

Making Of

Georges Méliès created this film in his custom-built studio in Montreuil-sous-Bois, which featured glass walls and ceilings to maximize natural lighting. The production involved meticulous planning of special effects, particularly the substitution splices used to create the appearance and disappearance of the disembodied head. Méliès would stop the camera, replace objects or actors, then resume filming to create magical transformations. The knight costume and props were likely created in Méliès's workshop, where he designed and built all his film's sets and costumes. The filming process was extremely primitive by modern standards, with Méliès manually cranking his camera and performing all the special effects in-camera without post-production editing capabilities.

Visual Style

The cinematography in The Mysterious Knight is characteristic of Méliès's theatrical style, featuring a single, static camera position that captures the entire scene as if watching a stage performance. The camera was positioned to capture the full theatrical space Méliès constructed in his studio. The lighting relied primarily on natural light from the glass studio, supplemented by artificial lighting when necessary. The film's visual style is highly theatrical, with painted backdrops and stage-like composition that reflects Méliès's background in theater and magic.

Innovations

The Mysterious Knight showcases several of Méliès's pioneering technical innovations, most notably the substitution splice technique used to create magical appearances and disappearances. The film also demonstrates early use of multiple exposure to create the effect of the disembodied head. These in-camera effects were revolutionary for their time and represented some of the first examples of cinematic special effects. Méliès's ability to precisely time these effects without the benefit of modern editing equipment demonstrates his technical mastery and understanding of the new medium's possibilities.

Music

As a silent film from 1899, The Mysterious Knight had no synchronized soundtrack. During original exhibition, the film would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small orchestra playing appropriate mood music. The musical accompaniment would have varied by venue and could have included popular songs of the era or improvised pieces. Some exhibitors might have used sound effects created manually to enhance the magical elements of the film.

Memorable Scenes

- The magical transformation of the chalkboard drawing into a living, disembodied head that floats independently in space, demonstrating Méliès's mastery of special effects and his ability to bring the impossible to life on screen.

Did You Know?

- This film was released during the very dawn of cinema, when films were still considered novelties rather than art forms

- The film showcases Méliès's mastery of substitution splices, a technique he pioneered and perfected

- Méliès often played the lead roles in his own films, believing he could best execute the precise timing required for his special effects

- The disembodied head effect was achieved through multiple exposure techniques that Méliès developed

- This film was cataloged as Star Film No. 181 in Méliès's production list

- Many of Méliès's films from this period were illegally copied and distributed in America by Thomas Edison and others without compensation

- The film would have been originally shown as part of a traveling magic lantern show or fairground attraction

- Méliès was a professional magician before becoming a filmmaker, which heavily influenced his cinematic style

- The chalkboard drawing sequence demonstrates Méliès's interest in bringing inanimate objects to life through cinema

- This film represents Méliès's fascination with the supernatural and magical transformation themes

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of Méliès's films in 1899 was limited, as film criticism as we know it today did not exist. Reviews appeared primarily in trade papers and magic journals, where Méliès's films were praised for their magical effects and novelty. Modern critics and film historians recognize The Mysterious Knight as an important example of early cinematic special effects and Méliès's contribution to developing the language of cinema. The film is now studied for its technical innovations and its role in establishing cinema as a medium for fantasy and imagination.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1899 were typically astonished by Méliès's magical films, which were unlike anything they had seen before. The disembodied head effect would have been particularly impressive to viewers unfamiliar with cinematic techniques. These films were extremely popular at fairgrounds and music halls, where they were often presented as part of larger variety shows. Méliès's films were successful enough to sustain his production company for over a decade, indicating strong audience demand. Modern audiences viewing the film today appreciate it primarily for its historical significance and the ingenuity of its special effects given the technological limitations of the era.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage magic and illusion shows

- Theater traditions

- Fairy tales and folklore

- Spiritualism movement of the late 19th century

This Film Influenced

- Later Méliès films such as 'The Man with the Rubber Head' (1901)

- The fantasy and science fiction films of the early 20th century

- Modern special effects cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in archives, though like many Méliès films, some copies may be incomplete or deteriorated. The Méliès family collection and various film archives worldwide preserve copies of his work. The film has been included in various DVD collections and digital restorations of Méliès's films.