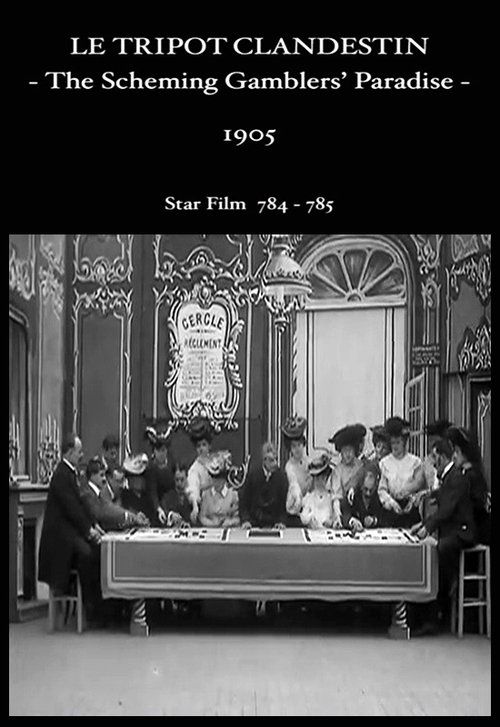

The Scheming Gambler's Paradise

Plot

The film depicts a cleverly designed establishment that serves as both a gambling den and bawdy house, where croupiers, patrons, prostitutes, and the owner work in concert. When police raids are imminent, the entire operation undergoes a rapid transformation, with gambling equipment quickly hidden and the space converted into a legitimate mercantile establishment. The film showcases the ingenuity of the establishment's operators as they fool authorities through their quick-change tactics. This comedic scenario highlights the cat-and-mouse game between illegal operations and law enforcement in early 20th century urban settings. The transformation sequence likely employed Méliès' signature substitution splices and stage magic techniques.

Director

About the Production

This film was likely shot in Méliès' glass-walled studio in Montreuil-sous-Bois, using theatrical sets and props. The transformation sequence would have required precise choreography and multiple takes to achieve the seamless effect. Méliès typically used substitution splices for such magical transformations, stopping the camera, changing the scene, then resuming filming. The film would have been hand-colored frame by frame, a laborious process that Méliès' studio employed for many of their productions.

Historical Background

1905 was a pivotal year in early cinema, occurring during the transition from novelty attractions to narrative storytelling. The film was produced during the Belle Époque in France, a period of cultural flourishing despite social tensions. Urban vice and police corruption were common themes in popular entertainment, reflecting real social concerns. Méliès was competing with emerging filmmakers like the Lumière brothers and Pathé, who were developing different approaches to cinema. This period also saw the rise of nickelodeons in America, creating new markets for short films. The film's themes of deception and transformation resonated with audiences fascinated by modernity's illusions.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents Méliès' contribution to the development of narrative cinema and special effects. The transformation techniques pioneered in such films influenced generations of filmmakers and established visual effects as a cinematic language. The film reflects early 20th century attitudes toward vice and authority, using comedy to critique social hypocrisies. Méliès' work helped establish cinema as a medium for fantasy and spectacle, moving beyond mere documentation to imaginative storytelling. The film's survival and study today provides insight into early 20th century popular culture and the evolution of cinematic techniques.

Making Of

The production would have taken place in Méliès' innovative glass studio, designed to maximize natural light for filming. The transformation sequence required meticulous planning, with actors and props positioned precisely for the substitution splice effect. Méliès, drawing from his theatrical background, would have directed his performers with exaggerated gestures suitable for silent cinema. The hand-coloring process involved dozens of workers applying color to each frame individually. The gambling props and mercantile goods would have been custom-built for the production, designed for quick removal and replacement during the transformation sequence.

Visual Style

The film would have employed Méliès' characteristic theatrical staging, with fixed camera positions and deep focus to capture the entire stage space. The cinematography emphasized clarity and composition, allowing audiences to follow the transformation sequence. Lighting would have been primarily natural, augmented by artificial sources when needed. The visual style remained rooted in theatrical traditions while exploring cinema's unique possibilities for magical effects and impossible transformations.

Innovations

The film's primary technical achievement was the seamless transformation sequence, accomplished through substitution splices. This technique involved stopping the camera, changing the scene, then resuming filming to create magical effects. The precision required for such effects was remarkable for 1905. The hand-coloring process, though labor-intensive, added visual appeal and helped distinguish Star Film productions. The film represents the refinement of Méliès' special effects techniques, which he had been developing since the late 1890s.

Music

As a silent film, it would have been accompanied by live music during exhibition, typically piano or organ in theaters. The musical accompaniment would have been improvised or selected from available repertoire to match the on-screen action. No original score was composed for the film, as was standard practice for productions of this era. The music would have emphasized the comedic aspects and heightened the tension during the transformation sequence.

Famous Quotes

No dialogue - silent film

Memorable Scenes

- The rapid transformation sequence where the gambling den and brothel instantly convert into a legitimate mercantile establishment as police approach, showcasing Méliès' signature substitution splice effects and clever stagecraft

Did You Know?

- Georges Méliès was a former magician who brought stage magic techniques to cinema, revolutionizing visual effects

- In 1905, Méliès was at the peak of his productivity, creating dozens of short films

- The film likely featured Méliès himself in one of the roles, as he frequently acted in his own productions

- Star Film Company numbered their releases rather than using consistent titles, leading to confusion in film identification

- Many Méliès films from this period were hand-colored by women workers in his studio using stencils

- The transformation effects were achieved through substitution splices, a technique Méliès pioneered

- Early cinema censorship was beginning to emerge, making films about vice establishments controversial

- Méliès' films were popular globally, with distribution networks reaching America, Britain, and beyond

- The film would have been shown in fairgrounds, music halls, and dedicated nickelodeons

- Méliès' brother Gaston managed the American distribution of Star Film productions

What Critics Said

Contemporary reception is difficult to document, but Méliès' films were generally popular with audiences and critics in the early 1900s. Trade publications of the era typically praised his technical innovations and imaginative scenarios. Modern film historians recognize Méliès as a pioneer of cinematic language and special effects. The film is valued today for its historical significance and technical achievements, representing an important stage in the development of narrative cinema and visual effects techniques.

What Audiences Thought

Early cinema audiences were fascinated by Méliès' magical effects and transformation sequences. The combination of risqué subject matter with clever visual tricks would have appealed to turn-of-the-century viewers seeking both spectacle and mild titillation. Méliès' films were popular across social classes, shown in venues ranging from fairground attractions to more respectable theaters. The film's themes of outsmarting authority would have resonated with working-class audiences familiar with police interference in their leisure activities.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage magic and theatrical illusions

- Commedia dell'arte traditions

- French café-concert entertainment

- Social realist literature

- Police procedural narratives

This Film Influenced

- Later transformation sequences in comedy films

- Gangster films featuring speakeasy transformations

- Screwball comedies with quick-change elements

- Heist films with elaborate disguises

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Many Méliès films from this period are considered lost or exist only in fragmentary form. The preservation status of this specific film is unclear, though some Méliès productions have been rediscovered and restored by film archives. The film would have existed on nitrate stock, which deteriorates over time, making survival rare. Any surviving copies would likely be held by major film archives such as the Cinémathèque Française or the Museum of Modern Art.