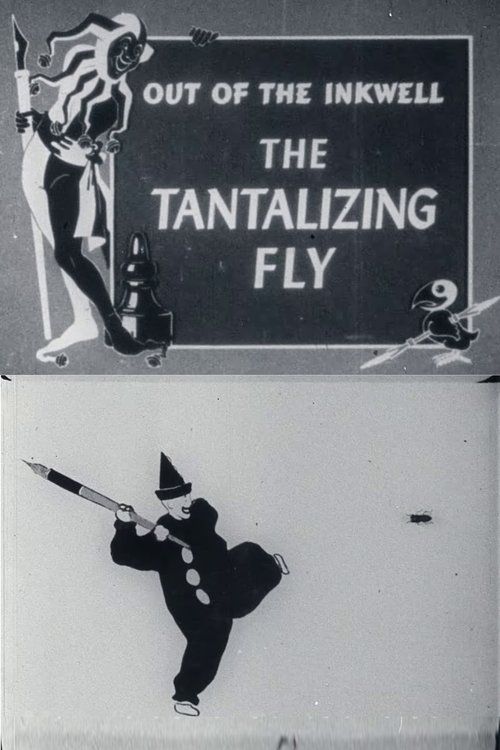

The Tantalizing Fly

Plot

In this early 'Out of the Inkwell' short, Max Fleischer draws Koko the Clown who emerges from an inkwell onto the animator's desk. A pesky fly begins to torment Koko, who desperately tries to catch it using various methods. The fly proves to be too clever for the clown, leading to increasingly frustrated and comical attempts to capture it. The animation showcases the innovative technique of combining live-action with cartoon, as the animator's hand interacts with the animated character. The film concludes with the fly ultimately outsmarting Koko, leaving the clown defeated while the fly triumphantly buzzes away.

Director

About the Production

This was one of the early entries in the groundbreaking 'Out of the Inkwell' series that pioneered the combination of live-action and animation. The series was initially produced through Bray Productions before Fleischer established his own studio. The innovative rotoscope technique, invented by Max Fleischer, was used to create more realistic character movements by tracing over live-action footage.

Historical Background

1919 was a pivotal year in animation history, occurring just after World War I when the film industry was experiencing rapid technological advancement. The animation field was still in its infancy, with pioneers like Winsor McCay, Walt Disney (just beginning his career), and the Fleischer brothers establishing the foundations of the medium. The 'Out of the Inkwell' series represented a significant leap forward in animation technology and storytelling, introducing techniques that would become industry standards. This period also saw the rise of animation as a commercial enterprise, with theaters increasingly programming animated shorts alongside feature films.

Why This Film Matters

The 'Out of the Inkwell' series, including 'The Tantalizing Fly,' was groundbreaking in its exploration of the relationship between creator and creation, reality and animation. These shorts established meta-narrative techniques that would influence generations of animators and filmmakers. The series helped establish New York as a major center for animation production, competing with the emerging Hollywood studios. Koko the Clown became one of the first recurring animated characters with a distinct personality, paving the way for character-driven animation that would dominate the medium in the following decades.

Making Of

The production of 'The Tantalizing Fly' involved the innovative process of combining live-action footage of an animator's hand with traditional cel animation. Max Fleischer would film his brother Dave's hand drawing the characters, then animators would create the cartoon sequences around this footage. The rotoscope technique was employed to achieve more fluid and realistic movements for Koko the Clown. The animation team worked in a small studio in New York, often working long hours to produce these technically complex shorts. The sound effects and musical accompaniment would have been added during theatrical exhibition, as these were silent films that relied on live musicians in theaters.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'The Tantalizing Fly' involved the innovative combination of live-action photography and traditional animation. The live-action segments were filmed using standard cameras of the era, while the animated portions were created frame by frame on paper and later transferred to cels. The technical challenge of matching the lighting and perspective between live-action and animated elements was groundbreaking for its time. The series pioneered techniques for creating the illusion of three-dimensional space within animated sequences, using perspective and depth that was advanced for 1919.

Innovations

The most significant technical achievement of this film was the seamless integration of live-action and animation using the rotoscope technique. Max Fleischer's invention allowed animators to trace over live-action footage frame by frame, creating more realistic and fluid character movements. The series also pioneered the use of peg registration for animation, ensuring consistent alignment between successive frames. The technical process of combining the animator's hand with animated characters required innovative compositing techniques that were revolutionary for 1919.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Tantalizing Fly' did not have an original synchronized soundtrack. Musical accompaniment would have been provided live in theaters by pianists or small orchestras, typically using popular songs of the era or classical pieces appropriate to the on-screen action. The fast-paced comedy of the fly chase sequences would have been accompanied by lively, syncopated music to enhance the humor. Some theaters may have used specific cue sheets provided by the distributor to guide musicians in their accompaniment choices.

Famous Quotes

The silent era nature of this film means there are no recorded spoken quotes, but the visual humor and pantomime of Koko's frustration became iconic in early animation

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Koko emerges from the inkwell, demonstrating the innovative live-action/animation technique. The climactic chase sequence where Koko employs increasingly elaborate and failed attempts to catch the fly, showcasing both physical comedy and the technical prowess of the animation. The final scene where the fly triumphantly buzzes away while Koko collapses in defeat, establishing the character's expressive personality and the series' comedic sensibility.

Did You Know?

- This film features one of the earliest appearances of Koko the Clown, who would become Max Fleischer's signature character for decades

- The 'Out of the Inkwell' series was revolutionary for its time, featuring an animator's hand interacting directly with animated characters

- Max Fleischer's brother Dave Fleischer often served as the live-action animator hand seen in the films

- The series was initially distributed by Paramount Pictures and later by Margaret Winkler

- The rotoscope technique used in these films was patented by Max Fleischer in 1917, just two years before this short

- Early 'Out of the Inkwell' films were shot on 35mm film and required hand-coloring frame by frame for certain releases

- The series was so successful that it led to the establishment of Fleischer Studios in 1921

- Koko the Clown was originally named 'Clown' and didn't get his name 'Koko' until later in the series

- The animation was drawn on paper with holes punched in it, an early version of peg registration that would become standard in animation

- These shorts were among the first to explore the fourth wall concept, with characters acknowledging their existence as drawings

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the 'Out of the Inkwell' series for its technical innovation and clever humor. Film trade publications of the era noted the remarkable seamless integration of live-action and animation as a significant achievement. The series was frequently highlighted as one of the most sophisticated animated productions of its time. Modern animation historians recognize these shorts as crucial stepping stones in the development of animation as an art form, with particular emphasis on the Fleischer brothers' technical innovations and storytelling techniques.

What Audiences Thought

The 'Out of the Inkwell' shorts were extremely popular with audiences of the late 1910s and early 1920s. Theater owners reported strong attendance for programs featuring these films, particularly among children who were fascinated by the magical appearance of characters emerging from inkwells. The series developed a loyal following that helped establish animation as a reliable draw for movie theaters. Audience letters and feedback from the period suggest that viewers were particularly enchanted by the novelty of seeing an animator's hand interact with cartoon characters.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Winsor McCay's 'Gertie the Dinosaur'

- Early comic strip animation

- Vaudeville comedy routines

- Silent film slapstick comedy

This Film Influenced

- Later 'Out of the Inkwell' entries

- Fleischer's 'Betty Boop' cartoons

- Disney's early 'Alice Comedies'

- Modern meta-animated films like 'Who Framed Roger Rabbit'

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Many of the early 'Out of the Inkwell' shorts, including 'The Tantalizing Fly,' survive in various archives and collections. The film has been preserved by the Library of Congress and other film archives. Some versions exist in restored digital formats, though quality varies depending on the source material. The UCLA Film and Television Archive maintains copies of several Fleischer shorts from this period. The film is considered historically significant and efforts have been made to preserve it for future generations.