The Untamable Whiskers

Plot

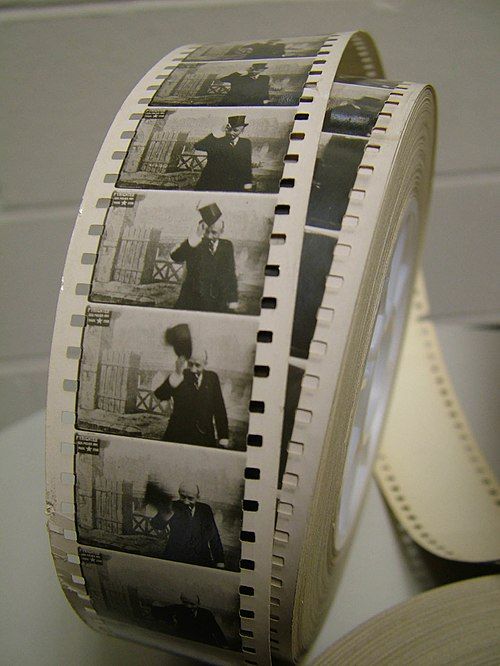

In this innovative Georges Méliès fantasy-comedy, a gentleman appears in a scenic setting along the Seine River in Paris and retrieves a blackboard from the side of the frame. He proceeds to sketch a portrait of a novelist, then magically transforms himself into the drawn character, with his own clean-shaven face being replaced by the whiskered visage he created. The transformation is executed so seamlessly that the change appears instantaneous and mysterious to the viewer. He continues this process by sketching and becoming several distinct characters: a miser, an English cockney, a comic character, a French policeman, and finally the grinning face of Mephistopheles, demonstrating Méliès' mastery of substitution splicing and visual trickery.

Director

Cast

About the Production

Filmed in Méliès's glass-walled studio in Montreuil-sous-Bois, using painted backdrops to create the illusion of the Seine River. The film showcases Méliès's pioneering use of substitution splicing, where the camera would be stopped, the actor would change costume and makeup, and filming would resume to create the transformation effect. The blackboard prop was specially designed to be easily visible to the camera and allowed for the drawn sketches to be clearly seen by the audience.

Historical Background

In 1904, cinema was still in its infancy, with films typically lasting only a few minutes and shown as part of vaudeville programs. The year saw the Russo-Japanese War, the first major conflict of the 20th century, and the beginning of the Entente Cordiale between Britain and France. In the art world, this was the period when Pablo Picasso was moving toward his Rose Period, and Henri Matisse was emerging as a leader of the Fauvist movement. Méliès was at the height of his career in 1904, having established himself as the premier creator of fantasy films in the world. His films were distributed internationally through his Star Film Company, with offices in Paris, London, and New York.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents a crucial moment in the development of cinematic special effects and narrative storytelling. Méliès's transformation techniques influenced generations of filmmakers and laid the groundwork for modern special effects cinema. The film's exploration of identity through physical transformation anticipated themes that would become central to 20th-century art and literature. As one of the early examples of an artist literally creating characters through drawing and then embodying them, it reflects the meta-artistic concerns that would become more prominent in avant-garde cinema decades later. The film also serves as a valuable document of early 20th-century social types and stereotypes, offering insight into how different classes and nationalities were perceived in French society at the time.

Making Of

The production of 'The Untamable Whiskers' exemplified Méliès's theatrical approach to filmmaking. Having been a magician and theater director before entering cinema, Méliès brought stage techniques to his films. The transformation sequences required precise timing and multiple takes to achieve the seamless substitution effects. Méliès would perform in front of a stationary camera, then the camera would be stopped while he quickly changed costumes and applied different makeup styles for each character. The painted backdrop of the Seine was created in Méliès's studio using his background in theatrical set design. The blackboard prop was carefully positioned to ensure the sketches would be clearly visible in the final print, and Méliès likely had to practice the drawing sequences multiple times to perfect the timing.

Visual Style

The cinematography, typical of Méliès's work, employed a stationary camera positioned to capture the entire theatrical space. The lighting was natural, coming through the glass walls of Méliès's studio, creating the bright, even illumination characteristic of his films. The camera work was straightforward but effective, ensuring that the transformations would be clearly visible to the audience. The painted backdrop of the Seine was designed to be visible but not distracting, allowing focus to remain on the central performer and his magical transformations.

Innovations

The film's primary technical achievement was the sophisticated use of substitution splicing to create seamless transformations. Méliès pioneered this technique, which involved stopping the camera, making changes to the scene, and then restarting filming. The precision required for these effects was remarkable for 1904, as even slight variations in camera position could ruin the illusion. The film also demonstrated Méliès's mastery of theatrical makeup and costume design, with each transformation requiring completely different facial hair and clothing that could be quickly changed between takes.

Music

As a silent film from 1904, 'The Untamable Whiskers' had no synchronized soundtrack. During initial screenings, the film would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small orchestra playing popular tunes of the era or improvising to match the on-screen action. The musical accompaniment would have varied by venue and could include anything from classical pieces to popular Parisian café music.

Famous Quotes

It is something entirely new in motion pictures and is sure to please (Méliès Catalog description)

Memorable Scenes

- The sequence of rapid transformations where Méliès changes from one character to another, culminating in the dramatic appearance of Mephistopheles with his demonic grin, representing the ultimate magical transformation from the mundane to the supernatural

Did You Know?

- This film is cataloged as Star Film #543-544 in Méliès's production catalog

- The original French title was 'Le Barbier mystérieux' (The Mysterious Barber)

- The film showcases one of Méliès's favorite themes: magical transformation through artistic creation

- The sequence of transformations represents different social types common in Parisian society of the early 1900s

- Méliès himself performed all the character transformations, requiring multiple costume and makeup changes

- The film was hand-colored in some releases, a common practice for Méliès's more popular films

- The final transformation into Mephistopheles reflects Méliès's fascination with demonic and magical themes

- The blackboard technique was innovative for its time, predating similar effects in later films by decades

- This film was part of Méliès's series of 'transformation films' that were extremely popular in the early 1900s

- The English cockney character reflects the international character of Paris at the turn of the century

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews from 1904 praised the film's technical innovation and entertainment value. Trade publications like 'The Optical Lantern and Cinematograph Journal' noted the film's 'clever use of substitution' and 'amusing character transformations.' Modern critics recognize the film as an important example of Méliès's contribution to cinematic language, with film scholar Ezra Goodman calling it 'a masterclass in early special effects that demonstrates Méliès's complete understanding of the magical potential of the new medium.' The film is frequently cited in academic studies of early cinema as exemplifying the transition from actuality films to narrative fantasy.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by audiences of its time, who were fascinated by Méliès's seemingly magical transformations. Contemporary accounts suggest that viewers were particularly impressed by the seamless nature of the changes and the variety of characters presented. The film's inclusion of recognizable social types like the English cockney and French policeman would have resonated with Parisian audiences of the period. Like many of Méliès's films from this era, it was popular both in France and internationally, being shown in music halls and fairground theaters across Europe and North America.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage magic and illusion shows

- Commedia dell'arte character types

- Parisian café-concert entertainment

- Theatrical quick-change acts

This Film Influenced

- Later transformation films by other directors

- Character transformation sequences in fantasy cinema

- Meta-cinematic works about artistic creation

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in multiple archives, including the Cinémathèque Française and the Museum of Modern Art. Some versions exist in hand-colored form, while others are black and white. The film has been restored and digitized as part of various Méliès retrospectives and is included in several DVD and Blu-ray collections of his work.