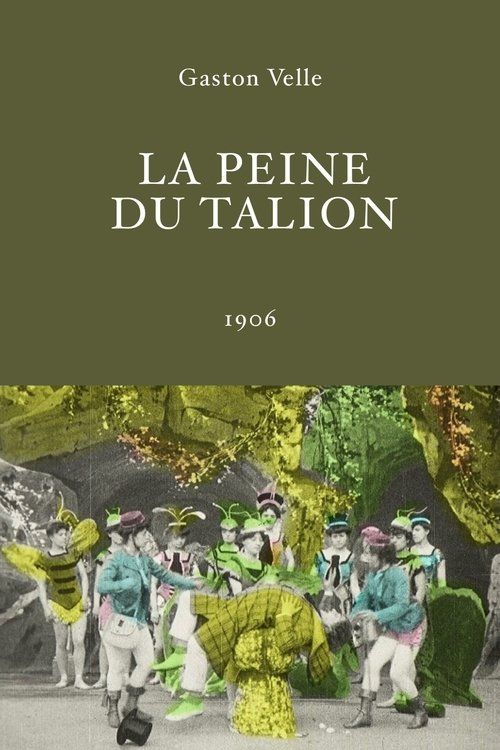

Tit-for-Tat

Plot

In this fantastical morality tale, a greedy entomologist ventures into a magical forest in pursuit of rare and valuable insects, capturing them without regard for their lives. After successfully collecting several specimens, the entomologist falls asleep and dreams that he is taken before an insect court where the creatures he has captured serve as his judges. The court finds him guilty of cruelty to insects and condemns him to a fitting punishment - he is shrunk down and pinned to a giant cork board like the specimens he collected. The film serves as a cautionary tale about the consequences of exploiting nature for personal gain, delivered through the lens of early cinematic fantasy and special effects.

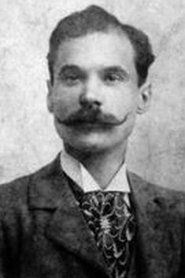

Director

About the Production

Directed by Gaston Velle, who was known as 'The French Méliès' due to his innovative use of special effects and trick photography. The film utilized stop-motion techniques, substitution splices, and forced perspective to create the illusion of the entomologist shrinking and being pinned. The giant insects were created through oversized props and clever camera angles. The production likely took place in Pathé's studio facilities in Paris or Vincennes, where many of their fantasy films were shot.

Historical Background

This film was created during the golden age of French cinema, when Pathé Frères dominated the global film market. 1906 was a pivotal year in cinema's development, as films were transitioning from simple actualities to more complex narrative and fantasy works. The era saw the rise of trick films and special effects cinema, largely pioneered in France by filmmakers like Georges Méliès and Gaston Velle. This period also coincided with growing public interest in science and natural history, making the entomological theme particularly relevant to contemporary audiences. The film's environmental message, while subtle, reflected early 20th-century concerns about industrialization's impact on nature.

Why This Film Matters

Tit-for-Tat represents an important example of early French fantasy cinema and the trick film genre that flourished before narrative features became dominant. The film demonstrates the sophisticated special effects techniques being developed in the 1900s, including substitution splices and forced perspective. Its environmental theme was remarkably ahead of its time, predating the modern environmental movement by decades. The film also illustrates the moralistic storytelling common in early cinema, where clear lessons about right and wrong were delivered through fantastical scenarios. As a work by Gaston Velle, it contributes to our understanding of this innovative but lesser-known filmmaker's contribution to early cinema history.

Making Of

Gaston Velle, who began his career as a stage magician at the Folies Bergère, brought his expertise in illusion to this film. The production required elaborate sets including oversized flowers and insects to create the dream sequence. The special effects team used multiple exposure techniques to create the appearance of the entomologist shrinking. The film was shot on Pathé's studio stages where Velle had access to some of the most advanced film equipment of the time. The actors, mostly stage performers accustomed to exaggerated gestures, had to adapt their acting style for the camera while still conveying the story clearly to silent film audiences. The production likely took only a few days to complete, which was typical for short films of this era.

Visual Style

The cinematography, likely handled by Pathé's studio cameramen, employed innovative techniques for the time. Multiple exposure photography was used to create the shrinking effect, while forced perspective gave the illusion of giant insects. The film utilized matte photography to combine live action with painted backgrounds. The camera work was static, as was typical of the era, but the composition was carefully planned to maximize the effectiveness of the special effects. The lighting was dramatic and theatrical, enhancing the dreamlike quality of the sequences.

Innovations

The film showcased several innovative special effects techniques for 1906, including substitution splices for the transformation scenes, forced perspective to create the illusion of scale difference between humans and insects, and multiple exposure photography. The production used oversized props and miniatures to enhance the fantasy elements. The film also demonstrated sophisticated matte painting techniques for background elements. These technical achievements placed Velle among the leading special effects filmmakers of his time, alongside Georges Méliès.

Music

As a silent film, 'Tit-for-Tat' would have been accompanied by live music during exhibition. The specific musical score is not documented, but theaters typically used stock music or improvisation. A pianist or small orchestra would have provided musical accompaniment that matched the on-screen action - whimsical music for the forest scenes, dramatic music for the trial, and suspenseful music for the punishment sequence. The music would have been crucial in conveying the emotional tone and helping audiences follow the narrative.

Famous Quotes

No recorded dialogue exists as this is a silent film

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic transformation sequence where the entomologist shrinks down to insect size, the insect court trial with giant creatures serving as judges, the climactic scene where the protagonist is pinned to the giant cork board, the opening sequence of the entomologist hunting rare butterflies in the enchanted forest

Did You Know?

- The film is also known by its French title 'Un drame chez les insectes' (A Drama Among the Insects)

- Director Gaston Velle was a magician before becoming a filmmaker, which explains his expertise in visual tricks and illusions

- The film was produced by Pathé Frères, one of the most important film companies of the early 20th century

- Velle's special effects techniques were influenced by and often compared to those of Georges Méliès

- The film's moral about respecting nature was relatively progressive for its time

- Only a few of Velle's films survive today, making 'Tit-for-Tat' a rare example of his work

- The giant insects in the film were likely created using oversized models and forced perspective photography

- Pathé distributed this film internationally, helping spread French cinema's influence globally

- The film was part of a series of trick films Velle made for Pathé between 1905-1907

- The cork board punishment scene was achieved through clever use of matte photography and substitution splices

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of the film are scarce, as film criticism was still in its infancy in 1906. However, trade publications of the time likely praised the film's technical innovations and visual effects. Modern film historians and scholars recognize 'Tit-for-Tat' as a significant example of early French fantasy cinema and Velle's technical skill. The film is often cited in studies of early special effects and the influence of stage magic on cinema. Critics today appreciate the film's sophisticated effects work for its time and its surprisingly progressive environmental message.

What Audiences Thought

Early 20th-century audiences were fascinated by trick films and special effects, making 'Tit-for-Tat' likely popular when it was first released. The film's clear moral message and spectacular visual effects would have appealed to the fairground and theater audiences who were the primary consumers of cinema at the time. The dream sequence and transformation effects would have been particularly impressive to viewers who had never seen such cinematic illusions before. The film's short length made it ideal for the varied programs typical of early cinema exhibitions.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Works of Georges Méliès

- Stage magic traditions

- Natural history illustrations

- Aesop's fables

- French theatrical traditions

This Film Influenced

- Later nature-themed fantasy films

- Environmental cinema

- Body transformation films

- Moral fantasy tales

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in archives and is considered preserved, though like many films of this era, it may exist in incomplete or deteriorated condition. Copies are held in film archives including the Cinémathèque Française and other major film preservation institutions. The film has been digitized as part of early cinema preservation efforts.