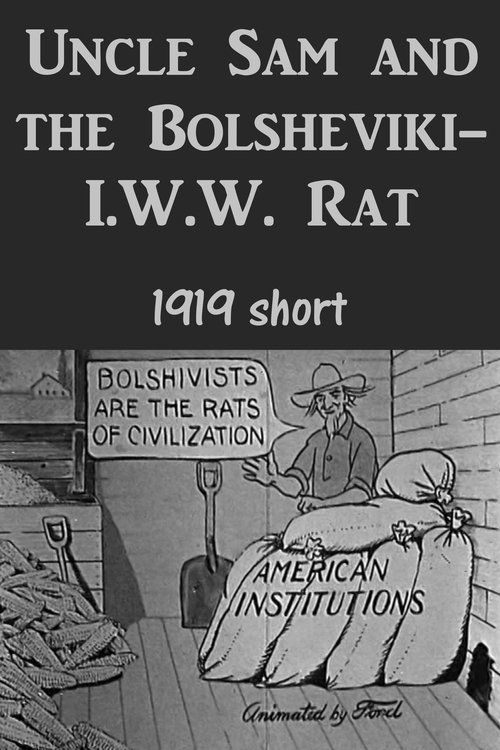

Uncle Sam and the Bolsheviki-I.W.W. Rat

Plot

In this 1919 propaganda animated short, Uncle Sam is depicted as a vigilant farmer protecting America's grain stores from a menacing giant rat branded with 'I.W.W.' (Industrial Workers of the World). The cartoon shows the Bolsheviki-I.W.W. rat attempting to devour the nation's harvest, symbolizing the perceived threat of radical labor movements and communist ideology to American prosperity and security. Uncle Sam decisively intervenes by braining the rat with a hammer, demonstrating the triumph of American values over radical influences. The film concludes with the rat defeated and America's resources secured, reinforcing the message that radical elements must be eliminated to protect the nation. This brief but powerful visual metaphor served as clear propaganda during the First Red Scare period.

About the Production

This unusual animated short was produced by Ford Motor Company, not a traditional animation studio, suggesting it was created specifically as corporate propaganda rather than entertainment. The film was likely part of Ford's anti-union messaging during a period of intense labor tensions. The animation style is typical of the era, using simple cut-out or cel animation techniques. The production was probably handled by Ford's internal advertising or promotional department rather than professional animators.

Historical Background

This film was created during the First Red Scare, a period of intense anti-communist and anti-radical hysteria that swept the United States following the Russian Revolution of 1917. The years 1919-1920 saw numerous labor strikes, bombings by anarchist groups, and widespread fear of communist infiltration. The Palmer Raids, led by Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, resulted in the arrest of thousands of suspected radicals and the deportation of many immigrants. The I.W.W. (Industrial Workers of the World) was specifically targeted during this period, with many of its leaders arrested and its headquarters raided. Industrialists like Henry Ford were particularly concerned about the spread of radical labor ideas, which threatened their control over workers. This cartoon reflects the corporate and government efforts to portray labor organizers and radicals as dangerous, un-American elements that needed to be eliminated for the good of the country.

Why This Film Matters

This film serves as an important artifact of early 20th century American propaganda and the history of corporate anti-union efforts. It represents how animation was used as a tool for political messaging long before the modern era of political cartoons. The film's existence demonstrates the sophisticated understanding that corporations like Ford had of media's power to shape public opinion and worker attitudes. It also reflects the broader cultural anxieties of the post-World War I period, when America was grappling with its role as a world power, the threat of communism, and massive social changes. The film is significant for understanding how visual media was employed to dehumanize political opponents and justify repression of labor movements. Its simple but powerful imagery contributed to the cultural narrative that painted union organizers and radicals as dangerous vermin threatening American values.

Making Of

The creation of this animated short by Ford Motor Company represents a fascinating intersection of early animation, corporate propaganda, and political messaging. The film was likely produced in-house by Ford's advertising department, which was innovative for its time. The animation techniques would have been rudimentary by modern standards, probably using cut-out animation or early cel methods. The decision to create such overt political propaganda demonstrates how seriously Ford took the threat of unionization and radical labor movements. The film's distribution was probably limited to Ford dealerships, company meetings, and possibly shown to employees as part of anti-union indoctrination. This was part of a broader pattern of Ford's efforts to control its workforce and prevent union organization, which would continue for decades.

Visual Style

The animation style of this 1919 short reflects the primitive techniques of early American animation. The film likely used cut-out animation or rudimentary cel animation, with simple character designs and limited movement. The visual composition would have been basic, focusing on clear, symbolic imagery rather than sophisticated animation techniques. The color scheme was probably limited or the film may have been in black and white, as color animation was still experimental at this time. The camera work would have been static, typical of early animation, with the focus on conveying the political message through clear, uncomplicated visuals. The artistic style prioritizes propaganda impact over aesthetic sophistication, using caricature and symbolism to make its political point unmistakably clear.

Innovations

While not technically innovative for its time, this film represents an early example of corporate use of animation for propaganda purposes. The production by Ford Motor Company, rather than a traditional animation studio, was unusual and demonstrated an early understanding of animation's potential as a persuasive medium. The film's use of symbolic imagery and clear visual messaging shows sophistication in propaganda techniques, if not in animation technology. The survival of any copies of this film is itself notable, given the fragility of early film stock and the limited distribution of such corporate materials. The film serves as a technical artifact of early 20th century animation methods and corporate communication strategies.

Music

This film was created during the silent era, so it would have had no synchronized soundtrack. When shown, it would have been accompanied by live music, typically a piano player in theaters or possibly a phonograph record in company settings. The musical accompaniment would have been chosen to match the film's patriotic and dramatic tone, likely including popular patriotic songs of the era. The lack of dialogue or sound effects meant the visual propaganda had to carry the entire message, which it does through clear symbolic imagery. The musical accompaniment would have been crucial in establishing the emotional tone and reinforcing the film's anti-radical, pro-American message.

Famous Quotes

No dialogue - silent film with visual propaganda message

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic scene where Uncle Sam strikes the I.W.W.-branded rat with a hammer, symbolizing the defeat of radical labor movements and the triumph of American values over perceived threats

Did You Know?

- This film was produced during the First Red Scare (1917-1920), a period of intense anti-communist hysteria in America

- The I.W.W. (Industrial Workers of the World) was a real radical labor union that faced severe government persecution during this era

- Ford Motor Company was notoriously anti-union and would later employ Harry Bennett to battle unionization efforts

- The film represents one of the earliest examples of corporate-sponsored political animation

- The rat symbolism was commonly used in propaganda to depict vermin that needed to be eliminated

- This cartoon predates Disney's establishment and represents early American animation techniques

- The film was likely shown in Ford dealerships or at company events rather than in commercial theaters

- Henry Ford himself was known for his anti-Semitic and anti-union views, which align with the film's message

- The bolsheviki reference connects domestic labor unrest to the Russian Revolution, a common fear tactic of the era

- Very few copies of this film are known to exist, making it an extremely rare piece of animation history

What Critics Said

As a propaganda piece rather than entertainment, this film was not subject to traditional critical review. Contemporary reception would have been divided along political lines - business owners and anti-communist Americans would have approved of its message, while labor organizers and civil libertarians would have condemned it as dangerous propaganda. The film was likely praised in business publications and conservative newspapers of the era. Modern film historians and animation scholars view it as an important example of early political animation and corporate propaganda, though its crude message and techniques are seen as products of their time. Animation historians note it as an example of how the medium was used for political purposes long before it became primarily associated with entertainment.

What Audiences Thought

The intended audience for this film was primarily Ford employees and business associates, rather than the general public. Among these groups, the reception would have been mixed - some would have accepted the anti-union message, while others might have resented the obvious propaganda. The film was likely shown in contexts where dissent was not welcomed, such as company meetings or dealer conventions. Working-class audiences, particularly those sympathetic to labor movements, would have recognized the film as hostile to their interests. The film's effectiveness as propaganda is difficult to measure, but it represents part of Ford's broader efforts to create a company culture resistant to unionization, an effort that was largely successful until the 1930s.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- World War I propaganda posters

- Political cartoons of the era

- Earlier animated shorts by pioneers like Winsor McCay

- Contemporary anti-radical literature

- Ford company internal communications

This Film Influenced

- Later corporate propaganda films

- Political animation of the 1920s-1930s

- Anti-communist cartoons of the Cold War era

- Modern political animation and advertisements

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Extremely rare - likely exists only in a few archival collections. May be partially lost or exist only in fragments. Preserved in specialized film archives focusing on animation or propaganda films.