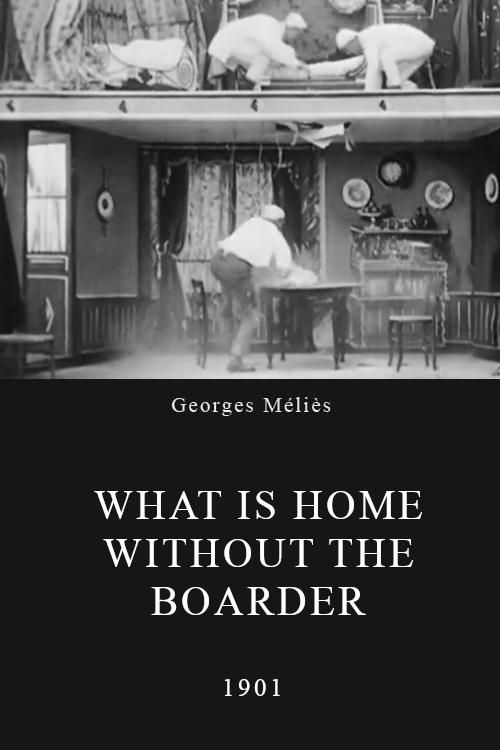

What Is Home Without the Boarder

Plot

In this early comedy short, three mischievous boarders create chaos in their boarding house by playing elaborate pranks on their long-suffering landlady. The troublemakers engage in increasingly disruptive behavior, turning the peaceful home into a scene of pandemonium with their antics. When a policeman is called to intervene and restore order, the boarders redirect their mischief toward him, leading to further comic complications. The film culminates in a series of slapstick gags and visual tricks characteristic of Méliès's style, ultimately leaving the landlady and law enforcement overwhelmed by the boarders' relentless pranks.

Director

About the Production

This film was created in Méliès's glass studio in Montreuil, which allowed for controlled lighting and the implementation of his signature special effects. The film was shot using the simple yet effective techniques Méliès had perfected, including substitution splices and multiple exposures. As with most of his films from this period, Méliès himself likely appeared in the film, possibly as one of the boarders or the policeman, given his tendency to act in his own productions.

Historical Background

This film was produced during the very dawn of cinema, only six years after the Lumière brothers' first public screening in 1895. In 1901, films were still primarily novelty attractions shown in fairgrounds, music halls, and traveling exhibitions rather than dedicated movie theaters. The film industry was in its infancy, with most productions being short, simple narratives or trick films. Méliès was one of the few filmmakers who had transitioned successfully from stage magic to cinema, and his Star Film Company was one of the most prolific production houses of the era. This period saw the development of basic film grammar and storytelling techniques that would become standard in cinema.

Why This Film Matters

As an early example of narrative comedy in cinema, this film helped establish the template for domestic comedy that would become a staple of film and television. It represents the transition from cinema as a mere spectacle of technical tricks to a medium for storytelling and character-based humor. The film's boarding house setting reflected common living arrangements in urban France at the turn of the century, making it relatable to contemporary audiences. Méliès's approach to comedy, combining physical gags with visual tricks, influenced countless later comedians and filmmakers. The film also demonstrates how early cinema began exploring social dynamics and power relationships through the lens of comedy, with the boarders subverting the authority of both their landlady and the police.

Making Of

The film was created in Méliès's innovative studio, which was essentially a glass-walled building that allowed maximum natural light for filming. Méliès, who began his career as a magician, brought theatrical sensibilities to his filmmaking, using painted backdrops and stage-like sets. The boarders and other characters were likely played by regular members of Méliès's troupe of actors who appeared in many of his films. The comedic timing and physical comedy would have been influenced by the popular French theatrical traditions of the time, particularly the comédie en vaudeville style. The film's special effects, while simpler than in Méliès's fantasy works, still demonstrate his mastery of cinematic tricks that would have amazed audiences of 1901.

Visual Style

The cinematography was typical of Méliès's work, featuring a single static camera position that captured the action as if from a theater audience's perspective. This approach reflected Méliès's theatrical background and allowed him complete control over the visual composition of his scenes. The lighting would have been natural light from the glass studio, supplemented by artificial lighting when necessary. The film was shot on 35mm film, which was the standard format of the era. Visual clarity and composition were priorities, as Méliès understood that audiences needed to clearly see the gags and trick effects for maximum impact.

Innovations

While not as technically ambitious as Méliès's fantasy films, this short still demonstrated several important cinematic techniques of the era. The use of substitution splices for comedic effect, where objects or characters would suddenly change or disappear, would have been employed to enhance the humor. The film likely utilized multiple exposures to create ghostly or magical effects even in this comedy context. The seamless editing and timing required for the physical comedy sequences represented an early mastery of cinematic rhythm. The film's existence itself was a technical achievement, representing the sophisticated studio production system Méliès had developed for consistent, high-quality output.

Music

As a silent film, it had no synchronized soundtrack. However, when shown in theaters, it would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small orchestra playing appropriate mood music. The musical accompaniment would have been improvised or selected from standard repertoire pieces that matched the on-screen action - lively, comedic music for the pranks and perhaps more dramatic music for the policeman's intervention. Some larger theaters might have employed sound effects artists to create noises in sync with the action, such as crashes or bangs during the chaotic scenes.

Did You Know?

- This film was released by Méliès's Star Film Company and was cataloged as number 322-323 in their productions list.

- The title plays on the common phrase 'What is home without a mother,' substituting 'boarder' for comic effect.

- Like many Méliès films, it was hand-colored in some releases, a labor-intensive process where each frame was colored by hand.

- The film was distributed internationally, including in the United States through Méliès's American distribution deals.

- This comedy represents Méliès's expansion beyond his famous fantasy and trick films into more straightforward comedic narratives.

- The policeman character was a common figure in early comedy films, representing authority figures who could be comically undermined.

- The film was created during Méliès's most productive period, when he was making dozens of films annually.

- Boarding house settings were popular in early comedy films as they allowed for multiple characters and chaotic situations in a confined space.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of films in 1901 was minimal, as film criticism as we know it today did not exist. Reviews, when they appeared, were typically brief notices in trade papers or general newspapers. Méliès's films were generally well-received by audiences and exhibitors for their entertainment value and technical innovation. Modern film historians and critics view this film as an important example of early cinematic comedy and Méliès's versatility beyond his famous fantasy films. It is often cited in scholarly works about the development of narrative comedy in cinema and Méliès's contribution to film language.

What Audiences Thought

Early audiences in 1901 would have been delighted by the film's combination of slapstick comedy and visual tricks. The sight gags and chaotic situations would have provided welcome entertainment in the context of a typical film program that might include newsreels, travelogues, and other short subjects. The boarding house setting would have been familiar and relatable to urban audiences of the time. The film's brevity (approximately 2 minutes) made it ideal for the short attention spans of early cinema audiences. Méliès's name was becoming well-known to regular filmgoers, and his productions were often advertised by exhibitors as special attractions.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- French vaudeville theater

- Stage magic traditions

- Commedia dell'arte

- Music hall entertainment

- Georges Méliès's own stage background

This Film Influenced

- Later domestic comedy shorts

- Keystone Cops films

- Chaplin's boarding house comedies

- Laurel and Hardy domestic situations

- Three Stooges shorts