E.A. Dupont

Director

About E.A. Dupont

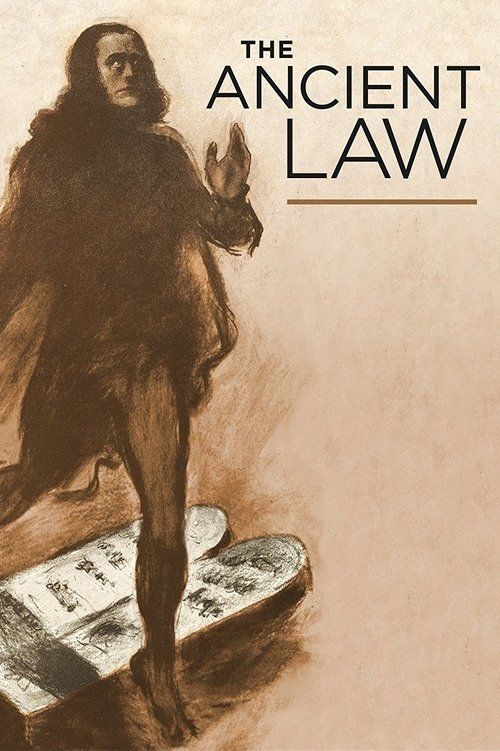

Ewald André Dupont was a pioneering German film director who emerged during the golden age of German Expressionist cinema in the 1920s. Born in Germany, Dupont began his career as a journalist and playwright before transitioning to filmmaking, where he quickly established himself as a master of visual storytelling. His 1923 film 'The Ancient Law' (Das alte Gesetz) showcased his ability to blend social commentary with cinematic innovation, telling the story of a Jewish scribe's son who dreams of becoming an actor. Dupont reached international acclaim with his 1925 masterpiece 'Varieté,' which featured groundbreaking camera techniques and psychological depth that influenced filmmakers worldwide. As the Nazi regime rose to power, Dupont, being Jewish, fled Germany in 1933 and continued his career in Britain, France, and eventually Hollywood, though he never quite recaptured the artistic success of his German period. His later years were marked by financial difficulties and declining health, but his contributions to early cinema, particularly his innovative use of camera movement and psychological storytelling, remain influential. Dupont's work represents a crucial bridge between German Expressionism and the emerging sound era, demonstrating how silent film techniques could convey complex emotional and narrative depth.

The Craft

Behind the Camera

E.A. Dupont was known for his innovative visual style and psychological depth, pioneering techniques that influenced generations of filmmakers. His directing approach emphasized dynamic camera movement, including tracking shots and unusual angles that created emotional intensity and visual spectacle. Dupont had a particular talent for exploring themes of alienation, desire, and social conflict through visual metaphor rather than dialogue. He was among the first directors to use subjective camera perspectives to immerse viewers in characters' psychological states, particularly evident in 'Varieté's' famous trapeze sequence. His work often featured complex lighting schemes influenced by German Expressionism, creating dramatic shadows and highlights that enhanced the emotional impact of his stories. Dupont's films frequently explored the lives of outsiders and artists, combining social commentary with personal drama in ways that felt both intimate and epic.

Milestones

- Directed 'The Ancient Law' (1923), a pioneering silent film about Jewish identity and artistic freedom

- Created 'Varieté' (1925), considered one of the masterpieces of German Expressionist cinema

- Pioneered innovative camera techniques including the famous roller coaster shot in 'Varieté'

- Fled Nazi Germany in 1933 due to his Jewish heritage

- Continued filmmaking career in Britain, France, and the United States

- Directed early sound films including 'Moulin Rouge' (1934) and 'Piccadilly Jim' (1936)

Best Known For

Must-See Films

Accolades

Won

- National Board of Review Award for Best Foreign Film for 'Varieté' (1925)

Nominated

- Academy Award nomination for Best Art Direction for 'The Love Parade' (1930)

Special Recognition

- Retrospective exhibitions at major film archives including the Museum of Modern Art

- Cited as influence by numerous directors including Alfred Hitchcock and Billy Wilder

Working Relationships

Worked Often With

Studios

Why They Matter

Impact on Culture

E.A. Dupont's impact on cinema extends far beyond his relatively small body of well-known works. His innovative camera techniques, particularly the subjective tracking shots in 'Varieté,' revolutionized visual storytelling and influenced countless directors who followed. Dupont was among the first directors to fully exploit cinema's potential for psychological depth, using visual rather than verbal means to explore complex emotional states. His films often dealt with themes of social alienation and the artist's struggle, resonating with audiences in the turbulent Weimar Republic and beyond. The success of 'The Ancient Law' helped establish the Jewish film as a significant genre in German cinema, addressing questions of identity and assimilation that remain relevant today. Dupont's work represents a crucial bridge between the theatrical influences of early cinema and the more psychologically sophisticated films of the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Lasting Legacy

E.A. Dupont's legacy as a pioneering director of silent cinema has undergone significant reappraisal in recent decades, with film historians recognizing his contributions to visual storytelling and psychological cinema. His masterpiece 'Varieté' is now regarded as one of the essential films of the German Expressionist movement, studied for its innovative camera work and emotional intensity. Dupont's influence can be traced through the work of directors like Alfred Hitchcock, who adopted similar subjective camera techniques, and Billy Wilder, who acknowledged Dupont's impact on his understanding of visual narrative. The preservation and restoration of Dupont's films by archives like the Museum of Modern Art and the Berlin Film Archive have ensured that new generations can appreciate his artistic vision. His career trajectory—from German Expressionist pioneer to Hollywood exile—also serves as a powerful reminder of the cultural losses caused by the Nazi regime's rise to power and the subsequent diaspora of Jewish artists.

Who They Inspired

Dupont's influence on cinema is most evident in his pioneering use of camera movement to convey psychological states, a technique that became standard in narrative filmmaking. His work in 'Varieté' particularly influenced the development of the subjective point-of-view shot, which directors like Hitchcock would later perfect in films like 'Vertigo.' The visual style Dupont developed, combining German Expressionist lighting with dynamic camera movement, influenced the look of film noir in the 1940s and 1950s. His approach to storytelling through visual rather than verbal means helped establish the language of cinema as distinct from theater. Dupont's success in international markets demonstrated that German films could compete globally, paving the way for other German directors to find work abroad. The themes of alienation and social conflict in his films resonated with later generations of filmmakers dealing with similar issues in their own cultural contexts.

Off Screen

Dupont's personal life was marked by both artistic success and personal tragedy. He married three times, with his first marriage to actress Lilian Harvey ending in divorce. His second marriage was to actress Mary Philbin, though this union also ended in divorce. Dupont's third marriage was to Lydia Lanchester, with whom he remained until his death. The rise of Nazism forced Dupont to flee his homeland in 1933, leaving behind his successful career and many personal connections. This exile deeply affected him personally and professionally, as he struggled to regain the artistic and commercial success he had enjoyed in Germany. In his later years, Dupont faced financial difficulties and health problems, including a stroke that left him partially paralyzed. He spent his final years in relative obscurity in Los Angeles, largely forgotten by the industry he had helped revolutionize.

Education

Studied literature and art history at universities in Dresden and Berlin before beginning his career as a journalist and playwright

Family

- Lilian Harvey (1926-1929)

- Mary Philbin (1930-1932)

- Lydia Lanchester (1933-1956)

Did You Know?

- Born on Christmas Day in 1891

- Originally worked as a journalist and theater critic before entering films

- His 1925 film 'Varieté' featured what is considered one of the earliest examples of a subjective camera sequence

- Fled Germany the same year Hitler came to power, leaving behind his successful career

- Worked in seven different countries during his exile from Germany

- His film 'The Ancient Law' was one of the first major films to deal with Jewish identity in cinema

- Dupont was one of the few German directors to successfully transition to Hollywood sound films

- He directed both Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich early in their careers

- His roller coaster sequence in 'Varieté' was filmed by attaching a camera to an actual roller coaster

- Dupont's films were banned by the Nazis and many were destroyed during World War II

- He died in relative poverty in Los Angeles, largely forgotten by the industry he had helped revolutionize

In Their Own Words

The camera must be the eye of the soul, not merely a recording device

In cinema, we paint with light and shadow, not with words

The greatest tragedy of the artist is that he sees what others cannot yet understand

Every film should be a window into another world, not merely a mirror of our own

The silent screen taught us that emotions need no translation

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was E.A. Dupont?

Ewald André Dupont was a pioneering German film director active during the 1920s and 1930s, best known for his contributions to German Expressionist cinema. He directed acclaimed films like 'The Ancient Law' (1923) and 'Varieté' (1925), and was forced to flee Nazi Germany due to his Jewish heritage, continuing his career in exile.

What films is E.A. Dupont best known for?

Dupont is most celebrated for 'The Ancient Law' (1923), a groundbreaking film about Jewish identity and artistic freedom, and 'Varieté' (1925), considered a masterpiece of German Expressionist cinema featuring innovative camera techniques. Other notable works include 'The Love Parade' (1929) and 'Moulin Rouge' (1934).

When was E.A. Dupont born and when did he die?

Ewald André Dupont was born on December 25, 1891, in Dresden, Germany, and died on December 12, 1956, in Los Angeles, California, at the age of 64. His final years were marked by financial difficulties and declining health.

What awards did E.A. Dupont win?

Dupont received the National Board of Review Award for Best Foreign Film for 'Varieté' in 1925 and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Art Direction for 'The Love Parade' in 1930. His work has been recognized posthumously through retrospectives at major film archives worldwide.

What was E.A. Dupont's directing style?

Dupont was known for his innovative visual style featuring dynamic camera movement, subjective perspectives, and Expressionist lighting. He pioneered techniques like tracking shots and unusual angles to create emotional intensity, often exploring themes of alienation and psychological depth through visual rather than verbal storytelling.

How did the rise of Nazism affect E.A. Dupont's career?

The Nazi regime's rise to power in 1933 forced Dupont, being Jewish, to flee Germany and abandon his successful career there. He continued working in Britain, France, and Hollywood but never achieved the same artistic or commercial success, and many of his German films were banned or destroyed by the Nazis.

What is E.A. Dupont's legacy in cinema history?

Dupont's legacy lies in his pioneering contributions to visual storytelling and psychological cinema, particularly his innovative camera techniques that influenced directors like Hitchcock. His work represents a crucial bridge between German Expressionism and international cinema, and his films continue to be studied for their artistic innovation and emotional depth.

Learn More

Films

1 film