A Lively Dream

Plot

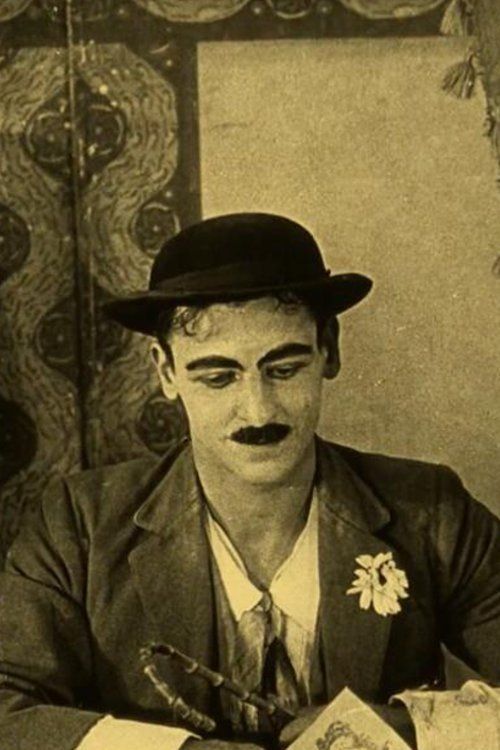

A young man becomes obsessed with imitating Charlie Chaplin's famous Tramp character, practicing the distinctive walk and mannerisms with great enthusiasm. His clumsy attempts at Chaplin-esque comedy lead him into increasingly troublesome situations as he tries to apply his imitation skills in real-life scenarios. The protagonist finds himself in a series of comedic misadventures, each more impossible than the last, as his eagerness to perform outweighs his actual talent. Throughout his escapades, he somehow manages to escape from the most precarious and ridiculous predicaments through sheer luck or circumstance. The film concludes with an ambiguous twist that leaves viewers questioning whether any of his fantastic adventures actually occurred, or if they were merely the product of an overactive imagination.

Director

About the Production

The film was produced during the golden age of Danish cinema when Nordisk Film was one of Europe's leading production companies. As a silent comedy, the film relied heavily on physical comedy and visual gags, typical of the Chaplin-influenced style popular during this period. The production would have used the standard film stock and camera equipment of the 1910s, with intertitles providing dialogue and narrative progression.

Historical Background

1917 was a pivotal year in world history and cinema. While World War I raged across Europe, Denmark maintained its neutrality, allowing its film industry to continue producing content for both domestic and international markets. This period represented the height of Danish cinema's global influence, with Danish films being exported worldwide. The Chaplin phenomenon had reached its peak, with the Tramp character becoming one of the first truly international film stars. Danish cinema was known for its technical innovation and artistic quality, particularly in genres like drama and comedy. The film industry was transitioning from short one-reelers to longer feature films, and comedy was evolving from simple slapstick to more sophisticated narrative forms. The war had disrupted film production in many European countries, but Denmark's neutral status gave its studios a competitive advantage in the international market.

Why This Film Matters

'A Lively Dream' represents an important example of how global film culture spread and adapted during the silent era. The Chaplin imitation phenomenon demonstrated the international reach of American cinema and how local filmmakers adapted foreign influences for domestic audiences. This film is part of a broader pattern of cultural exchange in early cinema, where characters, styles, and techniques crossed national boundaries with remarkable speed. The dream narrative structure also reflects early cinema's experimentation with surreal and psychological elements, prefiguring later developments in film language. As a Danish production engaging with an American cultural icon, the film illustrates the complex dynamics of cultural appropriation and adaptation in early 20th century entertainment. It also shows how comedy served as a universal language that could transcend cultural and linguistic barriers in the silent era.

Making Of

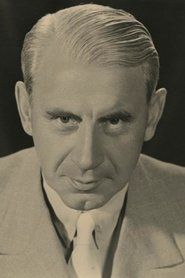

The making of 'A Lively Dream' reflects the rapid industrialization of cinema in Denmark during the 1910s. Director Lau Lauritzen Sr. was part of a generation of Danish filmmakers who helped establish the country's reputation for quality film production. The casting of Edmond Barenco as the Chaplin imitator suggests the actor may have specialized in physical comedy or had a particular talent for mimicry. The film's production would have taken place in Copenhagen's growing film studio facilities, where Nordisk Film had established state-of-the-art production spaces. The dream sequence elements would have required innovative camera techniques for the time, possibly including dissolves or multiple exposure effects to create the surreal atmosphere. As with many silent comedies of this era, the film would have relied on carefully choreographed physical stunts and timing, requiring extensive rehearsal and coordination between the actor and camera crew.

Visual Style

As a 1917 Danish comedy, the cinematography would have employed the relatively stationary camera techniques typical of the era, with occasional movement for tracking shots during chase sequences. The film would have used the standard 35mm film format with black and white imagery. Visual storytelling would have been paramount, with careful composition of frames to highlight physical comedy and facial expressions. The dream sequences would have utilized special effects techniques available at the time, such as multiple exposures, dissolves, or matte shots to create surreal imagery. The cinematographer would have worked closely with the director to ensure that the Chaplin-esque physical comedy was clearly visible and properly framed within the shot.

Innovations

While 'A Lively Dream' was not a groundbreaking technical achievement, it would have utilized the standard film technology of 1917 at a high level of craftsmanship. The dream sequences would have required the use of available special effects techniques such as double exposure or dissolves to create the surreal atmosphere. The physical comedy sequences would have demanded precise timing between the performers and camera work. The film would have been shot and edited using the continuity editing system that was becoming standardized during this period. The production would have benefited from Nordisk Film's reputation for technical quality and professional standards in Danish filmmaking.

Music

As a silent film, 'A Lively Dream' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The score would likely have been compiled from popular classical pieces and original compositions performed by a pianist or small orchestra in the cinema. The music would have been synchronized with the on-screen action, with upbeat, playful melodies accompanying the comedy scenes and more mysterious or dreamlike music for the fantasy sequences. The tempo and style of the music would have been crucial in establishing the comedic timing and emotional tone of each scene. Theatres might have used cue sheets provided by the distributor or created their own arrangements based on the film's content.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, dialogue was conveyed through intertitles and visual performance rather than spoken quotes

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where the protagonist first attempts his Chaplin imitation, likely featuring the iconic waddle walk and cane twirling; The climactic dream sequence where reality blurs into fantasy, possibly featuring impossible physical feats or surreal situations; The final scene that reveals the ambiguous nature of the protagonist's adventures, leaving the audience to question what was real and what was imagined

Did You Know?

- This film was part of a wave of Chaplin imitations that swept Europe during the 1910s, as Charlie Chaplin's Tramp character became an international phenomenon

- Director Lau Lauritzen Sr. was a pioneering figure in Danish cinema who would later establish his own production company

- The film's title 'A Lively Dream' (original Danish title likely 'En livlig Drøm') suggests the dream-like quality of the protagonist's adventures

- 1917 was during World War I, when Denmark remained neutral and its film industry continued to produce content for international markets

- The Chaplin imitation genre was particularly popular in Scandinavia, where local comedians adapted the Tramp character for regional audiences

- Nordisk Film, the likely production company, was founded in 1906 and is one of the world's oldest film companies still in operation

- Silent comedies from this era typically ran between 10-30 minutes, as feature-length films were still becoming standardized

- The film would have been accompanied by live musical accompaniment during its original theatrical run

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of 'A Lively Dream' are difficult to locate, as film criticism from Denmark's 1917 period was not as systematically preserved as in later decades. However, films of this type that engaged with popular Chaplin imitations were generally well-received by audiences seeking light entertainment during the difficult war years. Critics of the era typically focused on the technical execution of physical comedy and the lead actor's ability to capture the essence of Chaplin's performance style. The dream sequence elements would have been noted for their technical innovation. Modern film historians view such Chaplin imitations as important cultural artifacts that demonstrate the global influence of early Hollywood and the adaptability of silent comedy across different national cinemas.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1917 would have been familiar with Charlie Chaplin's work through the international distribution of his films, making the premise immediately accessible and entertaining. The combination of physical comedy and the dream narrative would have provided the escapist entertainment that wartime audiences craved. Danish audiences particularly appreciated comedy that balanced local sensibilities with international trends. The film's success would have depended largely on the lead actor's ability to create a sympathetic character while parodying Chaplin without being a mere copy. The ambiguous ending, questioning the reality of events, would have provided audiences with a sophisticated twist that elevated the film above simple slapstick.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Charlie Chaplin's Tramp character films

- Earlier Danish comedies

- American slapstick traditions

- European surrealist literature

- Music hall and vaudeville traditions

This Film Influenced

- Later Danish comedy films

- Other Chaplin imitation works

- Early European surreal comedies

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

As a 1917 Danish film, preservation status is uncertain. Many films from this era have been lost due to the fragile nature of early film stock and lack of systematic preservation efforts. However, if the film was part of Nordisk Film's catalog, there is a possibility that copies or elements may survive in the Danish Film Institute's archives or other European film archives. The film's survival would depend on whether it was considered significant enough for preservation during the mid-20th century when many early films were discarded or deteriorated.