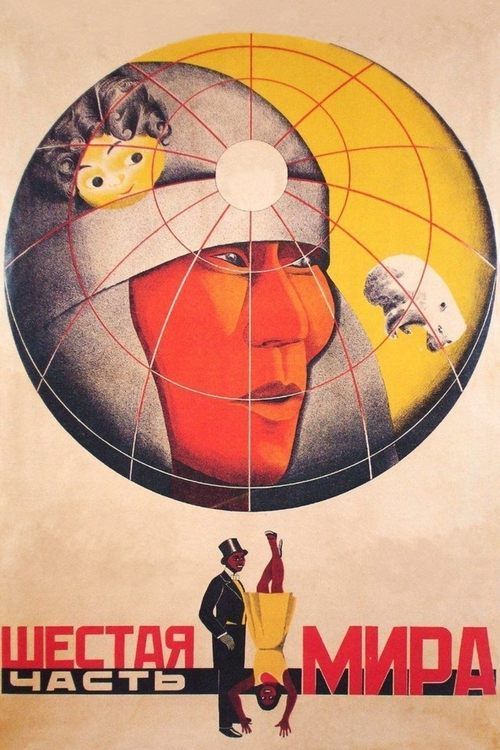

A Sixth Part of the World

"A journey through the Soviet Union showing the wealth of the land and the unity of its peoples"

Plot

Dziga Vertov's 'A Sixth Part of the World' is a groundbreaking documentary that traverses the vast expanse of the Soviet Union, showcasing the incredible diversity of its peoples, landscapes, and economic activities. The film follows a journey through remote regions from the Arctic north to the Asian steppes, documenting indigenous peoples like the Samoyeds, Buryats, and various Turkic tribes alongside modern industrial workers in cities. Vertov captures the contrast between traditional ways of life and the emerging socialist society, showing how different ethnic groups contribute to the collective Soviet economy through hunting, farming, mining, and manufacturing. The documentary serves as both an ethnographic record and a propaganda piece, emphasizing the wealth of Soviet resources and the need for all peoples to unite in building socialism. Through innovative editing techniques and striking visual compositions, Vertov creates a powerful argument for Soviet unity and the transformative potential of collective labor under communism.

Director

About the Production

Filmed over approximately one year (1925-1926) using multiple camera teams dispatched to different regions of the USSR. Vertov and his brother Mikhail Kaufman pioneered mobile camera techniques, often mounting cameras on trains, boats, and even moving vehicles to capture dynamic footage. The production faced extreme challenges including harsh weather conditions in Arctic regions, difficult terrain in mountainous areas, and communication barriers with remote ethnic groups. Vertov employed his famous 'kino-eye' theory, believing the camera could capture reality more truthfully than the human eye, leading to innovative camera angles and rapid editing techniques that were revolutionary for the time.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the New Economic Policy (NEP) period in the Soviet Union, a time of relative cultural openness preceding Stalin's consolidation of power. 1926 was a pivotal year for Soviet cinema, with the government recognizing film as a powerful tool for education and propaganda. The Soviet Union was still in its early stages, having been formed only four years earlier, and there was an urgent need to create a unified Soviet identity among dozens of distinct ethnic groups spread across eleven time zones. Vertov's film emerged alongside other Soviet avant-garde masterpieces like Eisenstein's 'Battleship Potemkin' (1925) and Pudovkin's 'Mother' (1926), representing a golden age of Soviet cinematic innovation. The film also reflected the Soviet emphasis on industrialization and modernization, showcasing both traditional ways of life and the new socialist society being built across the nation.

Why This Film Matters

'A Sixth Part of the World' represents a landmark in documentary filmmaking, establishing techniques and approaches that would influence the genre for decades. Vertov's innovative use of montage, mobile camerawork, and rhythmic editing created a new cinematic language that went beyond simple documentation to create what he called 'cine-poetry.' The film's emphasis on showing the Soviet Union's diversity while promoting unity helped establish the visual vocabulary of Soviet multiculturalism. Its influence can be seen in later documentary traditions, from the British Documentary Movement of the 1930s to the cinéma vérité of the 1960s. The film also demonstrated how documentary could serve both artistic and political purposes without sacrificing aesthetic innovation. Vertov's approach to capturing 'life caught unawares' would become a fundamental principle of documentary ethics and practice, while his technical innovations expanded the possibilities of what cinema could show and how it could show it.

Making Of

The production of 'A Sixth Part of the World' was an ambitious undertaking that required extensive planning and coordination across the vast Soviet territory. Vertov organized multiple camera teams that simultaneously filmed in different regions, creating a logistical challenge that required careful synchronization. The filmmakers often had to travel by dog sled, reindeer, camel, or primitive vehicles to reach remote locations, sometimes spending weeks in harsh conditions. Vertov's revolutionary approach included hiding cameras to capture authentic reactions, using mirrors for unusual angles, and developing rapid editing techniques that would later influence countless filmmakers. The post-production process was equally innovative, with Vertov and Svilova spending months in the editing room, experimenting with montage techniques to create rhythmic patterns and intellectual connections between disparate images. The film's creation coincided with Vertov's development of his 'kino-eye' theory, which argued that cinema could reveal truths invisible to the naked eye through mechanical objectivity and creative editing.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'A Sixth Part of the World' was revolutionary for its time, featuring unprecedented camera mobility and innovative angles. Mikhail Kaufman and his team employed numerous technical innovations including handheld cameras, concealed cameras for candid shots, and cameras mounted on moving vehicles, trains, and boats to create dynamic tracking shots. The film features extreme close-ups, low angles, and aerial perspectives that were technically challenging in 1926. Vertov's 'kino-eye' approach led to experiments with split screens, multiple exposures, and superimpositions to create intellectual and visual connections between different images. The cinematography also demonstrates remarkable technical skill in capturing diverse environments, from the blinding snow of Arctic regions to the intense heat of Central Asian deserts. The film's visual style emphasizes geometric patterns and rhythmic repetitions, creating a visual symphony that matches Vertov's conception of cinema as music made of images.

Innovations

The film pioneered numerous technical innovations that would become standard in documentary filmmaking. Vertov and his team developed portable camera equipment that could be operated in extreme weather conditions, allowing them to capture footage in locations previously considered inaccessible to film crews. They experimented with underwater photography, aerial shots from primitive aircraft, and time-lapse photography to show natural processes. The film's editing techniques were particularly groundbreaking, featuring rapid montage, rhythmic cutting, and intellectual montage that created conceptual connections between disparate images. Vertov also developed techniques for synchronizing multiple cameras and for creating seamless transitions between shots filmed in different locations and at different times. The film's preservation of diverse ethnic performances and traditional practices represents an invaluable ethnographic achievement, capturing cultural practices that have since disappeared or been transformed.

Music

As a silent film, 'A Sixth Part of the World' was originally accompanied by live musical performances, typically featuring a specially composed score by Vladimir Deshevov that incorporated elements from various Soviet folk traditions alongside modernist orchestral techniques. The musical score was designed to complement the film's rhythmic editing and to musically represent the diversity of Soviet peoples shown on screen. Different theaters employed various approaches to musical accompaniment, from full orchestras to smaller ensembles, and some screenings included folk musicians from the regions depicted in the film. Modern restorations have been accompanied by newly commissioned scores from contemporary composers who attempt to capture the spirit of Vertov's original vision while using modern musical resources. The film's rhythmic structure and editing patterns have often been compared to musical compositions, with some scholars suggesting that Vertov conceived of his editing in musical terms.

Famous Quotes

I am kino-eye, I am a mechanical eye. I, a machine, show you the world as only I can see it.

From the citizen of the new economic society to the citizen of the future socialist society.

The sixth part of the world - a land of unprecedented wealth and unlimited possibilities.

We are building a new world, and cinema is our instrument of construction.

In the unity of all peoples lies the strength of the Soviet land.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing a map of the Soviet Union dissolving into actual footage of its diverse landscapes and peoples

- The dramatic montage of reindeer herders in the Arctic transitioning to factory workers in industrial centers

- The sequence showing traditional crafts and industries alongside modern machinery, emphasizing continuity and progress

- The powerful montage of different ethnic groups performing their traditional dances and ceremonies

- The climactic sequence showing various peoples looking directly into the camera, creating a sense of unity and shared purpose

Did You Know?

- The title 'A Sixth Part of the World' refers to the Soviet Union constituting approximately one-sixth of the Earth's land surface

- Vertov's brother Mikhail Kaufman was the primary cinematographer, while their other brother Boris Kaufman later became a renowned cinematographer in France and Hollywood

- The film contains footage from over 20 different ethnic groups and regions across the Soviet Union

- Vertov considered this film a 'cinema poem' rather than a straightforward documentary

- The intertitles were written by Vertov's wife and collaborator, Yelizaveta Svilova

- The film was shot using approximately 30,000 meters of film stock, though only about 2,000 meters made it into the final cut

- Some scenes were staged or re-enacted for the camera, a common practice in early documentary filmmaking

- The film includes footage of the famous 'icebreaker' ships that were symbols of Soviet technological progress

- Vertov and his team developed portable camera equipment specifically for this expedition-style filming

- The original musical score was composed by Vladimir Deshevov and performed live during screenings

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its innovative techniques and patriotic message, with prominent critic Viktor Shklovsky hailing it as a triumph of the 'kino-eye' theory. Western critics who managed to see the film were impressed by its technical virtuosity, though some questioned its propagandistic elements. Over time, the film has been reassessed as a masterpiece of early documentary cinema, with modern critics celebrating Vertov's formal innovations and his complex approach to representing cultural diversity. Film scholar Jay Leyda described it as 'perhaps the most successful of all Vertov's attempts to create a symphony of the Soviet world.' The film is now studied in film schools worldwide as a prime example of avant-garde documentary techniques and early Soviet cinema at its most innovative. Recent scholarship has also examined the film's complex relationship to ethnography and its role in constructing Soviet identity.

What Audiences Thought

The film was widely screened throughout the Soviet Union as part of the state's educational and propaganda programs, reaching both urban and rural audiences through mobile cinema units. Contemporary reports suggest that Soviet audiences were particularly impressed by the footage of remote regions and peoples they had never seen before, as the film served to introduce citizens to the vastness and diversity of their country. The film's rhythmic editing and dynamic visuals made it popular even with audiences who might have been resistant to more overt propaganda. International audiences had limited access to the film due to political barriers, but where it was shown, particularly in left-wing circles in Europe and America, it was celebrated for its technical innovation. Modern audiences viewing the restored version often express astonishment at the film's contemporary feel and its sophisticated editing techniques that seem decades ahead of their time.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were given to Soviet films internationally in 1926 due to political isolation

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Vertov's earlier newsreel work for Kino-Nedelya

- The cinematic theories of Lev Kuleshov regarding montage

- Futurist art movements and their celebration of technology

- Soviet constructivist art and design principles

- Traditional ethnographic photography and documentation

- American city symphony films like 'Manhatta' (1921)

- The travelogue genre popular in early cinema

This Film Influenced

- Vertov's own 'Man with a Movie Camera' (1929)

- Joris Ivens' 'Rain' (1929)

- Luis Buñuel's 'Las Hurdes: Tierra Sin Pan' (1933)

- Leni Riefenstahl's 'Triumph of the Will' (1935)

- The British Documentary Movement films of the 1930s

- Cinema vérité films of the 1960s

- Modern documentary series like 'Planet Earth'

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved and restored by various archives including the Gosfilmofond in Moscow and the British Film Institute. A restored version was released in the 1990s with improved image quality and new musical accompaniment. The original nitrate negatives have suffered some deterioration over time, but enough material survives to present a complete version of the film. Multiple restoration projects have worked to preserve both the visual elements and as much of the original intertitle text as possible. The film is now considered part of the world's documentary heritage and has been included in several important film preservation initiatives.