Dziga Vertov

Director

About Dziga Vertov

Dziga Vertov, born Denis Arkadyevich Kaufman, was a revolutionary Soviet documentary filmmaker and film theorist who fundamentally transformed cinematic language during the 1920s. After studying music and medicine in his youth, he turned to journalism and filmmaking following the 1917 Russian Revolution, adopting the name 'Dziga' (meaning 'spinning top' in Ukrainian) to reflect his dynamic energy. He developed the groundbreaking 'Kino-Eye' theory, which posited that the camera could capture reality more authentically than human perception, leading to his experimental documentary series 'Kino-Pravda' (Film Truth) from 1922-1925. His masterpiece 'Man with a Movie Camera' (1929) remains one of the most innovative films in cinema history, employing rapid editing, split screens, multiple exposures, and self-reflexive techniques to create a symphony of urban life. Despite facing political pressure during the Stalinist era for his avant-garde approach, Vertov continued making films until his death, though his later works were more conventional to appease Soviet authorities. His theoretical writings and experimental techniques influenced generations of filmmakers, from Jean-Luc Godard to contemporary documentarians, cementing his legacy as one of cinema's true pioneers.

The Craft

Behind the Camera

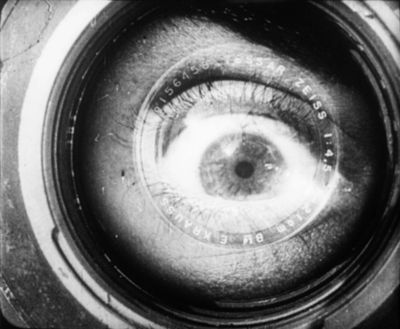

Vertov's directing style was radically experimental and avant-garde, rejecting traditional narrative storytelling in favor of what he called 'life caught unawares.' He employed rapid montage, jump cuts, multiple exposures, split screens, Dutch angles, and self-reflexive techniques to create a new cinematic language. His approach emphasized the mechanical eye of the camera over human perception, using editing to construct meaning from seemingly unrelated images. Vertov often included the filmmaking process within his films, showing cameras, editing equipment, and even himself as director, breaking the fourth wall decades before it became fashionable. His rhythmic editing patterns created visual symphonies that paralleled musical structures, particularly evident in his urban documentaries that captured the modernization of Soviet society.

Milestones

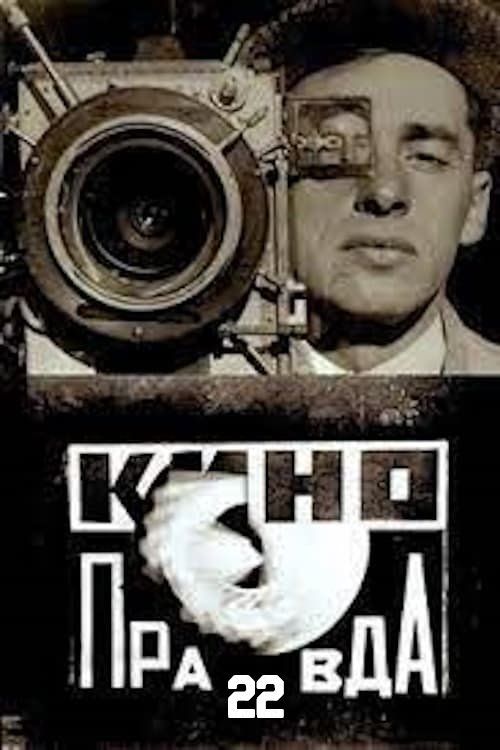

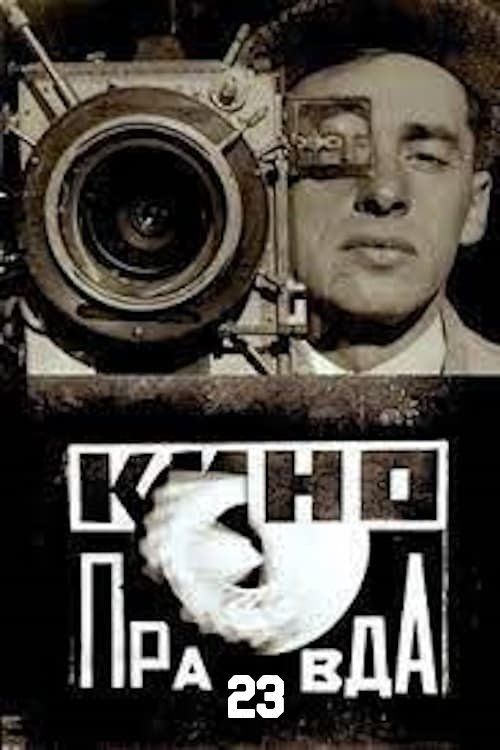

- Created the revolutionary 'Kino-Pravda' newsreel series (1922-1925)

- Developed and implemented the 'Kino-Eye' theory of documentary filmmaking

- Directed the groundbreaking masterpiece 'Man with a Movie Camera' (1929)

- Pioneered techniques including rapid editing, split screens, and multiple exposures

- Established documentary film as a legitimate artistic medium

- Influenced generations of filmmakers with his theoretical writings

Best Known For

Must-See Films

Accolades

Won

- Stalin Prize (1946) for 'In the Mountains of Ala-Tau'

- Order of the Red Banner of Labour (1935)

Special Recognition

- Voted among the top 10 directors of all time in the 2002 Sight & Sound poll

- 'Man with a Movie Camera' ranked 8th greatest film ever made in the 2012 Sight & Sound critics' poll

- Preserved in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress

- Multiple films preserved by the Criterion Collection for their historical significance

Working Relationships

Worked Often With

Studios

Why They Matter

Impact on Culture

Dziga Vertov revolutionized documentary filmmaking and cinematic language through his radical experiments with form and technique. His 'Kino-Eye' theory challenged traditional notions of realism by arguing that the camera could reveal truths invisible to the naked eye, fundamentally altering how filmmakers approached documentary. Vertov's innovative editing techniques, including rapid montage and visual rhythm, influenced the development of music videos, commercials, and contemporary documentary practices. His work demonstrated that documentary could be as artistically ambitious as fiction film, elevating the genre's cultural status. Vertov's emphasis on the mechanical nature of cinema and his self-reflexive style presided over postmodern film theory by decades. His films captured the Soviet Union's ambitious modernization projects while simultaneously creating a new visual language for representing urban life and industrial progress.

Lasting Legacy

Dziga Vertov's legacy endures as one of cinema's most innovative theorists and practitioners, whose influence spans across decades and continents. 'Man with a Movie Camera' continues to be studied in film schools worldwide as a masterpiece of cinematic technique and remains one of the most influential experimental films ever made. His theoretical writings on the 'Kino-Eye' concept contributed significantly to film theory, influencing documentary ethics and aesthetics throughout the 20th century. Vertov's techniques have been absorbed into mainstream cinema language, with his editing innovations visible in everything from action sequences to contemporary documentaries. The preservation and restoration of his films have introduced new generations to his revolutionary vision, while his emphasis on capturing 'life caught unawares' continues to influence documentary ethics and approaches. Vertov's work represents a unique intersection of artistic innovation and political ideology, demonstrating how avant-garde art can serve revolutionary purposes while pushing artistic boundaries.

Who They Inspired

Vertov's influence permeates modern cinema, particularly in documentary and experimental filmmaking. The French New Wave directors, especially Jean-Luc Godard, explicitly cited Vertov as a major influence, adopting his self-reflexive techniques and rejection of traditional narrative. Contemporary documentarians like Errol Morris, Werner Herzog, and Harmony Korine have drawn from Vertov's approach to capturing reality. His editing techniques anticipated music video aesthetics by decades, while his use of multiple screens and split screens foreshadowed digital media practices. Vertov's theoretical work influenced film theorists from André Bazin to Jean-Louis Baudry, contributing to debates about realism, apparatus theory, and the nature of cinematic representation. His emphasis on the camera as truth-telling device influenced cinéma vérité and direct cinema movements in the 1960s. Even modern advertising and corporate videos borrow from Vertov's rhythmic editing and celebration of industrial processes.

Off Screen

Vertov was married to Elizaveta Svilova, who served as his editor and crucial collaborator on most of his major works. Their partnership was both personal and professional, with Svilova's editing skills essential to realizing Vertov's complex vision. He came from a family of filmmakers - his brother Mikhail Kaufman was his primary cinematographer early in his career, while another brother, Boris Kaufman, later won an Academy Award for cinematography in Hollywood. Vertov was known for his intense dedication to his craft and his ideological commitment to the Soviet revolution, though his avant-garde approach often put him at odds with Soviet cultural authorities. Despite his Jewish heritage, he maintained his position in the Soviet film industry throughout his career, though he faced increasing pressure to conform to socialist realism in his later years.

Education

Studied music at the Białystok Conservatory, attended psychoneurological institute in Petrograd, studied medicine briefly before turning to journalism and film

Family

- Elizaveta Svilova (married 1924-1954)

Did You Know?

- His pseudonym 'Dziga' means 'spinning top' in Ukrainian, reflecting his energetic personality

- His brother Boris Kaufman won an Academy Award for 'On the Waterfront' (1954)

- He initially wanted to be a composer and studied at the Białystok Conservatory

- 'Man with a Movie Camera' had no script, no actors, and no intertitles when originally released

- He was expelled from the Soviet film studio in 1929 for being 'too formalist'

- His film 'Enthusiasm' (1931) was the first Soviet film to feature a synchronized soundtrack

- Vertov's wife Elizaveta Svilova edited most of his major films and was crucial to his creative process

- His brother Mikhail Kaufman, who shot 'Man with a Movie Camera', later made his own documentary criticizing Vertov

- Vertov's films were banned in the Soviet Union for years but celebrated internationally

- The British rock band 'Public Image Ltd' named their 1979 album 'Metal Box' after Vertov's editing techniques

In Their Own Words

I am kino-eye, I am a mechanical eye. I, a machine, show you the world as only I can see it.

The camera's eye is more perfect than the human eye. It can see more than the human eye.

We cannot improve the reality that we film, but we can improve it through editing.

Film-drama is the opium of the people... down with Bourgeois fairy-tale scenarios... long live life as it is!

The goal of the kino-eye is to create the truly objective film, a film written directly on celluloid without the interference of human subjectivity.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Dziga Vertov?

Dziga Vertov was a pioneering Soviet documentary filmmaker and film theorist who revolutionized cinematic language in the 1920s. Born Denis Kaufman, he developed the 'Kino-Eye' theory and created groundbreaking films like 'Man with a Movie Camera' that introduced innovative techniques including rapid editing, split screens, and self-reflexivity. His work fundamentally transformed documentary filmmaking and influenced generations of filmmakers worldwide.

What films is Dziga Vertov best known for?

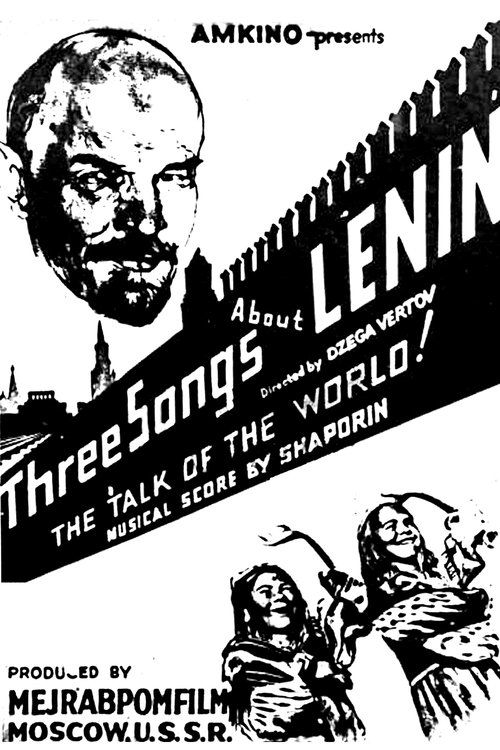

Vertov is most famous for 'Man with a Movie Camera' (1929), considered one of the greatest and most innovative films ever made. Other major works include his 'Kino-Pravda' newsreel series (1922-1925), 'Kino-Eye' (1924), 'A Sixth Part of the World' (1926), 'The Eleventh Year' (1928), 'Enthusiasm' (1931), and 'Three Songs About Lenin' (1934). These films showcase his revolutionary approach to documentary filmmaking and editing techniques.

When was Dziga Vertov born and when did he die?

Dziga Vertov was born Denis Arkadyevich Kaufman on January 2, 1896, in Białystok, which was then part of the Russian Empire (now Poland). He died on February 12, 1954, in Moscow, Soviet Union, at the age of 58. Throughout his life, he remained a significant figure in Soviet cinema despite facing political pressure for his avant-garde approach.

What was the 'Kino-Eye' theory?

The 'Kino-Eye' theory was Vertov's revolutionary concept that the camera could capture reality more authentically and truthfully than human perception. He believed that through editing and mechanical recording, cinema could reveal truths invisible to the naked eye, creating a new form of visual truth. This theory rejected traditional narrative filmmaking in favor of capturing 'life caught unawares' and using editing to construct meaning from raw footage.

How did Dziga Vertov influence modern cinema?

Vertov's innovations in editing techniques, including rapid montage, jump cuts, and split screens, have become standard tools in modern filmmaking. His self-reflexive style influenced the French New Wave directors, particularly Jean-Luc Godard. His work anticipated music video aesthetics, documentary vérité, and even digital media practices. Contemporary filmmakers continue to study his techniques and theoretical contributions to documentary ethics and cinematic language.

What was Vertov's relationship with Soviet authorities?

Vertov's relationship with Soviet authorities was complex and often contentious. While he was a committed revolutionary who supported the Soviet cause, his avant-garde artistic approach frequently clashed with official cultural policies, particularly during the Stalinist era when socialist realism became mandatory. He was expelled from the Soviet film studio in 1929 for being 'too formalist' and faced increasing pressure to conform his style to state-approved aesthetics throughout his career.

Did Dziga Vertov have any family in filmmaking?

Yes, Vertov came from a family of notable filmmakers. His brother Mikhail Kaufman was his primary cinematographer on early projects, while another brother, Boris Kaufman, moved to Hollywood and won an Academy Award for cinematography on 'On the Waterfront' (1954). Vertov was married to Elizaveta Svilova, who served as his editor and crucial collaborator on most of his major films, making their partnership both personal and professional.

Learn More

Films

14 films

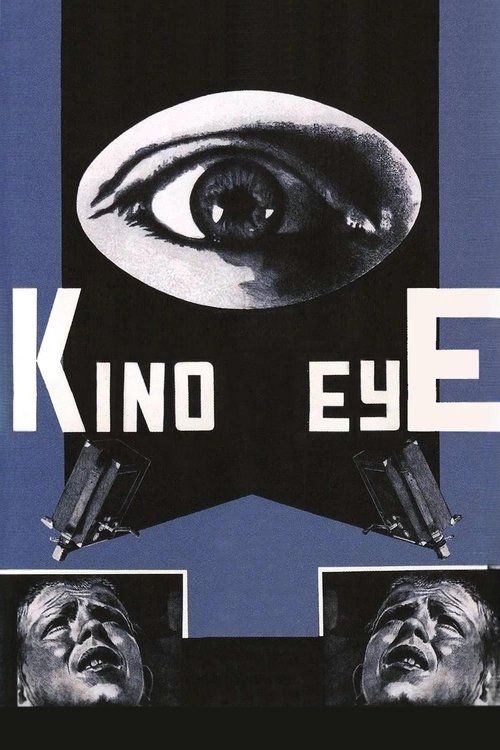

Kino Eye

1924

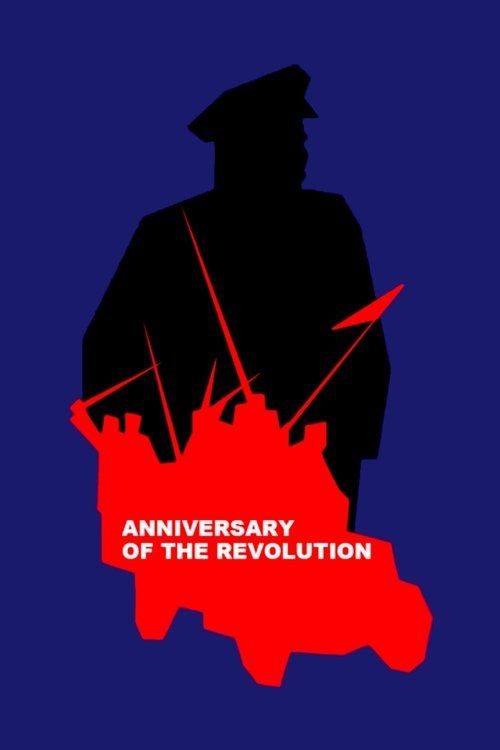

Anniversary of the Revolution

1918

Man with a Movie Camera

1929

Three Songs About Lenin

1934

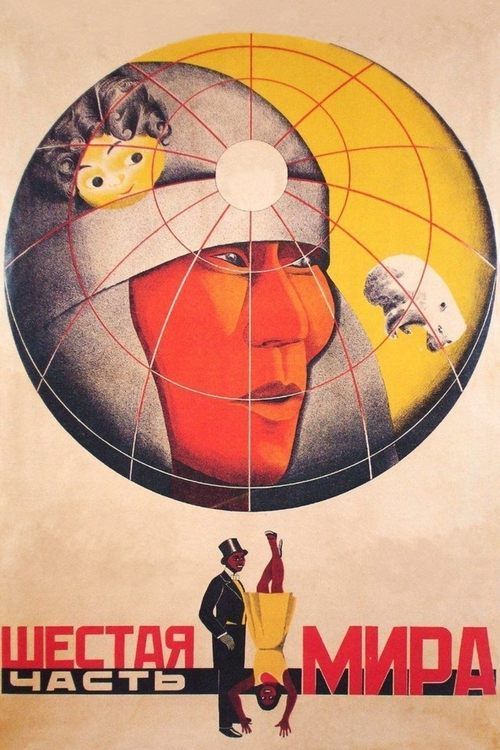

A Sixth Part of the World

1926

Enthusiasm. Symphony of Donbas

1930

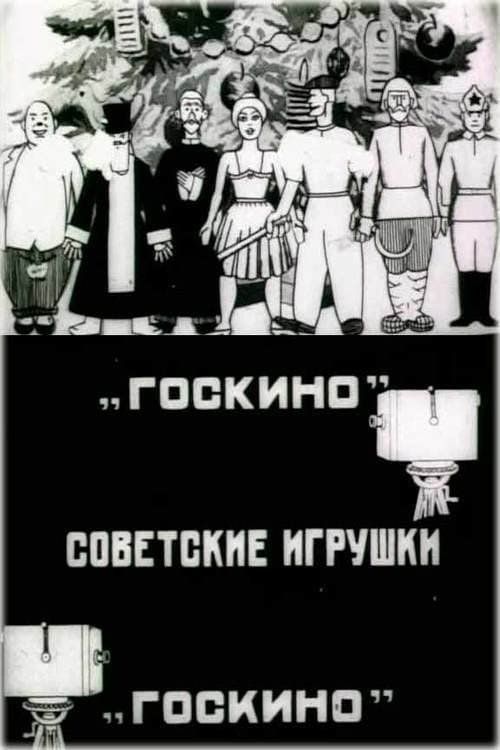

Soviet Toys

1924

Kino-Pravda No. 22: Lenin Is Alive in the Heart of the Peasant. A Film Story

1925

Kino-Pravda No. 23: Radio Pravda

1925

Kino-Pravda No. 15

1923

Kino-Pravda No. 17

1923

Kino-Pravda No. 18: A Movie-Camera Race Over 299 Metres and 14 Minutes and 50 Seconds in the Direction of Soviet Reality

1924

Kino-Pravda No. 19: A Movie-Camera Race Moscow – Arctic Ocean

1924