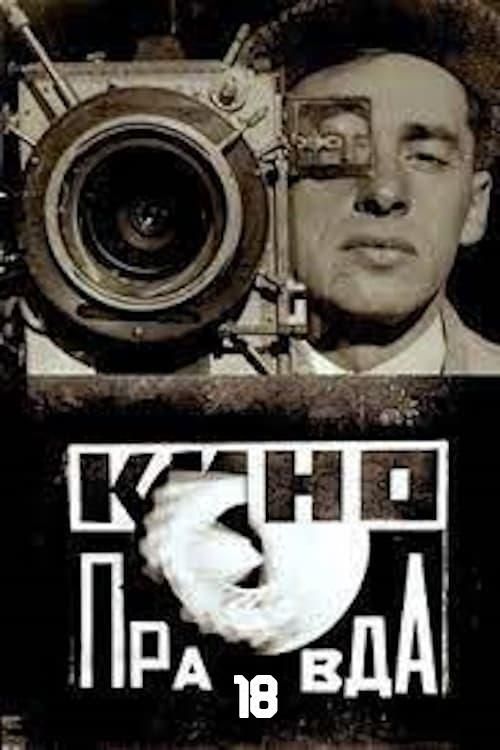

Kino-Pravda No. 18: A Movie-Camera Race Over 299 Metres and 14 Minutes and 50 Seconds in the Direction of Soviet Reality

"A Movie-Camera Race Over 299 Metres and 14 Minutes and 50 Seconds in the Direction of Soviet Reality"

Plot

Kino-Pravda No. 18 is a groundbreaking Soviet newsreel that combines multiple documentary segments into a cohesive vision of Soviet reality. The film begins with an ascent up the Eiffel Tower in Paris, contrasting Western architecture with Soviet progress, before transitioning to Moscow cityscapes and an auto race between Petrograd and Moscow showcasing Soviet technological advancement. The documentary captures intimate moments of everyday Soviet life, following a peasant from Yaroslavl on his first visit to Moscow, and culminates in the ceremonial introduction of a newborn into a workers' collective, symbolizing the birth of the new Soviet man. Through rapid editing, multiple exposures, and innovative camera techniques, Vertov creates a dynamic portrait of a society in transformation.

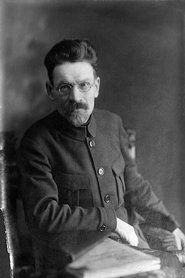

Director

Cast

About the Production

Filmed as part of Dziga Vertov's Kino-Pravda series, this entry was notable for its international scope, including rare footage from Paris. The production employed Vertov's brother Mikhail Kaufman as cinematographer, utilizing handheld cameras and innovative mounting techniques. The film was shot on 35mm film and processed at state facilities. Vertov experimented with multiple exposures and rapid montage techniques to create what he called 'film truth' or 'kino-pravda'.

Historical Background

Kino-Pravda No. 18 was produced during Lenin's New Economic Policy (NEP) period, a time of relative cultural freedom in the Soviet Union before Stalin's consolidation of power. 1924 was the year of Lenin's death, creating a period of uncertainty and transition in Soviet leadership. The film reflects the Soviet state's emphasis on modernization, industrialization, and the creation of a new socialist society. The auto race between Petrograd and Moscow symbolized Soviet technological progress, while the focus on everyday workers and peasants aligned with communist ideology. The inclusion of Paris footage suggests an awareness of Western developments and a desire to position the Soviet Union as a modern, forward-looking nation on the world stage. This was also the period when Soviet avant-garde cinema was flourishing, with filmmakers like Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Vertov experimenting with new cinematic languages.

Why This Film Matters

Kino-Pravda No. 18 represents a crucial moment in the development of documentary cinema and Soviet avant-garde film. Vertov's approach to filmmaking, which he called 'cine-eye' theory, argued that the camera could capture truth more objectively than the human eye, free from psychological bias. This film, along with others in the Kino-Pravda series, established many techniques that would become standard in documentary filmmaking, including handheld camera work, location shooting, and rapid montage. The series influenced generations of documentary filmmakers, from the British Documentary Movement of the 1930s to the cinéma vérité movement of the 1960s. Vertov's emphasis on the camera as a mechanical eye and his rejection of traditional narrative structures prefigured later debates about documentary truth and representation. The film also serves as a valuable historical document of early Soviet society, capturing everyday life during a transformative period in Russian history.

Making Of

The production of Kino-Pravda No. 18 exemplified Vertov's radical approach to documentary filmmaking. Working with a small crew including his brother Mikhail Kaufman as cinematographer and wife Elizaveta Svilova as editor, Vertov rejected traditional narrative structures in favor of what he called 'intervals' - the rhythmic relationships between shots. The team developed innovative camera mounting techniques, including attaching cameras to automobiles, bicycles, and even moving trains to capture dynamic footage. The Paris sequence was particularly challenging to obtain, requiring either special permission from Soviet authorities or clandestine filming. Vertov insisted on capturing real events without staging, though he was not above manipulating footage through editing to create his desired ideological message. The rapid cutting style, sometimes featuring dozens of shots per minute, was revolutionary for its time and required Svilova to develop new editing techniques.

Visual Style

The cinematography in Kino-Pravda No. 18 was revolutionary for its time, featuring handheld camera work, unusual angles, and dynamic movement. Mikhail Kaufman, Vertov's brother and primary cinematographer, employed innovative techniques including mounting cameras on moving vehicles, using split screens, and experimenting with multiple exposures. The film features rapid cutting between different locations and subjects, creating a rhythmic montage that Vertov believed could reveal deeper truths about Soviet reality. The Paris sequence includes dramatic upward shots of the Eiffel Tower, while the Moscow scenes utilize street-level perspectives that put viewers in the midst of everyday Soviet life. The auto race sequence uses tracking shots and multiple camera positions to create excitement and convey the speed of modern progress.

Innovations

Kino-Pravda No. 18 pioneered several technical innovations in documentary filmmaking. Vertov and his team developed methods for mounting cameras on moving vehicles, creating smooth tracking shots that were technically challenging in the 1920s. The film's rapid montage editing, sometimes cutting between dozens of shots per minute, required precise timing and innovative editing techniques developed by Elizaveta Svilova. The use of multiple exposures and superimposition created visual effects that emphasized the film's thematic concerns. The international scope of the production, combining footage from Paris with Soviet locations, demonstrated new possibilities for documentary coverage. The film also experimented with different film speeds and reverse motion to create visual interest and emphasize certain moments.

Music

As a silent film from 1924, Kino-Pravda No. 18 had no synchronized soundtrack. In Soviet theaters, it would have been accompanied by live musical performance, typically piano or small ensemble, with music selected or improvised to match the on-screen action. Some screenings might have included a narrator explaining the scenes, particularly for educational purposes. The rhythm and pacing of the editing suggest that Vertov conceived of the film with musical considerations in mind, using visual rhythm as a substitute for musical rhythm. Modern restorations sometimes add contemporary scores, but purists argue that the film should be experienced as originally intended, either in silence or with period-appropriate live accompaniment.

Famous Quotes

'I am the cine-eye, I am a mechanical eye. I, a machine, show you the world as only I can see it.' - Dziga Vertov's manifesto

'The camera's eye is more perfect than the human eye.' - Vertov's theoretical position

'Film truth: the capture of life unawares.' - Vertov's definition of Kino-Pravda

'We cannot improve the making of eyes, but we can perfect the camera.' - Vertov on technological progress

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic ascent up the Eiffel Tower, contrasting Western architecture with Soviet progress

- The high-speed auto race sequence between Petrograd and Moscow, showcasing Soviet technological advancement

- The intimate scenes of a peasant from Yaroslavl experiencing Moscow for the first time

- The ceremonial introduction of a newborn into a workers' collective, symbolizing the birth of the new Soviet person

- The rapid montage of everyday Soviet life, cutting between workers, machines, and urban transformation

Did You Know?

- This was the 18th installment in Vertov's revolutionary Kino-Pravda newsreel series, which ran from 1922 to 1925

- The unusually long and descriptive title reflects Vertov's practice of giving his films elaborate, conceptual names

- The Paris footage was extremely rare for Soviet productions of the time, suggesting either special permission or covert filming

- Mikhail Kalinin, who appears in the film, was a prominent Soviet politician and one of the original members of the Politburo

- The auto race segment was filmed during an actual Petrograd-Moscow race, making it both documentary and sports coverage

- Vertov considered the camera superior to the human eye, calling his technique 'kino-eye' or 'cine-eye'

- The newborn ceremony was a real ritual performed by workers' collectives to symbolize the creation of the 'new Soviet person'

- The film was distributed free to workers' clubs and factories as part of Soviet educational programming

- Vertov's wife Elizaveta Svilova was the primary editor, working closely with him to achieve the rapid montage effects

- The 299 meters in the title refers to the length of the film reel, not a physical distance

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics were divided about Vertov's work. Some praised his innovative techniques and ideological commitment, while others found his films too experimental and lacking in conventional narrative structure. The Kino-Pravda series was generally well-received within avant-garde circles but faced criticism from more traditional filmmakers who favored narrative cinema. International recognition came later, with Western critics rediscovering Vertov's work in the 1960s and recognizing him as a pioneer of documentary film. Modern film scholars view Kino-Pravda No. 18 as an important example of early Soviet montage theory and a crucial development in documentary cinema history.

What Audiences Thought

The film was primarily shown to workers' audiences in factories, clubs, and educational institutions as part of the Soviet state's cultural programming. These audiences generally appreciated the depictions of Soviet progress and everyday life, though the experimental techniques sometimes proved challenging for viewers accustomed to more conventional cinema. The rapid montage and abstract sequences were sometimes confusing to general audiences, leading to debates within Soviet cultural circles about the appropriate level of experimentation in educational films. Despite these challenges, the Kino-Pravda series remained popular enough to continue production for three years, suggesting it found appreciative audiences among Soviet workers and intellectuals.

Awards & Recognition

- None - Soviet newsreels were not part of the award system in 1924

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Futurist art movement

- Constructivism

- Dziga Vertov's own theoretical writings on 'cine-eye'

- Soviet montage theory

- Documentary traditions of the 1910s

- Newsreel formats from Western cinema

This Film Influenced

- Man with a Movie Camera (1929)

- Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927)

- The Man with a Movie Camera (1929)

- British Documentary Movement films of the 1930s

- Cinéma vérité films of the 1960s

- Direct Cinema documentaries

- Music video editing techniques

- Modern news and documentary programming

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Preserved in various film archives including the Russian State Film Archive (Gosfilmofond) and international collections. The film has been restored and digitized by several institutions, though some sequences may show deterioration typical of nitrate film from the 1920s. Complete versions are available through specialized film archives and some educational institutions.