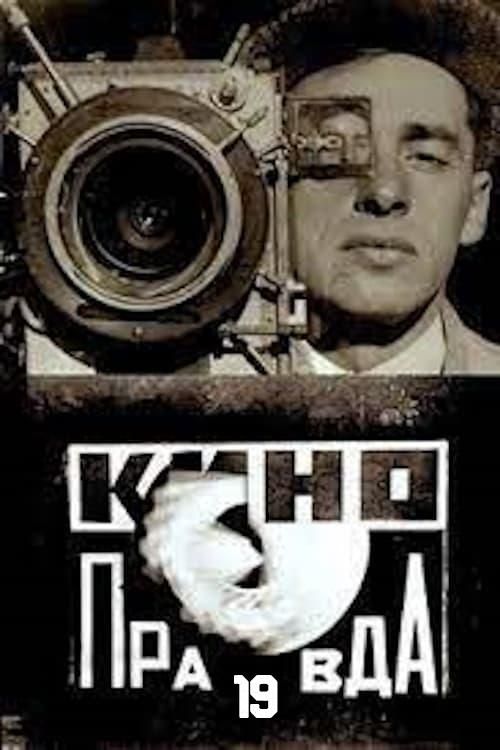

Kino-Pravda No. 19: A Movie-Camera Race Moscow – Arctic Ocean

Plot

This installment of Dziga Vertov's revolutionary Kino-Pravda series documents the vast geographical and social transformations occurring across the Soviet Union in 1924. The film creates a cinematic dialogue between contrasting elements of Soviet life - urban Moscow versus rural countryside, the warm southern regions versus the frozen Arctic north, summer activities versus winter conditions, and the evolving roles of peasant women versus working women in the new socialist society. Through rapid editing and juxtaposition of images, Vertov illustrates the interconnectedness of these seemingly disparate elements within the unified Soviet state. The documentary particularly emphasizes the emancipation of women, showing them participating in industrial labor, agricultural work, and political life as equals to men. The film serves as both a factual record and an artistic statement about the ambitious project of building socialism across the enormous expanse of the Soviet territories.

Director

About the Production

Filmed as part of the regular Kino-Pravda newsreel series, this entry required extensive travel across the Soviet Union to capture the geographical contrasts. Vertov and his camera operators faced significant logistical challenges, particularly in the Arctic segments where equipment had to function in extreme cold. The film exemplifies Vertov's theory of the 'cine-eye' - capturing life unawares and revealing truths invisible to the human eye through cinematic techniques. The production utilized portable cameras that were cutting edge for the time, allowing for more mobile and spontaneous filming than traditional documentary methods.

Historical Background

1924 was a pivotal year in the early Soviet Union, occurring during Lenin's final months and the beginning of Stalin's rise to power. The country was undergoing massive social and economic transformation following the civil war, with the New Economic Policy (NEP) allowing limited market mechanisms while the state maintained control of key industries. This period saw intense debate about the future direction of Soviet art and culture, with avant-garde filmmakers like Vertov competing with more traditional approaches. The emancipation of women was a central tenet of Bolshevik ideology, with laws granting equal rights, easier divorce, and state support for working mothers. The film's focus on connecting disparate regions of the vast Soviet territory reflected the political imperative of creating unity across the former Russian Empire's enormous geographical and ethnic diversity. Industrialization was beginning in earnest, and the Soviet state was keen to document and promote the transformation from a predominantly agricultural to an industrial society.

Why This Film Matters

Kino-Pravda No. 19 represents a crucial milestone in the development of documentary cinema and Soviet montage theory. Vertov's radical approach to filmmaking, which rejected theatrical conventions and embraced the camera's ability to reveal hidden truths, influenced generations of filmmakers from Jean Rouch to the cinéma vérité movement. The series established many techniques now standard in documentary filmmaging, including handheld camera work, location shooting, and rhythmic editing to create emotional and intellectual impact. The film's portrayal of women's emancipation, while propagandistic, documented a genuine social revolution that was unprecedented in its scope. Vertov's concept of the 'cine-eye' - suggesting the camera could see more truthfully than the human eye - challenged fundamental assumptions about reality and representation in media. The Kino-Pravda series as a whole helped establish the documentary as a legitimate artistic form rather than merely journalistic record, paving the way for the creative nonfiction films that would follow.

Making Of

The production of Kino-Pravda No. 19 exemplified Vertov's innovative approach to documentary filmmaking, which rejected traditional narrative structures in favor of what he called 'intervals' - the rhythmic relationships between shots. Vertov and his small crew, often including his wife Elizaveta Svilova as editor and brother Mikhail Kaufman as cinematographer, worked with minimal equipment but maximum creativity. They frequently filmed in dangerous conditions, particularly for the Arctic sequences where camera equipment could freeze and malfunction. The film's emphasis on women's emancipation was both a genuine reflection of Soviet social policy and a deliberate propaganda effort to showcase the supposed advantages of socialism over traditional society. Vertov's revolutionary editing techniques, which involved rapid cutting, superimposition, and rhythmic montage, were developed and refined through the Kino-Pravda series and would later influence the entire language of cinema.

Visual Style

The cinematography in Kino-Pravda No. 19 exemplifies Vertov's revolutionary approach to capturing reality. The film employs handheld cameras for unprecedented mobility, allowing shots from impossible angles and perspectives. Vertov and his team utilized extreme close-ups, low angles, and high angles to create dynamic visual rhythms. The Arctic segments demonstrate remarkable technical achievement, functioning in extreme cold and capturing images rarely seen by audiences of the time. The cinematography emphasizes contrast and movement, with shots of industrial machinery juxtaposed against natural landscapes, urban crowds against rural solitude. Vertov's famous 'cine-eye' philosophy is evident throughout - the camera becomes an active observer rather than a passive recorder, revealing patterns and connections invisible to casual observation.

Innovations

Kino-Pravda No. 19 showcased numerous technical innovations that would influence cinema for decades. Vertov pioneered the use of handheld cameras for documentary work, creating a sense of immediacy and intimacy impossible with stationary cameras. The film's rapid editing and montage techniques established new possibilities for creating meaning through the juxtaposition of images. Vertov experimented with superimposition, split screens, and other optical effects to create complex visual statements. The Arctic filming represented a significant technical achievement, demonstrating that cameras could operate effectively in extreme conditions. Vertov's development of what he called 'intervals' - the calculated relationships between shots based on length, content, and rhythm - represented a theoretical breakthrough in understanding film language. These technical innovations were not merely formal exercises but served Vertov's goal of creating a new form of truth-telling through cinema.

Music

As a silent film from 1924, Kino-Pravda No. 19 had no synchronized soundtrack. In Soviet cinemas of the period, it would have been accompanied by live musical performance, typically piano or small ensemble. The music would have been improvised or selected from existing classical pieces to match the rhythm and mood of the film. Some screenings might have included live narration or sound effects to enhance the viewing experience. Modern restorations and screenings often feature newly composed scores by contemporary musicians who interpret Vertov's rhythmic visual style through music. The absence of recorded sound actually enhanced Vertov's ability to create meaning through purely visual means, forcing him to develop sophisticated techniques of visual storytelling.

Famous Quotes

The kino-eye is a cinema-eye that sees more and better than the human eye

I am kino-eye, I am a mechanical eye

I am a machine that shows you the world as only I can see it

We proclaim the old films, based on romance, theatrical films and the like, to be leprous

From today on, we are liberating the camera and making it grow in the opposite direction - away from man

Memorable Scenes

- The rapid montage sequence contrasting Moscow's industrial activity with Arctic ice floes, creating a visual dialogue between human progress and natural extremes

- The sequence showing women working alongside men in factories and fields, intercut with traditional domestic scenes to emphasize social transformation

- The opening sequence establishing the film's geographical scope through a whirlwind tour of Soviet territories from south to north

Did You Know?

- Kino-Pravda No. 19 was part of a series of 23 newsreels released between 1922-1925, each typically 3-6 segments long

- The title 'Kino-Pravda' translates to 'Cinema Truth' in Russian, reflecting Vertov's documentary philosophy

- Vertov often used his brother Mikhail Kaufman as cinematographer for these newsreels

- The series was initially conceived as a weekly newsreel but production challenges made this impossible to maintain

- Many Kino-Pravda entries have been lost or only survive in fragments, making complete viewing rare

- The newsreels were typically shown before feature films in Soviet cinemas

- Vertov's editing techniques in these films influenced later documentary filmmakers worldwide

- The series was one of the first to use montage as a means of creating meaning beyond simple documentation

- Some segments were filmed using hidden cameras to capture authentic reactions

- The Arctic segments represented some of the earliest documentary footage filmed in such extreme conditions

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics were divided about Vertov's radical approach - some praised his innovative techniques and revolutionary zeal, while others found his work too abstract and difficult for mass audiences. The Kino-Pravda series was generally appreciated for its energy and technical innovation but criticized by more conservative filmmakers who favored narrative cinema. Western critics discovered Vertov's work much later, with the 1960s and 1970s bringing renewed appreciation for his contributions to film theory and practice. Modern film scholars universally recognize Kino-Pravda as foundational to documentary cinema, though they also acknowledge its role as Soviet propaganda. The series is now studied in film schools worldwide as an example of how technical innovation can serve both artistic and political purposes simultaneously.

What Audiences Thought

Original Soviet audiences in 1924 would have viewed Kino-Pravda No. 19 as part of a cinema program, typically before a feature film. The rapid editing and abstract montage techniques were challenging for many viewers accustomed to more straightforward narrative films. However, the newsreel format and focus on contemporary Soviet life made it relevant and engaging for audiences eager to see images of their transforming country. The segments showing women in new roles would have been particularly striking, as they visualized the social changes occurring in Soviet society. Modern audiences viewing the film today often find it formally challenging but historically fascinating, offering a window into both the Soviet Union of the 1920s and the birth of modern documentary techniques.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Bolshevik revolutionary theory

- Futurist art movement

- Constructivist design principles

- Lenin's writings on cinema

- Soviet newsreel traditions

- Avant-garde poetry

- Scientific documentary methods

This Film Influenced

- Man with a Movie Camera

- Berlin: Symphony of a Great City

- The Man with a Movie Camera

- Nanook of the North

- Chronicle of a Summer

- Primary

- Don't Look Back

- The Thin Blue Line

- Hoop Dreams

- The Act of Killing

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Like many early Soviet films, Kino-Pravda No. 19 exists in various states of preservation. Some sequences survive in excellent condition in Russian state archives, while others exist only in fragments or poor-quality copies. The film has been partially restored by film preservation institutions including Gosfilmofond and various international archives. Complete versions are rare, and many screenings combine material from different sources to create the most comprehensive version possible. The fragile nature of early nitrate film stock and the political upheavals of the 20th century contributed to the loss of some material. Digital restoration efforts continue to improve access to this historically significant work.