Man with a Movie Camera

"An Experiment in the Language of Cinema"

Plot

Man with a Movie Camera is a groundbreaking silent documentary that captures a day in the life of Soviet cities through the eyes of an omnipresent cameraman. The film follows Mikhail Kaufman (Vertov's brother) as he traverses urban landscapes with his camera, documenting the bustling streets, factories, and people of Moscow, Kyiv, and Odesa. Through innovative editing techniques, the film not only shows what the cameraman records but also reveals the process of filmmaking itself, including the development and editing of footage. The documentary presents a symphony of urban life, from the awakening of the city at dawn to its nighttime activities, all while celebrating the power of cinema to capture and transform reality. The film culminates in a spectacular display of cinematic techniques, including superimpositions, split screens, and rapid montages that push the boundaries of what film can achieve.

Director

Cast

About the Production

Filmed over approximately three years (1926-1929) using hidden cameras and innovative filming techniques. Vertov and his brother Mikhail Kaufman developed new methods for capturing candid footage, including camera disguises and portable equipment. The film was edited by Elizaveta Svilova, Vertov's wife, who created over 1,700 separate shots in the final cut. The production faced criticism from Soviet authorities for its 'formalist' approach, but was ultimately completed with state support.

Historical Background

Man with a Movie Camera emerged during the transformative period of late 1920s Soviet Union, a time of rapid industrialization and cultural experimentation following the Bolshevik Revolution. The film reflects the Soviet avant-garde movement's embrace of modernism and rejection of bourgeois art forms. Vertov's work coincided with the First Five-Year Plan (1928-1932), which emphasized industrialization and technological progress - themes prominently featured in the film. The late 1920s also saw the rise of Socialist Realism as the state-approved artistic style, making Vertov's experimental approach increasingly controversial. The film captured Soviet cities at a moment of profound change, with new construction, modern transportation, and evolving social dynamics. Its creation occurred just before the Stalinist crackdown on artistic experimentation that would soon force many avant-garde artists to conform or face persecution.

Why This Film Matters

Man with a Movie Camera revolutionized documentary filmmaking and influenced generations of directors across the globe. Its innovative editing techniques, including jump cuts, superimpositions, and split screens, prefigured many developments in modern cinema. The film's self-reflexive approach, showing the mechanics of filmmaking itself, established a new paradigm for meta-cinema that continues to influence contemporary filmmakers. Its urban focus and celebration of modernity resonated with later city symphonies and documentary traditions. The film's rejection of narrative conventions in favor of pure visual language expanded the possibilities of cinematic expression. Its influence can be seen in music videos, commercials, and experimental cinema that employ rapid montage and visual effects. The film has become a touchstone for discussions about documentary truth, the relationship between camera and reality, and the power of editing to shape perception.

Making Of

The making of Man with a Movie Camera was as revolutionary as the film itself. Vertov, born Denis Arkadievich Kaufman, adopted his pseudonym meaning 'spinning top' to reflect his dynamic approach to cinema. His brother Mikhail served as both cinematographer and on-screen subject, while their wife Elizaveta Svilova handled the complex editing. The trio, known as 'Kinoks' (cinema-eye people), rejected traditional narrative filmmaking in favor of capturing 'life as it is.' They developed portable cameras and disguised filming equipment to capture authentic urban life without people's awareness. The production involved extensive travel across Soviet cities, often under difficult conditions. Vertov's insistence on showing the filmmaking process itself, including editing scenes, was unprecedented and controversial. The relationship between the brothers deteriorated during production due to creative disagreements about the film's direction, with Mikhail eventually leaving the project before completion.

Visual Style

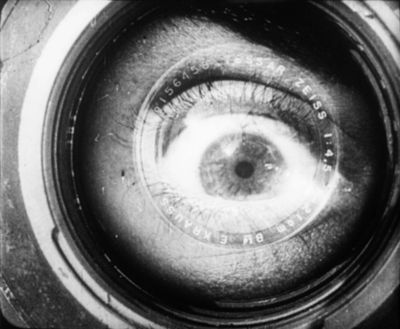

The cinematography in Man with a Movie Camera was revolutionary for its time, employing techniques that were decades ahead of contemporary practice. Mikhail Kaufman utilized extreme camera angles, including bird's-eye views and worm's-eye perspectives, to create dynamic urban perspectives. The film features extensive use of Dutch angles, rapid pans, and tracking shots that create a sense of movement and energy. Kaufman employed innovative camera mounts on vehicles, trams, and even moving trains to capture fluid motion. The cinematography includes famous self-reflexive shots of the camera itself, including the iconic image of Kaufman's camera perched atop another camera. The use of superimposition and multiple exposure created surreal visual effects that emphasized the film's experimental nature. The cinematography deliberately breaks the illusion of reality by showing the camera's presence, establishing a new relationship between filmmaker, subject, and audience.

Innovations

Man with a Movie Camera pioneered numerous technical innovations that would become standard in filmmaking. The film introduced complex editing techniques including jump cuts, match cuts, and rapid montage sequences. Vertov and his team developed specialized camera equipment, including portable cameras and hidden mounts for candid filming. The film's use of superimposition and multiple exposure created visual effects that were technically advanced for the period. The editing process involved over 1,700 separate shots, requiring unprecedented organizational precision. The film demonstrated early use of what would later be called visual effects, including stop-motion animation and time-lapse photography. The self-reflexive elements, showing the filmmaking process itself, were technically innovative in their execution. The film's urban sequences required innovative approaches to capturing moving subjects, leading to advances in mobile camera techniques.

Music

Originally conceived as a silent film, Man with a Movie Camera has received numerous musical scores over the decades. Vertov himself provided detailed instructions for musical accompaniment, suggesting specific rhythms and themes for different sequences. In 1995, the Alloy Orchestra created a celebrated score using found objects and percussion instruments to match the film's industrial themes. The Cinematic Orchestra released a highly regarded soundtrack in 2003 that became influential in its own right. Michael Nyman composed a score in 2002 that emphasized the film's urban rhythms. Contemporary screenings often feature live musical accompaniment, with various musicians and ensembles creating new interpretations. The absence of synchronized sound in the original version allowed for greater flexibility in musical interpretation, making each viewing potentially unique.

Famous Quotes

"I am kino-eye, I am a mechanical eye. I, a machine, show you the world as only I can see it." - Dziga Vertov's manifesto

"This film is an experiment in cinematic communication of real events without the aid of intertitles, without the aid of a story, without the aid of theatre." - Opening intertitle

"The 'Man with a Movie Camera' is a film poem about the beauty of everyday life." - Dziga Vertov

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing an empty movie theater gradually filling with an audience, establishing the film's self-reflexive nature

- The famous split-screen sequence showing multiple perspectives of the same street scene simultaneously

- The superimposed camera appearing to grow from a beer glass, exemplifying the film's surreal visual effects

- The rapid montage of Soviet citizens from all walks of life, culminating in a unified vision of the new Soviet man

- The final sequence showing the camera itself as the hero, with superimposed images celebrating the power of cinema

Did You Know?

- The film contains no intertitles explaining the action, which was revolutionary for documentary films of its time

- Mikhail Kaufman, the cameraman featured in the film, was Dziga Vertov's brother and their professional relationship eventually soured over creative differences

- The film was banned in some Western countries for decades due to its perceived Soviet propaganda content

- Vertov originally wanted to call the film 'The Sixth Part of the World' but changed it during production

- The famous self-reflexive scene showing the cameraman filming himself was one of the earliest examples of breaking the fourth wall in cinema

- The film features approximately 1,775 separate shots, an unprecedented number for its time

- Vertov and his team invented several camera techniques specifically for this film, including camera mounts for vehicles and hidden cameras

- The film was shot without a script or predetermined shooting schedule, following Vertov's theory of 'life caught unawares'

- The famous scene of the camera superimposed on beer glasses was achieved through multiple exposure techniques developed for the film

- The film's editing took nearly as long as the shooting, with Svilova working tirelessly to create the complex montages

What Critics Said

Initial critical reception was deeply divided. Soviet critics, particularly those aligned with emerging Socialist Realist doctrine, condemned the film as 'formalist' and disconnected from proletarian concerns. However, avant-garde circles praised its technical innovation and artistic daring. Western critics were initially slow to recognize the film's significance, with many dismissing it as propaganda. Over time, critical opinion shifted dramatically, with the film now widely regarded as a masterpiece of cinematic art. Contemporary critics celebrate its technical achievements, theoretical sophistication, and enduring influence. The film regularly appears in greatest films lists, with Sight & Sound magazine ranking it among the top documentaries ever made. Modern critics particularly praise its editing innovations and its exploration of the relationship between cinema and reality.

What Audiences Thought

Initial Soviet audience reception was mixed, with many viewers finding the film's abstract style confusing compared to more conventional Soviet cinema. The lack of narrative and intertitles challenged audience expectations of the time. However, urban audiences and intellectuals appreciated its dynamic portrayal of modern Soviet life. The film found greater appreciation in international avant-garde circles and among filmmakers who recognized its technical innovations. Contemporary audiences, particularly those interested in film history and experimental cinema, have embraced the film as a groundbreaking work. Modern screenings often feature live musical accompaniment, enhancing the viewing experience. The film has gained cult status among film students and experimental cinema enthusiasts, with many considering it essential viewing for understanding cinematic language.

Awards & Recognition

- Named one of the Top 10 films of all time by Sight & Sound magazine's critics' poll (2012)

- Voted the 8th greatest documentary ever made by the International Documentary Association (2014)

- Preserved in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress (2021)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Ballet Mécanique (1924)

- Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927)

- The Man with a Movie Camera was influenced by Vertov's earlier Kino-Pravda newsreels

- Futurist art movement

- Constructivist design principles

This Film Influenced

- Koyaanisqatsi (1982)

- Baraka (1992)

- Powaqqatsi (1988)

- The Matrix (1999) - for its self-reflexive elements

- Run Lola Run (1998) - for rapid editing techniques

- Scott Pilgrim vs. The World (2010) - for visual experimentation

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved and restored by various archives including the British Film Institute and the Museum of Modern Art. Multiple versions exist due to different restoration efforts and varying running times. The most complete version was restored from original negatives in the early 2000s. The film is considered well-preserved compared to many silent-era works, though some degradation is evident in surviving prints. Digital restorations have made the film accessible to modern audiences while preserving its historical significance.