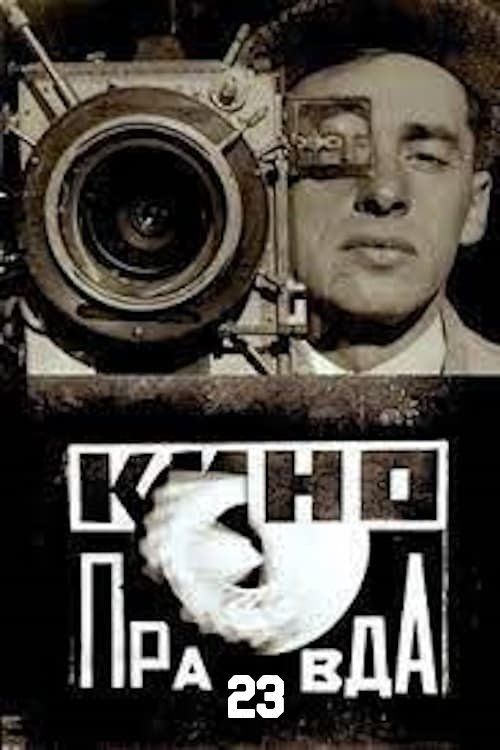

Kino-Pravda No. 23: Radio Pravda

Plot

Kino-Pravda No. 23: Radio Pravda depicts the Soviet Union's efforts to bring radio technology to the rural peasantry as a tool of communication and propaganda. The film follows a peasant as he purchases a radio receiver from a shop and receives instructions on how to install an antenna. It documents the development of a broadcast station and shows the transmission of a concert performance to remote areas. The film includes innovative sequences showing radio waves penetrating a traditional Russian log hut (izba), symbolizing the penetration of modern technology and Soviet ideology into rural life. Through Aleksandr Bushkin's time-lapse animation and Vertov's characteristic montage techniques, the film celebrates radio as a magical medium capable of uniting the vast Soviet territories.

Director

About the Production

This was the final installment of Dziga Vertov's influential Kino-Pravda newsreel series that ran from 1922-1925. The film incorporated innovative techniques including time-lapse animation by Aleksandr Bushkin and special effects showing radio waves. Only approximately one-third of the original footage survives today, with the rest presumed lost. The production was part of the Soviet state's efforts to promote technological modernization and political education among the largely illiterate peasant population.

Historical Background

1925 was a period of relative stability and economic recovery in the Soviet Union following the civil war and famine, known as the New Economic Policy (NEP) era. Radio technology was rapidly expanding as a tool for mass communication and political education in a country with vast distances and low literacy rates. The Soviet government invested heavily in building radio infrastructure, seeing it as a means to transmit Communist ideology directly to peasants and workers without relying on print media. This film emerged during Vertov's most productive period, when he was developing his theories of documentary cinema and challenging traditional narrative filmmaking. The Kino-Pravda series itself represented a revolutionary approach to news reporting, using cinema to create what Vertov called a 'fresh perception of the world.' The film also reflects the Soviet fascination with technology and modernization as tools for building socialism.

Why This Film Matters

Kino-Pravda No. 23 represents a crucial document of both Soviet media history and the development of documentary cinema. As part of Vertov's Kino-Pravda series, it helped establish the language of documentary filmmaking, particularly the use of montage to create meaning and emotional impact. The film exemplifies the Soviet avant-garde's belief in art's power to shape consciousness and build a new socialist society. Its innovative visualization of radio waves and use of animation influenced subsequent generations of filmmakers working at the intersection of documentary and experimental cinema. The film also serves as a valuable historical record of early Soviet efforts to use mass media for political education and social transformation. Vertov's approach to capturing 'life unawares' and his rejection of theatrical conventions influenced documentary movements worldwide, from cinéma vérité to direct cinema. The surviving footage provides insight into how Soviet propaganda sought to present technology as magical and beneficial rather than threatening, attempting to overcome traditional peasant resistance to modernization.

Making Of

Kino-Pravda No. 23 was produced during a period of intense experimentation in Soviet cinema, following Lenin's directive that cinema was 'the most important of the arts' for political education. Vertov and his team, including his brother Mikhail Kaufman (cinematographer) and wife Elizaveta Svilova (editor), worked as a collective known as 'The Council of Three.' They would often travel with portable equipment to capture authentic footage across the Soviet Union. The radio sequences required technical ingenuity to visualize invisible radio waves, likely using multiple exposures and animation techniques. The production faced the typical challenges of early Soviet filmmaking, including limited resources, primitive equipment, and the need to operate in often harsh conditions, especially when filming in rural areas. The film's focus on radio technology reflected the Soviet government's massive investment in broadcasting infrastructure as a means to overcome the country's vast distances and widespread illiteracy.

Visual Style

The cinematography in Kino-Pravda No. 23 exemplifies Vertov's revolutionary approach to documentary filmmaking. Mikhail Kaufman, Vertov's brother and frequent collaborator, likely served as cinematographer, employing the 'kino-glaz' (camera eye) philosophy of capturing life without interference. The film features a mix of observational footage of peasants interacting with radio technology, staged demonstrations of installation procedures, and innovative special effects sequences. The most remarkable cinematographic achievement is the visualization of radio waves penetrating a cross-section of a traditional Russian izba, requiring complex technical solutions to make invisible forces visible. Time-lapse photography, possibly created by Aleksandr Bushkin, adds a dynamic element to sequences showing technological processes. Vertov's characteristic rapid montage creates rhythmic patterns and intellectual connections between disparate images, transforming simple documentary footage into a sophisticated cinematic argument about technology's transformative power.

Innovations

Kino-Pravda No. 23 showcases several technical innovations that were groundbreaking for 1925. The film's most notable achievement is the visualization of radio waves, which required creative use of special effects to make invisible electromagnetic forces visible to cinema audiences. This likely involved multiple exposures, animation techniques, and possibly matte photography to create the illusion of waves penetrating a building. The time-lapse animation by Aleksandr Bushkin represents an early example of this technique in Soviet documentary cinema. Vertov's use of rapid montage to create intellectual and emotional connections between images pushed the boundaries of cinematic language. The film also demonstrates the portability and flexibility of Soviet camera equipment of the era, which allowed Vertov's team to film in various locations from urban radio shops to rural peasant homes. The surviving footage shows sophisticated understanding of continuity editing and spatial relationships, particularly in the instructional sequences showing antenna installation.

Music

As a silent film, Kino-Pravda No. 23 would have been accompanied by live music during theatrical screenings. Soviet cinemas typically employed pianists or small ensembles to provide musical accompaniment, often using compiled scores that mixed popular songs, classical excerpts, and specially composed cues. The music would have emphasized the film's celebratory tone during sequences showing radio technology's benefits, while creating tension or wonder during the special effects sequences. Some screenings might have included sound effects created live in the theater, particularly for the radio wave visualization. Vertov was deeply interested in the relationship between sound and image, and his later work with sound film in the 1930s would build on these early experiments with musical accompaniment. The surviving footage lacks its original musical context, but modern screenings often use period-appropriate Soviet music or newly composed scores to recreate the intended viewing experience.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film with no intertitles documented in the surviving footage, specific quotes are not available. However, Vertov's theoretical writings from this period include: 'The camera eye is more perfect than the human eye', and 'I am kino-eye, I am a mechanical eye. I, a machine, show you the world as only I can see it.'

Memorable Scenes

- The sequence showing radio waves visually penetrating a cross-section of a traditional Russian peasant hut (izba), which film scholar Yuri Tsivian described as 'a cross-section of a photographically correct izba is penetrated by schematically charted radio waves'

- Aleksandr Bushkin's time-lapse animation sequences demonstrating technological processes

- The instructional segment showing a peasant learning to install a radio antenna

- The concert broadcast sequence demonstrating radio's ability to transmit culture to remote areas

- The opening scene of a peasant purchasing a radio receiver, symbolizing the accessibility of new technology

Did You Know?

- This was the 23rd and final issue of Vertov's groundbreaking Kino-Pravda newsreel series

- Only about one-third of the original film survives today, with the remaining footage lost to time

- The film features innovative time-lapse animation by Aleksandr Bushkin, one of the earliest examples of this technique in Soviet cinema

- The sequence showing radio waves penetrating a traditional Russian izba was created using special effects to visualize the invisible technology

- The title 'Radio Pravda' connects to 'Pravda,' the official newspaper of the Communist Party, emphasizing radio as a new medium for spreading truth

- Vertov's wife and collaborator, Elizaveta Svilova, likely edited the film as she did most of his works

- The film was part of a broader Soviet campaign to modernize rural areas and connect them to urban centers

- Kino-Pravda newsreels were typically shown before feature films in Soviet cinemas

- The film exemplifies Vertov's theory of 'kino-glaz' or 'camera eye,' capturing life as it happens without theatrical staging

- Radio technology was still relatively new in 1925, making this film a celebration of cutting-edge communications

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics generally praised the Kino-Pravda series for its innovative approach and political utility, though some found Vertov's experiments too radical. The film was recognized as an effective tool for promoting radio technology to skeptical rural populations. Western critics at the time had limited access to Soviet newsreels, but those who encountered Vertov's work noted its formal innovations. Modern film historians and scholars consider Kino-Pravda No. 23 significant for its technical achievements and as an example of Vertov's developing cinematic language. Critics particularly note the ingenious visualization of radio waves and the film's role in Vertov's evolution toward his masterpiece 'Man with a Movie Camera' (1929). The fragmentary nature of the surviving footage has led to scholarly debate about the film's original structure and complete content, with some viewing it as a tantalizing glimpse of Vertov's lost genius.

What Audiences Thought

Soviet audiences in the 1920s encountered Kino-Pravda newsreels as part of cinema programs, where they served both as news and educational content. Urban audiences likely appreciated the celebration of modern technology, while rural viewers may have found the radio sequences both fascinating and intimidating. The film's clear demonstration of how to install and use radio equipment would have been particularly valuable for peasants unfamiliar with the technology. As with many propaganda films of the era, genuine audience reactions are difficult to document accurately, but the continued production of the Kino-Pravda series suggests it was considered effective by Soviet authorities. The film's focus on practical benefits of radio technology—such as access to music and news—would have appealed to audiences hungry for entertainment and information. Modern audiences encountering the surviving footage typically respond with fascination to its innovative techniques and historical significance, though the fragmentary nature of what remains can make full appreciation challenging.

Awards & Recognition

- No specific awards documented for this individual newsreel installment

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Vertov's earlier Kino-Pravda newsreels

- Soviet constructivist art and design theory

- Lenin's writings on cinema as a political tool

- Futurist celebration of technology and speed

- D.W. Griffith's editing techniques

- European avant-garde film movements

- Soviet montage theory as developed by Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Kuleshov

This Film Influenced

- Vertov's later 'Man with a Movie Camera' (1929)

- Soviet propaganda films of the 1930s

- Documentary films using animation to explain technical processes

- Educational films demonstrating new technologies

- Newsreel formats worldwide

- Cinéma vérité and direct cinema movements

- Music videos using rapid montage techniques

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Only approximately one-third of the original film survives today. The missing footage is presumed lost, a common fate for early Soviet films due to inadequate storage conditions, neglect, and the deterioration of nitrate film stock. The surviving fragments are preserved in various film archives, including the Gosfilmofond in Russia. Some restoration work has been done on the surviving footage, but the complete film as originally intended by Vertov is likely lost forever. The fragmentary nature of what remains makes it difficult to fully appreciate Vertov's complete vision for this installment of Kino-Pravda.