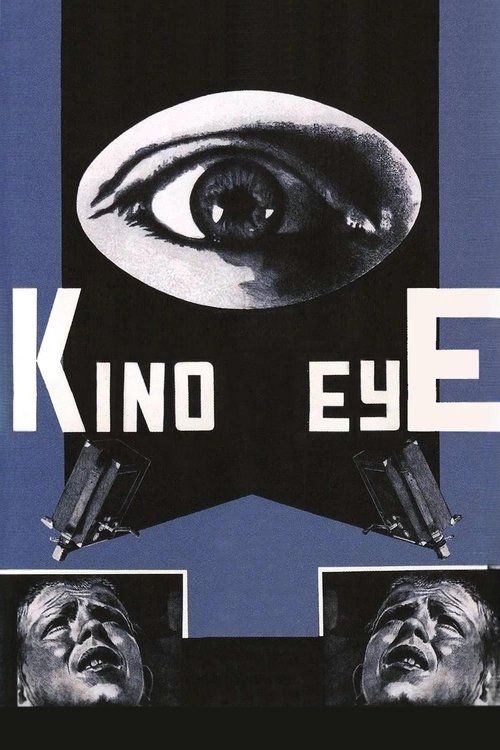

Kino Eye

Plot

Dziga Vertov's 'Kino Eye' presents a revolutionary vision of Soviet life through the lens of the Young Pioneers, the youth organization dedicated to building socialism. The film follows these industrious children as they engage in various community activities: plastering propaganda posters across village walls, distributing handbills advocating cooperative shopping over private markets, promoting temperance campaigns, and assisting impoverished widows in their daily struggles. Vertov interweaves these documentary sequences with groundbreaking experimental segments, most notably the famous reverse-motion sequences showing a bull being 'un-slaughtered' and bread being 'un-baked,' challenging conventional cinematic reality. The film culminates in a powerful demonstration of collective action as the Young Pioneers organize a community festival, embodying the socialist ideals of cooperation and progress. Through its innovative techniques and propagandistic content, 'Kino Eye' presents both a celebration of Soviet achievements and a manifesto for the transformative power of cinema itself.

Director

About the Production

Filmed during the New Economic Policy (NEP) period, 'Kino Eye' was created with limited resources and primitive equipment. Vertov and his crew, including his brother Mikhail Kaufman as cinematographer, often had to improvise with available technology. The film was shot over several months in 1924, with Vertov insisting on capturing authentic moments of Soviet life rather than staging scenes. The reverse-motion sequences required precise planning and multiple takes to achieve the desired effect of time reversal.

Historical Background

'Kino Eye' was created during a pivotal period in Soviet history - the New Economic Policy (NEP) era of the early 1920s, when Lenin's government allowed limited private enterprise while maintaining state control of key industries. This was also the formative period of Soviet cinema, with filmmakers like Vertov, Eisenstein, and Pudovkin developing new cinematic languages to serve the revolutionary cause. The film emerged at a time when the Soviet Union was actively promoting literacy, collectivization, and the formation of new social institutions like the Young Pioneers. Vertov's work reflected the Bolshevik belief that cinema could be a powerful tool for education and propaganda, capable of shaping the consciousness of the new Soviet citizen. The film's emphasis on collective action and community service mirrored the government's efforts to build socialist consciousness among the population, particularly the youth who would inherit the revolution.

Why This Film Matters

'Kino Eye' represents a landmark in the development of documentary cinema and film theory. Vertov's radical approach to filmmaking, rejecting traditional narrative structures in favor of what he called 'cine-truth,' influenced generations of filmmakers across the world. The film's innovative editing techniques, use of montage, and experimental camera work demonstrated cinema's potential as an art form capable of capturing and shaping reality. Its influence can be seen in the works of later documentary filmmakers like D.A. Pennebaker, the Maysles brothers, and even modern reality television. The film also exemplifies the avant-garde movement in early Soviet cinema, which sought to create a new visual language appropriate to the revolutionary society it depicted. Vertov's concept of the 'Kino-Eye' - the camera as a superior mechanical eye capable of perceiving truth beyond human limitations - became a foundational theory in documentary studies and continues to influence discussions about the relationship between cinema and reality.

Making Of

The production of 'Kino Eye' was marked by Vertov's uncompromising vision and experimental approach to filmmaking. Working with his brother Mikhail Kaufman as cinematographer, Vertov rejected traditional narrative cinema in favor of what he called 'life caught unawares.' The crew often had to conceal their cameras to capture spontaneous reactions, sometimes using hidden cameras disguised as everyday objects. The reverse-motion sequences were particularly challenging to execute, requiring precise coordination and multiple takes. Vertov insisted on using real workers, peasants, and Young Pioneers rather than professional actors, believing this would lend greater authenticity to the film's message. The editing process, overseen by Elizabeth Svilova, took months as Vertov experimented with various montage techniques to create rhythm and meaning through the juxtaposition of images. The film was made under difficult conditions, with frequent equipment malfunctions and limited film stock, yet Vertov's determination to realize his cinematic vision never wavered.

Visual Style

Mikhail Kaufman's cinematography in 'Kino Eye' broke new ground in documentary filmmaking through its innovative camera techniques and visual strategies. The film employs a variety of unconventional camera angles and movements, including low-angle shots to emphasize the dignity of labor and dynamic tracking shots that create a sense of movement and progress. Kaufman utilized both stationary and moving cameras, sometimes mounting them on bicycles, cars, or even moving trains to capture the rhythm of Soviet life. The cinematography frequently juxtaposes close-ups of human faces with wide shots of collective activities, creating a visual dialogue between individual and society. The famous reverse-motion sequences required meticulous planning and execution, with Kaufman having to film processes in their entirety and then reverse them in post-production. The visual style emphasizes geometric compositions and industrial motifs, reflecting the modernist aesthetic prevalent in early Soviet art. Kaufman's approach to cinematography embodied Vertov's Kino-Eye theory, using the camera not merely to record reality but to reveal hidden patterns and meanings within everyday life.

Innovations

'Kino Eye' introduced numerous technical innovations that would influence cinema for decades. The film's pioneering use of reverse motion effects, particularly in the 'un-slaughtering' and 'un-baking' sequences, demonstrated new possibilities for temporal manipulation in cinema. Vertov and his team developed innovative camera mounting techniques, allowing for dynamic movement through industrial and urban spaces. The film's complex montage sequences, created through meticulous frame-by-frame editing, established new possibilities for creating meaning through the juxtaposition of images. The use of hidden cameras and candid photography techniques anticipated later developments in observational documentary filmmaking. The film also experimented with superimposition and multiple exposure techniques to create layered visual metaphors. Vertov's approach to sound synchronization, though the film was silent, anticipated later developments in audio-visual cinema through his theoretical writings on the relationship between image and sound. These technical achievements were not merely formal experiments but served Vertov's larger goal of creating a new cinematic language appropriate to the revolutionary society it depicted.

Music

As a silent film, 'Kino Eye' was originally presented without a synchronized soundtrack, though it would have been accompanied by live musical performances during theatrical exhibitions. The musical accompaniment varied depending on the venue and could range from a single pianist to a full orchestra. In some Soviet theaters, the film was accompanied by specially composed music that emphasized the revolutionary themes and industrial rhythms depicted on screen. Vertov himself was known to provide detailed instructions for musical accompaniment, suggesting specific moods and rhythms for different sequences. Modern restorations of the film have featured newly composed scores by contemporary musicians who attempt to capture the spirit of the original performances while incorporating modern musical sensibilities. These contemporary soundtracks often blend classical elements with electronic and experimental music, reflecting the film's avant-garde nature and its continuing relevance to modern audiences.

Famous Quotes

I am kino-eye, I am a mechanical eye. I, a machine, show you the world as only I can see it.

The camera's eye is more perfect than the human eye.

We cannot improve the making of life, but by showing it in a new way, we can change it.

Cinema is the art of organizing the necessary movements of objects in space as a rhythmical artistic whole.

The kino-eye lives and moves in time and space; it gathers and records impressions in a manner wholly different from that of the human eye.

Memorable Scenes

- The iconic reverse-motion sequence showing a bull being 'un-slaughtered' and coming back to life, symbolizing the possibility of reversing the processes of death and decay through socialist progress

- The 'un-baking bread' sequence where loaves of bread miraculously reassemble themselves from crumbs and return to their raw ingredients, demonstrating cinema's power to reveal hidden processes

- The montage of Young Pioneers enthusiastically distributing propaganda posters throughout the village, their youthful energy embodying the revolutionary spirit

- The cooperative shopping sequence where citizens are encouraged to buy from state-run stores rather than private markets, illustrating the film's propagandistic purpose

- The final community festival sequence showing collective celebration and cooperation, bringing together all the film's themes in a joyous display of Soviet achievement

Did You Know?

- The title 'Kino Eye' (Kinoglaz) refers to Vertov's theoretical concept that the camera eye could see more truthfully and comprehensively than the human eye

- The film features Vertov's wife Elizabeth Svilova as an editor, who would later become his primary collaborator on 'Man with a Movie Camera'

- The famous 'un-baking bread' sequence required the crew to film the entire bread-making process in reverse, starting with finished loaves and working backward through the steps

- The Young Pioneers featured in the film were actual members of the organization, not professional actors

- Vertov originally conceived 'Kino Eye' as part of a larger series of films exploring his Kino-Eye theory

- The film was initially controversial among Soviet critics who found its experimental techniques too 'bourgeois' and formalist

- Many of the propaganda posters shown in the film were created specifically for the production

- The film's editing style influenced generations of documentary filmmakers, particularly the British Documentary Film Movement of the 1930s

- Vertov used hidden cameras for some sequences to capture more authentic reactions from subjects

- The cooperative store featured in the film was a real establishment, temporarily enhanced for filming

What Critics Said

Initial Soviet critical reception to 'Kino Eye' was mixed, with some critics praising its innovative techniques while others accused Vertov of formalism and excessive experimentation. The film's rejection of traditional narrative structure and its avant-garde editing style were seen by some as too 'bourgeois' and insufficiently accessible to the masses. However, international avant-garde circles quickly recognized the film's significance, with European filmmakers and critics praising its bold visual experimentation. Over time, 'Kino Eye' has been reevaluated as a masterpiece of early documentary cinema, with modern critics recognizing its profound influence on the development of film language. Contemporary scholars view the film as a crucial document of both Soviet cinematic innovation and the broader avant-garde movement of the 1920s. The film is now widely studied in film schools and appreciated for its technical brilliance and its role in establishing documentary cinema as a legitimate artistic medium.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary Soviet audience reception to 'Kino Eye' is difficult to document precisely, but reports suggest that many viewers found the film's experimental techniques confusing and its non-linear structure challenging. The film's avant-garde nature meant it appealed primarily to educated urban audiences and film enthusiasts rather than the broader working-class audience it was ostensibly made for. However, the sequences showing Young Pioneers engaged in community activities reportedly resonated with viewers who recognized similar scenes from their daily lives. In subsequent decades, as the film gained recognition as a classic of world cinema, it found appreciative audiences among film students, historians, and enthusiasts of experimental cinema. Today, the film is primarily viewed in academic settings and film archives, where its historical significance and technical innovations are properly contextualized and appreciated.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were recorded for this film during its initial release period

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The writings of Vladimir Lenin on cinema as propaganda

- Futurist art movements of the 1910s and 1920s

- Constructivist art theory

- Dziga Vertov's own earlier newsreel work for Kino-Nedelya

- The theoretical writings of formalist critics like Viktor Shklovsky

This Film Influenced

- Man with a Movie Camera (1929) - Vertov's own masterpiece

- Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927) by Walter Ruttmann

- The City (1939) by Ralph Steiner and Willard Van Dyke

- Night Mail (1936) by Basil Wright and Harry Watt

- Don't Look Back (1967) by D.A. Pennebaker

- Salesman (1969) by Albert and David Maysles

- Koyaanisqatsi (1982) by Godfrey Reggio

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved through the efforts of various film archives, most notably the Gosfilmofond in Russia and international archives like the British Film Institute. Multiple versions and restorations exist, with the most complete versions running approximately 68 minutes. The film has survived in relatively good condition compared to other Soviet films of the era, thanks to its recognition as an important work of cinematic art. Several digital restorations have been undertaken in the 21st century, making the film accessible to modern audiences while preserving its historical and artistic significance. Some original footage remains lost or damaged, but the essential structure and content of Vertov's vision remains intact.