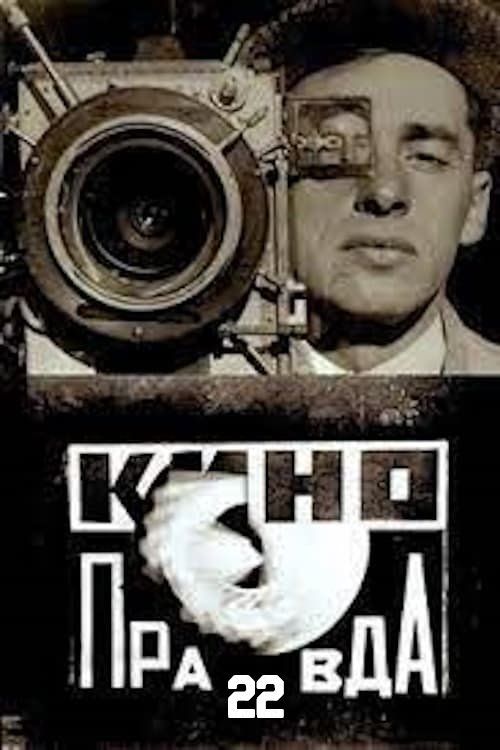

Kino-Pravda No. 22: Lenin Is Alive in the Heart of the Peasant. A Film Story

Plot

This installment of Dziga Vertov's revolutionary Kino-Pravda series documents the first anniversary of Vladimir Lenin's death in January 1925, capturing the profound impact his legacy had on the Soviet peasantry. The film follows a delegation of peasants as they journey from their rural villages to Moscow to participate in commemorative ceremonies, providing a stark visual contrast between countryside and urban Soviet life. Through Vertov's characteristic montage techniques and observational style, the documentary reveals how Lenin's revolutionary ideas have transformed the consciousness and aspirations of agricultural workers who were once among Russia's most oppressed populations. The film interweaves footage of the peasant delegation's Moscow visit with scenes of rural life, industrial progress, and collective mourning, creating a powerful visual argument for Lenin's enduring influence on the new Soviet society. Vertov employs his signature 'cine-eye' philosophy to capture authentic moments of peasant interaction with urban Soviet modernity, suggesting that Lenin's revolutionary spirit lives on not in monuments, but in the hearts and actions of the common people.

Director

About the Production

This film was part of Vertov's ongoing Kino-Pravda series, which he began in 1922 as a revolutionary approach to newsreel cinema. The production involved mobile camera teams traveling with the peasant delegation to capture authentic moments of their journey. Vertov and his brother Mikhail Kaufman (the primary cinematographer) employed portable cameras to achieve unprecedented mobility and intimacy in their documentary footage. The film was shot on 35mm film and processed at Goskino facilities in Moscow. Vertov's production philosophy rejected traditional narrative structure in favor of what he called 'intervals' - the rhythmic organization of visual material through montage to create new meanings and emotional responses.

Historical Background

This film was created during a crucial period in Soviet history, just one year after Vladimir Lenin's death and during the early years of Joseph Stalin's rise to power. 1925 marked the consolidation of Soviet power following the civil war, and the government was actively engaged in building the cult of Lenin as a revolutionary icon. The New Economic Policy (NEP) was still in effect, creating a complex economic situation that mixed elements of state control with limited market mechanisms. The film reflects the Soviet emphasis on the alliance between workers and peasants (the 'smychka') as the foundation of the revolutionary state. Cinema was recognized by Soviet leaders as a powerful tool for education and propaganda, with Lenin famously stating that 'of all the arts, for us the cinema is the most important.' The mid-1920s saw an explosion of creativity in Soviet cinema, with filmmakers like Vertov, Eisenstein, and Pudovkin developing innovative techniques that would influence world cinema. This period also saw intense debates about the proper role of cinema in building socialism, with Vertov's documentary approach representing one pole of these discussions.

Why This Film Matters

Kino-Pravda No. 22 represents a landmark in documentary cinema history and exemplifies Vertov's revolutionary approach to filmmaking. The film's emphasis on capturing reality through the 'cine-eye' influenced generations of documentary filmmakers, from the British Documentary Movement of the 1930s to the cinéma vérité practitioners of the 1960s. Vertov's innovative editing techniques, particularly his use of rhythmic montage to create meaning and emotional impact, contributed significantly to the development of film language and montage theory. The film also serves as an important historical document of Soviet efforts to build a new socialist consciousness among the peasantry and to create the cult of Lenin following his death. Its focus on the 'smychka' (alliance) between city and countryside reflects core Soviet ideological concerns of the 1920s. The Kino-Pravda series as a whole revolutionized the concept of newsreel cinema, transforming it from simple reportage into a vehicle for artistic expression and ideological persuasion. Vertov's work influenced not just documentary filmmakers but also experimental and avant-garde cinema movements worldwide, with his theories about the camera's ability to reveal truth continuing to resonate in contemporary discussions about media and reality.

Making Of

The production of Kino-Pravda No. 22 involved Vertov's innovative mobile filming techniques, which were revolutionary for the time. Vertov and his team, including his brother Mikhail Kaufman as cinematographer, used portable cameras that could be easily moved to capture spontaneous moments of the peasant delegation's journey. The filming process was highly experimental, with Vertov encouraging his camera operators to seek out unusual angles and perspectives that would reveal the 'truth' of Soviet life. The editing process, overseen by Vertov's wife Elizaveta Svilova, was equally innovative, employing rapid montage and rhythmic editing techniques to create emotional and political impact. The production team faced significant logistical challenges in coordinating with the peasant delegation and capturing both their rural origins and urban experiences. Vertov was known for his demanding working methods and his insistence on capturing authentic, unstaged moments, which often put him at odds with Soviet authorities who preferred more controlled propaganda. The film's creation coincided with a period of intense debate within Soviet cinema about the role and methods of revolutionary filmmaking, with Vertov's documentary approach competing against more conventional narrative films.

Visual Style

The cinematography in Kino-Pravda No. 22 exemplifies Vertov's revolutionary approach to documentary filmmaking, employing innovative techniques that were groundbreaking for the mid-1920s. Mikhail Kaufman, Vertov's brother and primary cinematographer, used portable cameras to achieve unprecedented mobility, allowing for intimate coverage of the peasant delegation's journey from rural areas to Moscow. The film features a variety of camera techniques including low angles, high angles, and dynamic movement that create visual interest and convey specific ideological meanings. Vertov and Kaufman experimented with extreme close-ups, rapid camera movements, and unusual perspectives to reveal what they called the 'invisible world' of reality. The cinematography emphasizes contrasts between rural and urban life, traditional and modern ways of living, and individual and collective experiences. The visual style is characterized by its raw, unpolished quality that Vertov considered essential to capturing truth, rejecting the artificiality of conventional narrative cinema. The camera work often focuses on machines, industry, and the physical labor of both peasants and workers, reflecting the Soviet celebration of industrial progress and the dignity of labor.

Innovations

Kino-Pravda No. 22 showcases several technical innovations that were groundbreaking for mid-1920s cinema. Vertov and his team developed and refined portable camera equipment that allowed for unprecedented mobility in documentary filming, enabling them to capture spontaneous moments in various locations from rural villages to urban Moscow. The film exemplifies Vertov's pioneering use of rapid montage editing, creating rhythmic patterns and intellectual associations between shots that went beyond simple narrative continuity. The production team experimented with multiple camera angles and perspectives, including low angles that emphasized the dignity of workers and peasants and dynamic camera movements that captured the energy of Soviet life. The film's editing techniques, particularly what Vertov called 'intervals' - the precise calculation of the duration between shots - represented a significant advancement in film language and montage theory. The technical approach emphasized authenticity over polish, with Vertov deliberately avoiding studio lighting and artificial setups in favor of natural conditions that he believed revealed truth more effectively. These technical innovations influenced not just documentary filmmaking but also narrative cinema, with directors like Eisenstein adapting and developing Vertov's montage theories for their own purposes.

Music

As a silent film from 1925, Kino-Pravda No. 22 was originally exhibited without synchronized sound, which was not yet available in commercial cinema. During its initial Soviet screenings, the film would have been accompanied by live musical performance, typically a pianist or small ensemble playing appropriate music to enhance the emotional and narrative impact. The choice of music would have been left to individual theater musicians, though Soviet guidelines likely suggested revolutionary or folk themes that complemented the film's content. In some cases, the film might have been shown with narration from a lecturer who would explain the images and reinforce the ideological messages. Modern screenings and releases of the film typically feature newly composed scores or period-appropriate classical music that reflects the film's Soviet context. The absence of original synchronized sound means that contemporary viewers experience the film as a purely visual work, which aligns with Vertov's emphasis on the power of images and his belief that cinema should be a universal language that transcends spoken words.

Famous Quotes

'I am the cine-eye. I am a mechanical eye. I, a machine, show you the world as only I can see it.' - Dziga Vertov's manifesto

'The Cine-Eye is a cinema truth, a cinema that is more perfect than the human eye.' - Dziga Vertov

'Lenin lives in the heart of the peasant' - Film's thematic statement

'The kino-eye is a microscope and telescope of time.' - Dziga Vertov

Memorable Scenes

- The departure of the peasant delegation from their rural village, showing traditional life giving way to revolutionary purpose

- The peasants' first arrival in Moscow, capturing their wonder and awe at the Soviet capital

- Scenes of collective mourning at Lenin's memorial, emphasizing the emotional connection between peasants and the revolutionary leader

- Contrasting shots of rural agricultural work and Moscow's industrial development

- The peasants' participation in anniversary ceremonies, showing their integration into Soviet political life

Did You Know?

- This was the 22nd installment in Vertov's Kino-Pravda series, which ran from 1922 to 1925 and comprised approximately 23 issues

- The title 'Kino-Pravda' translates to 'Cinema Truth' or 'Film Truth', reflecting Vertov's documentary philosophy

- Vertov believed that the camera, with its mechanical eye, could perceive truth more accurately than the human eye

- The film was released just one year after Lenin's death on January 21, 1924, during a period of intense Soviet myth-making around the revolutionary leader

- Dziga Vertov's birth name was David Abelevich Kaufman; 'Dziga Vertov' was a pseudonym meaning 'spinning top' in Ukrainian

- The Kino-Pravda series was originally conceived as a weekly newsreel but production irregularities made the schedule inconsistent

- Vertov's wife Elizaveta Svilova was the editor for most of the Kino-Pravda series, including this installment

- The film exemplifies Vertov's theory of 'intervals' - the rhythmic organization of shots through editing to create new meanings

- Many of the peasants featured in the film were likely experiencing their first visit to Moscow, providing authentic reactions to urban Soviet life

- The Kino-Pravda series influenced documentary filmmakers worldwide, including the British Documentary Movement and cinéma vérité practitioners

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet reception of Kino-Pravda No. 22 reflected the complex debates about revolutionary art then occurring in the USSR. Vertov's work was praised by some critics for its innovative techniques and revolutionary spirit, while others criticized it for being too abstract or difficult for mass audiences. Soviet filmmaker and theorist Lev Kuleshov was critical of Vertov's approach, favoring more structured narrative cinema. In the decades following its release, Western critics and film scholars increasingly recognized the importance of Vertov's contributions to cinema language and documentary theory. The film is now considered a classic of documentary cinema and is studied in film schools worldwide as an example of early Soviet montage theory and documentary innovation. Modern critics appreciate the film's historical significance as both a documentary record of early Soviet society and as an influential work in the development of film language. The Kino-Pravda series, including this installment, is now recognized as a crucial precursor to later documentary movements and to reality television formats.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary Soviet audience reception of Kino-Pravda No. 22 was mixed, reflecting the experimental nature of Vertov's approach. While some viewers appreciated the film's innovative techniques and its celebration of Soviet achievements, others found Vertov's rapid montage style and lack of conventional narrative structure confusing. The film's focus on peasants visiting Moscow likely resonated with rural audiences who could identify with the delegates' experiences, while urban viewers gained insight into the lives of their rural compatriots. The subject matter of Lenin's legacy and the peasant-city alliance aligned with official Soviet ideology, making the content acceptable to authorities even as Vertov's methods were sometimes controversial. In subsequent decades, the film has primarily been viewed by film scholars, students, and cinema enthusiasts rather than general audiences, with most modern viewers encountering it in academic or archival contexts. The film's historical significance and innovative techniques are now more appreciated than its immediate entertainment value, as it serves primarily as an important document in the history of cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet revolutionary ideology

- Lenin's writings on cinema

- Futurist art movement

- Constructivist design principles

- Marxist-Leninist theory

- Soviet newspaper journalism

- Vertov's earlier Kino-Pravda installments

This Film Influenced

- Man with a Movie Camera (1929)

- The Man with a Movie Camera

- Three Songs About Lenin (1934)

- British Documentary Movement films

- Cinema vérité documentaries of the 1960s

- Direct Cinema documentaries

- Modern reality television formats

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in several archives including the Russian State Film Archive (Gosfilmofond) and international film institutions. While some deterioration has occurred over the decades, the film remains largely intact and accessible for scholarly study and screening. Digital restorations have been undertaken by various film archives, helping to preserve this important work of early Soviet cinema. The film is part of the larger effort to preserve Vertov's Kino-Pravda series, which represents a crucial chapter in documentary film history. Some original nitrate prints may still exist in specialized archives, though viewing copies are typically made on safer film stock or digital formats for preservation and access purposes.