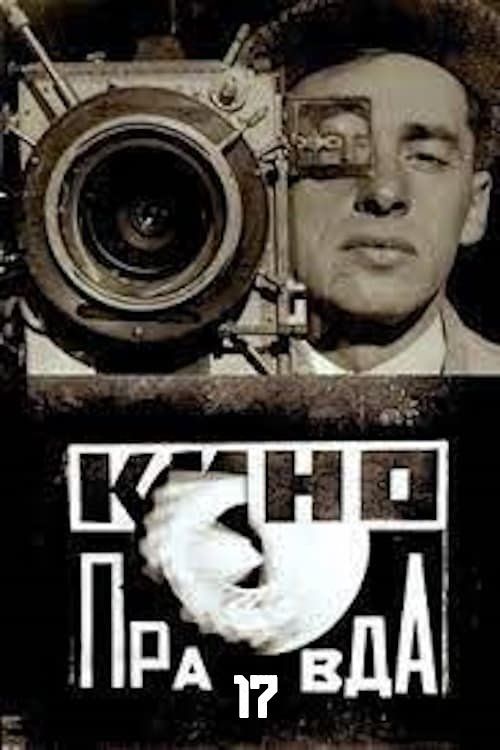

Kino-Pravda No. 17

Plot

Kino-Pravda No. 17 is a Soviet newsreel documentary that captures three distinct aspects of early Soviet society in 1923. The film begins by examining the critical relationship between hunger and harvest, showcasing agricultural efforts to feed the population during a period of recovery. It then explores the developing alliance between urban centers and rural communities, highlighting the cooperative efforts essential to building the new socialist state. The final segment documents an extensive agricultural and home industries exhibition, showing the construction and preparation of the venue, various exhibits including a detailed exhibition map, and the diverse visitors attending this showcase of Soviet productivity and progress.

Director

About the Production

Kino-Pravda No. 17 was part of Dziga Vertov's revolutionary newsreel series that experimented with cinematic language and documentary techniques. The film was shot quickly to maintain timeliness as a newsreel, yet Vertov and his crew employed innovative camera angles, rapid editing, and juxtaposition of images to create meaning beyond simple reportage. The production faced challenges typical of early Soviet cinema including limited film stock, primitive equipment, and difficult shooting conditions in both urban and rural locations during the early post-revolutionary period.

Historical Background

Kino-Pravda No. 17 was produced during a critical period in Soviet history, 1923, when the new communist state was still recovering from the devastating effects of World War I, the Russian Revolution, and the subsequent civil war. The New Economic Policy (NEP) had been introduced in 1921, allowing limited private enterprise while the state maintained control of the 'commanding heights' of the economy. This period saw massive efforts to rebuild agricultural production and industrial capacity, with the alliance between city and countryside being crucial for survival. The agricultural exhibition featured in the film represented Soviet attempts to showcase progress and modernization despite ongoing challenges. Vertov's work was part of the broader avant-garde movement flourishing in early Soviet Russia, where artists were given unprecedented freedom to experiment with new forms that could serve revolutionary purposes. The film reflects the utopian optimism of the period, despite the harsh realities of famine and economic hardship still affecting much of the population.

Why This Film Matters

Kino-Pravda No. 17 represents a pivotal moment in the development of documentary cinema and film language. Vertov's approach revolutionized how documentaries could be made, moving beyond simple recording to create meaning through editing and juxtaposition. The series established principles that would influence generations of documentary filmmakers, from the British Documentary Movement of the 1930s to the cinéma vérité and direct cinema movements of the 1960s. Vertov's theories about the camera as a mechanical eye capable of capturing truth beyond human perception fundamentally challenged conventional filmmaking. The Kino-Pravda series also demonstrated how cinema could serve as a tool for social change and political education, a concept that would be adopted by governments and movements worldwide. The films' innovative editing techniques, rapid cutting, and use of montage expanded the vocabulary of cinema itself, influencing not just documentary but also experimental and narrative filmmaking.

Making Of

The production of Kino-Pravda No. 17 exemplified Vertov's radical approach to documentary filmmaking. Working with his brother Mikhail Kaufman and wife Elizaveta Svilova (who edited), Vertov rejected traditional narrative cinema in favor of what he called 'the perfect synthesis of newsreel, document, and art.' The crew traveled extensively throughout Soviet Russia, often working with primitive equipment and dangerous conditions to capture authentic footage. Vertov insisted on filming people in their natural environments without their knowledge, believing this captured the truth of Soviet life. The editing process was particularly innovative, with Svilova assembling disparate shots to create new meanings and ideological messages through montage. The team faced constant pressure from Soviet authorities to produce films that served the revolutionary cause while maintaining their artistic integrity and experimental approach.

Visual Style

The cinematography in Kino-Pravda No. 17 exemplifies Vertov's revolutionary approach to documentary photography. Mikhail Kaufman employed innovative camera techniques including extreme close-ups, Dutch angles, low and high angles, and tracking shots to create dynamic visual interest. The camera often captured subjects from unexpected perspectives, reflecting Vertov's belief in the superiority of the mechanical eye over human vision. Kaufman utilized handheld cameras to achieve mobility and spontaneity, allowing for intimate coverage of both urban and rural environments. The exhibition sequences feature sweeping shots that establish scale and detail shots that highlight specific exhibits and visitors. The cinematography emphasizes movement and energy, with frequent camera motion and dynamic framing that create a sense of vitality and progress. Visual contrasts between industrial and agricultural settings reinforce the film's themes of urban-rural alliance.

Innovations

Kino-Pravda No. 17 demonstrated several technical innovations that advanced documentary filmmaking. Vertov and his team pioneered portable camera techniques that allowed for greater mobility and spontaneity in capturing real events. The film's editing employed rapid montage techniques that were revolutionary for their time, creating meaning through the collision of images rather than through traditional narrative continuity. The production utilized multiple camera coverage of events, allowing for more dynamic editing possibilities. Vertov experimented with superimposition, split screens, and other optical effects to create visual metaphors and ideological connections. The series developed what Vertov called 'intervala shooting' - capturing the intervals between movements rather than just the movements themselves. These technical innovations expanded the vocabulary of cinema and established new possibilities for documentary expression that would influence filmmakers for decades.

Music

As a silent film from 1923, Kino-Pravda No. 17 was originally exhibited without synchronized sound. In Soviet theaters, it would have been accompanied by live musical performance, typically piano or small ensemble, with music selected or improvised to match the on-screen action and mood. The choice of music could significantly influence audience interpretation of the images, with upbeat music for progress scenes and more somber tones for segments about hunger. Some Soviet cinemas employed explanatory narration or intertitles read aloud during screenings to provide additional context. Modern restorations and screenings often feature newly composed scores by contemporary musicians, ranging from traditional piano accompaniment to experimental electronic music that reflects Vertov's avant-garde sensibilities. The absence of synchronized sound actually enhanced Vertov's focus on visual storytelling and the power of images to convey meaning without dialogue.

Famous Quotes

'I am the mechanical eye. I, the machine, show you the world as only I can see it.' - Dziga Vertov's Kino-Eye manifesto

'Kino-Pravda means the filming of life unawares.' - Dziga Vertov

'We cannot improve the making of eyes, but we can perfect the mechanical eye.' - Dziga Vertov

'The camera is a machine that cannot lie.' - Dziga Vertov

'I am kino-eye, I am a mechanical eye.' - Dziga Vertov

Memorable Scenes

- The exhibition construction sequence showing workers building the venue, emphasizing Soviet collective labor and progress

- The sweeping shots of the agricultural exhibition grounds with crowds of visitors, showcasing the scale and importance of the event

- The juxtaposition of urban and rural scenes highlighting the alliance between city and countryside

- The close-up shots of agricultural machinery and implements, symbolizing Soviet modernization efforts

- The montage sequence connecting hunger, harvest, and exhibition to create ideological meaning

Did You Know?

- Kino-Pravda No. 17 is part of a series of 23 newsreels made between 1922-1925, with 'Kino-Pravda' translating to 'Cinema Truth' in English

- The series pioneered what Vertov called 'life caught unawares' - capturing authentic moments without staging or intervention

- Vertov's brother Mikhail Kaufman was the principal cinematographer for many Kino-Pravda installments

- The agricultural exhibition featured in this film was likely the First All-Russian Agricultural and Handicraft Industrial Exhibition held in Moscow in 1923

- Kino-Pravda films were typically shown before feature films in Soviet cinemas as newsreels

- Vertov believed the camera eye was superior to human vision, capable of seeing and recording truth more objectively

- The series influenced documentary filmmakers worldwide, including the British Documentary Movement and cinéma vérité practitioners

- Each Kino-Pravda installment was numbered sequentially, with No. 17 representing the 17th in the series

- The films were edited to create ideological meaning through the juxtaposition of images, a technique Vertov called 'intellectual cinema'

- Despite their newsreel format, Kino-Pravda films were carefully constructed artistic works, not simple recordings of events

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics generally praised the Kino-Pravda series for its innovative approach and ideological clarity, though some found Vertov's experiments too radical. The films were recognized as important contributions to developing a distinctly Soviet cinema that rejected bourgeois traditions. International critics were slower to appreciate Vertov's work, with many Western reviewers finding the films chaotic or propagandistic. However, avant-garde filmmakers and theorists in Europe recognized the significance of Vertov's innovations. Modern critics and film scholars now regard Kino-Pravda No. 17 and the entire series as landmarks in documentary history, praising their formal innovation and influence despite acknowledging their propagandistic elements. The films are studied in film schools worldwide as examples of early documentary technique and cinematic experimentation.

What Audiences Thought

Soviet audiences in 1923 received Kino-Pravda newsreels as part of regular cinema programs, where they served both as news sources and ideological reinforcement. The films were generally popular for showing familiar aspects of Soviet life and progress, though their experimental style sometimes confused viewers accustomed to more traditional cinema. The agricultural exhibition footage likely resonated particularly well with audiences interested in Soviet development and modernization efforts. International audiences had limited exposure to the films during Vertov's lifetime, as they were primarily distributed within the Soviet Union. Modern audiences encountering the films through retrospectives and academic screenings often find them challenging but rewarding, requiring adjustment to their rapid pace and non-narrative structure. The films are now primarily viewed by cinema enthusiasts, students, and scholars rather than general audiences.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet constructivist art

- Futurism

- Theories of Marxist dialectics

- Earlier documentary traditions

- Avant-garde photography

- Soviet newspaper journalism

This Film Influenced

- Man with a Movie Camera (1929)

- The Man with a Movie Camera

- British Documentary Movement films

- Cinema vérité documentaries

- Direct cinema works

- Lenin with a Bottle of Vodka (1924)

- Stride, Soviet! (1926)

- The Eleventh Year (1928)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Kino-Pravda No. 17 survives in archives and has been preserved as part of the important legacy of early Soviet cinema. The film exists in various film archives including the Gosfilmofond in Russia and international collections. Some versions show signs of deterioration typical of nitrate film from the era, but preservation efforts have maintained the film's accessibility. The film has been included in DVD collections and digital archives dedicated to Vertov's work and early documentary cinema. While not as widely available as Vertov's more famous feature films like 'Man with a Movie Camera,' dedicated cinema archives and specialized distributors ensure that this important installment of the Kino-Pravda series remains accessible to scholars and enthusiasts of film history.