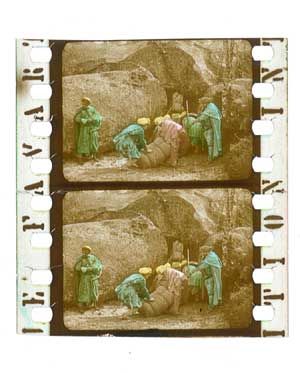

Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves

Plot

In this early cinematic adaptation of the classic Arabian tale, poor woodcutter Ali Baba accidentally discovers the secret hideout of forty thieves and their vast treasure, accessed by the magical phrase 'Open Sesame.' His greedy brother Cassim learns of the cave and enters, but forgets the exit password and is trapped, leading to his brutal murder by the returning thieves. The thieves soon realize their secret has been exposed and devise a cunning plan to eliminate Ali Baba and anyone else who might know their hiding place, leading to a series of deadly encounters and clever tricks. Ali Baba must rely on his wits and the help of his faithful servant Morgiana to survive the thieves' vengeance and protect the treasure. The film culminates in a dramatic confrontation where good triumphs over evil through intelligence and loyalty.

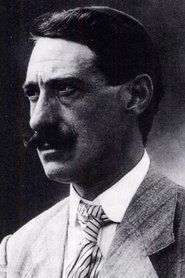

Director

About the Production

This film was created using Pathécolor stencil coloring process, one of the earliest color film techniques. Segundo de Chomón employed multiple exposure techniques and substitution splices to create magical effects. The film featured elaborate painted backdrops and props typical of the féerie genre popularized by Georges Méliès. The production required careful coordination of actors and special effects, as many scenes involved disappearances and magical transformations that had to be captured in-camera.

Historical Background

1907 was a pivotal year in early cinema, marking the transition from simple actualities to narrative storytelling. The film industry was rapidly consolidating, with companies like Pathé establishing global dominance. This period saw the emergence of specialized genres, with fantasy and féerie films being particularly popular. The technical innovations in special effects and color processes represented the cutting edge of film technology. European cinema, particularly French, was leading the world in film production and artistic innovation. The adaptation of literary classics like Arabian Nights reflected cinema's growing ambition to be taken seriously as an art form capable of adapting established literary works.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents an important early example of cross-cultural storytelling in cinema, bringing an Arabian tale to European audiences. It helped establish the fantasy genre as a viable commercial category in early film. The film's visual style influenced how Oriental stories would be presented in Western cinema for decades. As one of de Chomón's major works, it contributed to establishing special effects as an essential element of fantasy filmmaking. The adaptation demonstrates how early cinema served to popularize and visualize stories that were previously only known through books and oral traditions. It also exemplifies the early 20th century European fascination with the Orient, a theme that would recur throughout cinema history.

Making Of

Segundo de Chomón created this film during his peak period at Pathé Frères, where he was head of special effects. The production involved complex in-camera effects including multiple exposures, substitution splices, and careful timing to achieve the magical elements. The actors had to perform in highly stylized manner typical of early cinema, with exaggerated gestures to convey emotion without dialogue. The elaborate costumes were designed to evoke European fantasies of the Orient rather than authentic Middle Eastern dress. The cave scenes were filmed using forced perspective and carefully painted backdrops to create the illusion of vast underground chambers. De Chomón personally supervised the hand-coloring process, which required hundreds of workers applying colors frame by frame using stencils.

Visual Style

The cinematography employed static camera positions typical of early cinema, allowing the focus to remain on the staged effects and performances. The film utilized multiple exposure techniques to create ghostly appearances and magical transformations. Careful lighting was employed to enhance the hand-colored effects and create dramatic shadows in the cave scenes. The cinematography emphasized spectacle over realism, with bright colors and theatrical compositions. The camera work was designed to showcase the special effects rather than create immersion, reflecting the theatrical origins of early film presentation.

Innovations

Pioneered the use of Pathécolor stencil coloring process for narrative films. Developed sophisticated multiple exposure techniques for magical effects. Created elaborate substitution splices for transformation scenes. Utilized forced perspective and painted backdrops to create convincing fantasy environments. Demonstrated early mastery of in-camera special effects that would influence future fantasy filmmakers. The film represents an early successful integration of color technology with narrative storytelling, showing how technical innovation could enhance dramatic effect rather than merely serve as novelty.

Music

As a silent film, it would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters. The typical accompaniment would have included popular classical pieces, theater music, or improvised piano accompaniment. The music would have been synchronized to match the dramatic moments, with faster tempos for action sequences and slower melodies for emotional scenes. Some theaters might have used cue sheets provided by Pathé suggesting appropriate musical pieces. The exotic setting would have inspired the use of 'Oriental' sounding music popular in the early 20th century.

Famous Quotes

'Open Sesame' - the magical phrase to open the thieves' cave

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic moment when Ali Baba first discovers the thieves' cave and witnesses the magical opening with 'Open Sesame', the elaborate entrance of the forty thieves on horseback with their stolen treasures, the terrifying scene of Cassim being trapped in the cave when he cannot remember the exit phrase, the clever sequence where Morgiana discovers the thieves hiding in oil jars and defeats them one by one, the final confrontation where Ali Baba outwits the remaining thieves through cunning rather than force

Did You Know?

- Segundo de Chomón was often called the 'Spanish Méliès' due to his similar style of fantasy films and special effects innovations

- The film used the stencil coloring process where each frame was hand-colored by applying stencils and dyes individually

- This was one of the earliest film adaptations of the Ali Baba story, predating many more famous versions

- De Chomón worked as a colorist for Pathé before becoming a director, giving him expertise in early color techniques

- The 'Open Sesame' magical phrase was already well-known in Western culture by 1907 through translations of Arabian Nights

- The film featured elaborate costumes and sets that were typical of the exoticism popular in early 20th century European cinema

- Many of de Chomón's films were distributed internationally, making him one of the first globally recognized film directors

- The thieves' cave was created using painted backdrops and perspective tricks to create depth in the limited studio space

- This film was part of a series of fairy tale and fantasy adaptations that Pathé produced in the 1900s

- The original print included intertitles in French, with versions later created for international distribution

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in trade publications praised the film's visual effects and coloring, with Moving Picture World noting its 'splendid effects and beautiful coloring.' French film journals highlighted de Chomón's technical wizardry and compared him favorably to Méliès. Modern film historians recognize the work as an important example of early fantasy cinema and de Chomón's technical prowess. Critics today appreciate the film as a document of early cinematic techniques and as an example of how exotic tales were adapted for early film audiences. The film is studied for its pioneering use of color and special effects in the pre-feature film era.

What Audiences Thought

The film was commercially successful in its initial release, particularly in European markets where fantasy films were popular. Audiences were amazed by the color effects and magical transformations, which were still novel in 1907. The exotic setting and familiar story appealed to audiences who knew the Arabian Nights tales. The film's relatively short runtime made it suitable for variety-style theater programs that were common at the time. Contemporary audience reports suggest the film was particularly popular with family audiences and children. The visual spectacle of the film helped establish Pathé's reputation for high-quality productions.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Georges Méliès' fantasy films

- Arabian Nights stories

- European féerie theater tradition

- Pathé's established fantasy film formula

This Film Influenced

- Later adaptations of Ali Baba stories

- Fantasy films of the 1910s and 1920s

- Adventure films with treasure themes

- Douglas Fairbanks' The Thief of Bagdad (1924)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in archives, with prints held at the Cinémathèque Française and other film archives. Some versions retain the original hand-coloring, while others exist as black and white prints. The film has been restored and included in various DVD collections of early cinema and Segundo de Chomón's works. The survival of this 1907 film is remarkable given the high loss rate of early cinema.