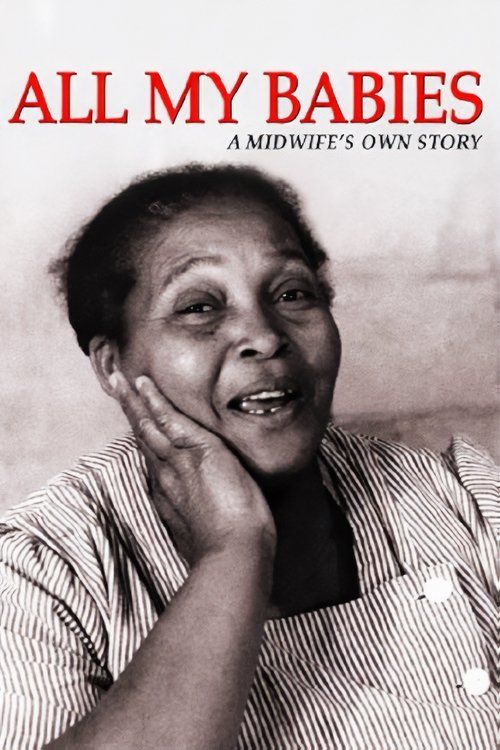

All My Babies... A Midwife's Own Story

Plot

This landmark documentary follows Mary Francis Hill Coley, an African-American midwife in rural Georgia, as she provides essential healthcare to Black communities in the segregated South. The film captures Coley attending to pregnant women, delivering babies, and sharing her extensive knowledge with younger midwives, showcasing both traditional practices and modern medical techniques. Through intimate scenes of actual births and Coley's interactions with families, the documentary reveals the crucial role midwives played in areas where doctors were scarce or unwilling to serve Black patients. The film presents a compassionate portrait of community-based healthcare while addressing broader issues of racial segregation, healthcare disparities, and the preservation of traditional knowledge in mid-20th century America.

Director

About the Production

Director George C. Stoney spent several months living with Mary Coley and her community before filming to build trust and capture authentic moments. The film was commissioned specifically to train midwives in Georgia but gained wider recognition for its humanistic approach. The crew used lightweight cameras to film in cramped home conditions during actual births, requiring technical innovation for the time. Stoney insisted on filming real deliveries rather than reenactments, making this one of the first documentaries to show childbirth on screen.

Historical Background

This film was created during the early years of the Civil Rights Movement, just before the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision in 1954. The American South was still deeply segregated, and African Americans, especially in rural areas, had severely limited access to healthcare. Midwives like Mary Coley were essential to the survival of Black communities, providing not just medical care but also emotional support and cultural continuity. The film was made during a period when the public health establishment was trying to professionalize midwifery while still acknowledging the importance of traditional knowledge. This was also a time when documentary filmmaking was evolving from purely educational or propagandistic purposes to more humanistic approaches that valued the authentic voices of subjects. The film captures a pivotal moment when traditional African-American practices were being documented just as they were beginning to disappear.

Why This Film Matters

All My Babies represents a crucial bridge between traditional African-American midwifery practices and modern medical approaches, documenting a profession that was both essential to community survival and under threat from medical professionalization. The film is significant for its respectful portrayal of African-American life at a time when such representations were rare in American cinema. It preserves an important aspect of Black women's history and the history of healthcare in America. The documentary also stands as an early example of what would later be called cinema verité or observational documentary, influencing generations of filmmakers. Its selection for the National Film Registry recognizes its importance not just as a medical training film but as a work of historical and cultural significance that provides insight into the resilience and expertise of African-American women in the rural South.

Making Of

George C. Stoney approached this project with extraordinary sensitivity, spending months immersed in the community before filming began. He worked with a minimal crew to avoid disrupting the natural flow of life and medical procedures. The filming required navigating the complex social dynamics of the segregated South while maintaining the dignity and autonomy of the subjects. Stoney developed a deep friendship with Mary Coley, which allowed for unprecedented access to intimate moments including actual births. The crew faced technical challenges filming in rural homes with limited electricity and space, often working in cramped conditions with specialized portable equipment. Stoney's decision to let events unfold naturally rather than scripting scenes was revolutionary for documentary filmmaking in the 1950s and influenced generations of filmmakers. The production team had to balance the educational requirements of the health department commission with their artistic vision, ultimately creating a work that transcended its original purpose.

Visual Style

The black and white cinematography creates a stark, honest quality that enhances the documentary feel while maintaining the clinical clarity needed for a training film. The camera work is steady and observant, allowing scenes to unfold naturally without interference. The lighting in the birth scenes is particularly notable for creating visibility without disrupting the medical environment, often using available light supplemented minimally to maintain authenticity. The cinematography manages to be both educational and deeply human, finding beauty in everyday moments while capturing the technical aspects of medical procedures. The visual style emphasizes the textures of rural life and the intimate spaces where Coley worked, creating a sense of immediacy and presence that was innovative for documentary filmmaking in the 1950s.

Innovations

The film was technically innovative for its use of lightweight cameras that could move more freely in tight spaces, allowing for more intimate filming of medical procedures. The audio recording techniques used to capture clear dialogue and natural sounds in rural settings were advanced for the period. The film's editing structure, which follows the natural timeline of pregnancies and births, was revolutionary in its avoidance of artificial dramatic structure. The successful capture of actual birth scenes on film was a significant technical achievement that required specialized equipment and techniques. The production team developed new methods for filming in low-light conditions without disrupting medical procedures, innovations that would later influence documentary filmmaking practices.

Music

The film uses minimal music, relying primarily on natural sounds and ambient audio to create authenticity. When music is used, it's typically traditional African-American spirituals or folk songs that reflect the cultural context of the community. The soundtrack emphasizes the sounds of the rural environment and the voices of the people, particularly Coley's gentle instructions and conversations with the mothers. The natural sound approach was innovative for its time, predating the cinema verité movement's emphasis on authentic audio. The careful attention to sound recording allows viewers to hear not just dialogue but the subtle sounds of medical work, home environments, and community life, adding layers of meaning to the visual documentation.

Famous Quotes

They're all my babies. Every one of them. - Mary Francis Hill Coley

When you bring a baby into the world, you bring a new soul to God. - Mary Coley

The Lord gave me these hands to help bring his children into the world. - Mary Coley

A midwife must know more than just how to catch a baby. She must know how to comfort a mother. - Mary Coley

In this work, you can't be afraid. You have to have faith. - Mary Coley

Memorable Scenes

- The scene where Mary Coley delivers twins in a small rural home, demonstrating her calm expertise under challenging conditions

- The sequence showing Coley teaching younger midwives proper techniques, highlighting the importance of knowledge transfer

- The intimate moments between Coley and expectant mothers, showing the emotional support she provided beyond medical care

- The scenes of Coley traveling between homes on foot or by horseback, illustrating the dedication required for her work

- The final sequence showing a healthy baby being presented to the family, capturing the joy and relief of successful childbirth

Did You Know?

- Selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 2002 for being 'culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant'

- Mary Francis Hill Coley delivered over 3,000 babies during her 30+ year career as a midwife

- The film was one of the first to show actual births on screen, which was groundbreaking for its time

- Director George C. Stoney was later known as the 'father of public access television'

- Despite being commissioned as a training film, it won first prize at the Edinburgh Film Festival in 1956

- The film was used not only in Georgia but was distributed to health departments across the United States and internationally

- In 1999, the film was restored by the National Film Preservation Foundation

- The documentary captures actual conversations and interactions, not staged scenes, making it an important ethnographic document

- The title comes from Coley's own words about the babies she delivered: 'They're all my babies'

- The film was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature in 1953

What Critics Said

Upon its release, the film was praised for its educational value and its sensitive handling of its subject matter. Critics noted its effectiveness as a training tool while also appreciating its artistic qualities. The New York Times highlighted its 'warmth and humanity' in portraying Coley's work. Over time, the film has gained recognition as a landmark documentary, with modern critics praising its observational style and historical importance. Film scholars consider it a precursor to the direct cinema movement of the 1960s. Contemporary critics have noted how the film transcends its educational purpose to become a profound meditation on community, tradition, and the dignity of labor. The documentary is now studied in film schools, public health programs, and African-American studies courses for its multidimensional significance.

What Audiences Thought

As an educational film, All My Babies was primarily shown to health professionals and midwives in training, where it was well-received for its practical value and respectful approach. When it was later screened in film festivals and theaters, audiences were moved by the authentic portrayal of Coley's work and the intimate look at life in the rural South. Contemporary audiences viewing the restored version often express appreciation for the window it provides into a rarely documented aspect of American history and the dignity with which it treats its subjects. The film has developed a cult following among documentary enthusiasts and those interested in the history of midwifery and African-American healthcare traditions.

Awards & Recognition

- Selected for preservation in the National Film Registry (2002)

- First prize at the Edinburgh Film Festival (1956)

- Robert J. Flaherty Award for best documentary (1953)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- British documentary movement of the 1930s-40s

- John Grierson's social documentary approach

- Robert Flaherty's ethnographic filmmaking

- Public health education films

- Medical documentary tradition

This Film Influenced

- The Salesman (1969)

- Hospital (1970)

- High School (1968)

- Grey Gardens (1975)

- The Midwife's Mother (2014)

- Birth Story: Ina May Gaskin and The Farm Midwives (2012)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry in 2002. It was restored by the National Film Preservation Foundation in 1999. Original 35mm prints are held in several archives including the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art's film collection. The restored version is available in digital format and has been preserved for future generations.