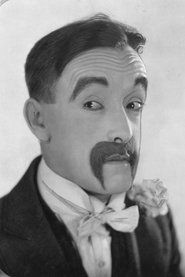

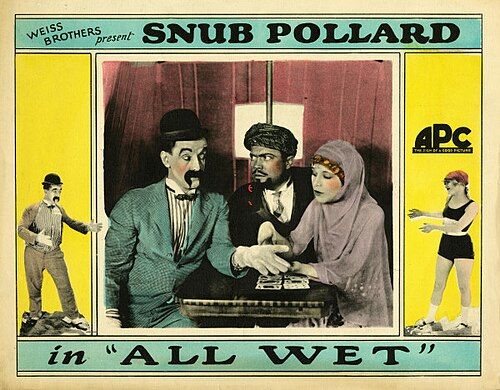

All Wet

Plot

Harry 'Snub' Pollard plays a naive young man who leaves his tiny hometown to live with his wealthy aunt, whom he's never met. Upon arriving at her mansion during a lavish party, his aunt initially refuses him entry until discovering he owns an oil well, after which she warmly welcomes him. She desperately tries to push him toward her vampish daughter, but Snub finds himself drawn instead to the family's sweet maid. Despite his clear preference for the maid, the family's relentless pressure eventually leads Snub to agree to marry the cousin, prompting the clever maid to devise a plan exposing the family's gold-digging scheme, which culminates in a classic silent comedy chase sequence.

Director

James D. DavisCast

About the Production

Filmed during the height of the silent comedy era when two-reel shorts were a staple of movie theater programming. The film was likely shot quickly over 2-3 days, which was standard for comedy shorts of this budget level. The oil well prop and mansion setting suggest the production had access to decent resources for a Weiss Brothers production.

Historical Background

1926 was a pivotal year in cinema history, representing the peak of the silent era just before the transition to sound began with 'The Jazz Singer' in 1927. The film industry was dominated by comedy shorts as essential programming for theaters, with stars like Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton, and Charlie Chaplin at their height. The economic boom of the Roaring Twenties created audiences hungry for entertainment, and films like 'All Wet' reflected contemporary themes of sudden wealth and social climbing. The oil industry was particularly prominent in California culture during this period, with discoveries like Signal Hill creating overnight millionaires and capturing the public's fascination with rags-to-riches stories.

Why This Film Matters

While not a groundbreaking work, 'All Wet' represents the typical comedy short that formed the backbone of silent-era cinema programming. The film's themes of class conflict, genuine love versus materialism, and the triumph of the common man resonated with 1920s audiences experiencing rapid social changes. The oil well subplot reflects the era's get-rich-quick mentality and the American Dream's darker side of opportunism. As a product of the Weiss Brothers studio, it exemplifies the type of content that served smaller theaters and working-class audiences, complementing the more polished productions from major studios.

Making Of

The production of 'All Wet' followed the typical rapid-fire schedule of silent comedy shorts. Director James D. Davis, a veteran of comedy filmmaking, would have worked closely with Snub Pollard to develop gags and timing. The mansion setting was likely rented from one of the many production houses that offered standing sets to smaller studios. The oil well prop would have been a significant expense for a Weiss Brothers production, suggesting they had confidence in the film's commercial potential. The chase sequence at the film's climax would have been carefully choreographed and likely filmed in one day to maximize efficiency. Pollard, known for his willingness to perform his own stunts despite his small stature, would have been extensively involved in planning the physical comedy elements.

Visual Style

The cinematography would have been straightforward and functional, typical of comedy shorts of the era. The camera work would emphasize clarity for gags and chase sequences rather than artistic flourishes. Interior shots in the mansion would use basic three-point lighting to ensure visibility, while exterior scenes would rely on natural light. The camera would remain relatively static during dialogue sequences (conveyed through intertitles) but become more mobile during chase scenes, using tracking shots to follow the action. The visual style would prioritize comedic timing and clear storytelling over innovation.

Innovations

As a modest comedy short, 'All Wet' would not have featured significant technical innovations. The film would have been shot on standard 35mm film with typical cameras of the period. Any special effects would have been practical and in-camera, such as the oil well prop and basic stunt work. The technical aspects would have focused on reliability and efficiency rather than pushing boundaries, reflecting the practical needs of high-volume short film production.

Music

As a silent film, 'All Wet' would have been accompanied by live music during theatrical screenings. The theater's organist or pianist would have improvised or used stock music appropriate to the mood of each scene - upbeat tunes for comedic moments, romantic themes for the maid scenes, and frantic music during the chase sequence. Some theaters might have used cue sheets provided by the distributor suggesting specific musical pieces. No original composed score would have existed for a production of this scale.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, dialogue was conveyed through intertitles rather than spoken quotes

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic chase sequence where the maid exposes the family's deception, featuring Snub Pollard's character in frantic pursuit through the mansion and grounds, utilizing classic silent comedy physical gags and timing

Did You Know?

- Harry 'Snub' Pollard was born Harry Pollard in Australia and moved to the United States as a child, beginning his film career in 1915

- The film was released by Weiss Brothers-Artclass Pictures, a studio that specialized in low-budget comedy shorts during the silent era

- Director James D. Davis directed over 200 films between 1915 and 1938, mostly comedy shorts

- The title 'All Wet' was a common phrase in the 1920s meaning 'completely mistaken' or 'wrong', fitting the film's theme of mistaken intentions

- Snub Pollard's character type - the diminutive, naive everyman - was popular in silent comedies as an underdog audiences could root for

- The oil well plot element reflected the 1920s oil boom in California, which was creating new millionaires and capturing public imagination

- Weiss Brothers productions were often distributed to smaller theaters and rural areas, making them less likely to survive in archives

- The film was part of a series of Snub Pollard comedies produced by Weiss Brothers in 1926

- Silent comedy shorts like this typically served as supporting features before main attractions in movie theaters

- The maid character was a common trope in silent comedies, often representing the 'real' person versus the artificial upper class

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of comedy shorts like 'All Wet' were rarely preserved in major publications, as they were considered secondary programming. Trade publications like Variety and Moving Picture World likely gave it brief mentions, focusing on its entertainment value rather than artistic merit. Modern film historians view such works as important artifacts of silent comedy techniques and 1920s popular culture, though they rarely receive individual critical attention unless they feature major stars or represent significant technical innovations.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1926 would have received 'All Wet' as light entertainment before or between feature presentations. The film's formulaic plot of mistaken identity, class commentary, and physical comedy would have been familiar and comforting to regular moviegoers. Snub Pollard, while not a top-tier star like Chaplin or Keaton, had a dedicated following among audiences who enjoyed his underdog characters. The film's success would have been measured by its ability to satisfy theater programmers and keep audiences entertained rather than by critical acclaim or box office records.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The typical structure of Mack Sennett comedies

- Harold Lloyd's 'everyman' character type

- Standard silent comedy chase sequences pioneered by Keystone Studios

- The rich-versus-poor theme common in 1920s comedies

This Film Influenced

- The film follows established comedy conventions rather than introducing new ones

- Similar two-reel comedies by other studios would have used comparable plot structures

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of 'All Wet' (1926) is uncertain. Many Weiss Brothers productions from this era have been lost due to the unstable nitrate film stock used in the 1920s and the lack of systematic preservation efforts for smaller studio productions. Some Snub Pollard shorts have survived in archives or private collections, but the specific survival status of this title would need verification from film archives such as the Library of Congress, UCLA Film & Television Archive, or the Museum of Modern Art's film collection.